Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

Eardley 100

By Jan Patience, 25.08.2021

Major anniversaries have a habit of creeping up unbidden but, used wisely, they provide an opportunity to highlight, reconsider and discover more about an artist's life; playing to a gallery of existing and yet-to-be discovered fans. So it has proved with the centenary of the birth of the painter Joan Eardley, whose legacy we are in the midst of marking this year.

Joan Eardley is, and always has been, an artist's artist. Her standing among fellow artists and arts professionals has remained almost reverential since her death, aged 42, in 1963. The year after she died, Cordelia Oliver, artist, critic and contemporary from the Glasgow School of Art (GSA), wrote that her friend ‘painted her surroundings bone-deep’. Oliver would go on to document that feeling of raw connection in greater depth in her 1988 biography of Eardley.

As a result of this ongoing love affair, 'Eardley 100' has developed into a hive-like happening like no other. I like to think that hard-grafting Joan, no fan of glitz and glamour, would have enjoyed the fact her family has joined forces with a group of influential women working behind the scenes in museums, galleries, archives, educational institutions and heritage organisations to create a centenary programme which is reaching out beyond the glittering salons.

Traditionally, in the lead-up to the centenary of such a popular and influential artist as Eardley, a retrospective might have been planned. Timing is everything in the art world, however, and in Eardley's case, the National Galleries of Scotland had already held two major exhibitions of her work in Edinburgh; a retrospective in 2007 and A Sense of Place in 2016–17, which focused on drawings and paintings made in Townhead, Glasgow, and at Catterline on Scotland's north-east coast.

This year could have offered a stage for a major centenary exhibition in her adopted home city of Glasgow or even in London, where she lived from the age of five to 18. It was certainly an ambition of Eardley's artist niece, Anne Morrison-Hudson, who looks after the Eardley Estate. For various reasons, this did not happen.

Joan Eardley, Flood Tide, 1962. Photograph courtesy of the Lillie Art Gallery. Ⓒ Joan Eardley Estate.

Joan Eardley, Flood Tide, 1962. Photograph courtesy of the Lillie Art Gallery. Ⓒ Joan Eardley Estate.

In April 2020, as the world headed into lockdown, it looked like her centenary year would pass unmarked. As the weeks went on, communications started to whirr in the ether between a newly formed group called the Scottish Women in the Arts Research Network (SWARN) and the Eardley Estate.

As a journalist who covers the Scottish art scene for The Herald newspaper, I had already had conversations with Anne Morrison-Hudson and other influential commentators about how to mark her legacy. Realising no major exhibition was going to happen, Anne and I hatched a plan to set up an official website and attendant social media. This was under construction when we were invited to join a Zoom meeting hosted by SWARN.

Special mention for the creation of this can-do group must go to Dr Patricia de Montfort of the University of Glasgow's School of Culture and Creative Arts, and her curator colleague, Anne Dulau, who have worked tirelessly to bring together a raft of professionals committed to enhancing the visibility in public collections of female creatives in fine arts, design, craft and architecture.

Over the course of several months, as our lockdown locks grew ever-longer, the group behind SWARN grew in line with various plans from a growing roster of members looking to celebrate Eardley in her centenary year. What a joy it was to hear from the likes of Jenny Brownrigg and Susannah Thompson about their research into Eardley's time at GSA. These findings would, all being well, morph into an exhibition at the art school in late 2021.

And then there was the revelation from Paisley Museum and Art Galleries curator Victoria Irvine that they had in their collection, among other Eardley works, a playpen made and designed by Eardley around the time she worked as a joiner's labourer after leaving art school in 1943. It had been gifted to Paisley in the 1990s.

Joanna Meacock, curator of British Art at Glasgow Museums, gave an inspiring presentation about plans to present a digital ‘festival’ around the 24 Eardley artworks in its collection. The Hunterian's planned exhibition for summer 2021, we discovered, would be focusing on 20 or so works, including the stand-out Salmon Nets and Sea (1960) and Sweetshop, Rotten Row (1957–61), gifted by the poet Edwin Morgan after his death in 2010.

In the summer of 2020, the official Joan Eardley website, created by artist and curator, Lynne Mackenzie, went live. The biography and timeline which I had written was swiftly joined by news of events and exhibitions from Aberdeen to Dumfries from SWARN members, all under the banner of #Eardley100.

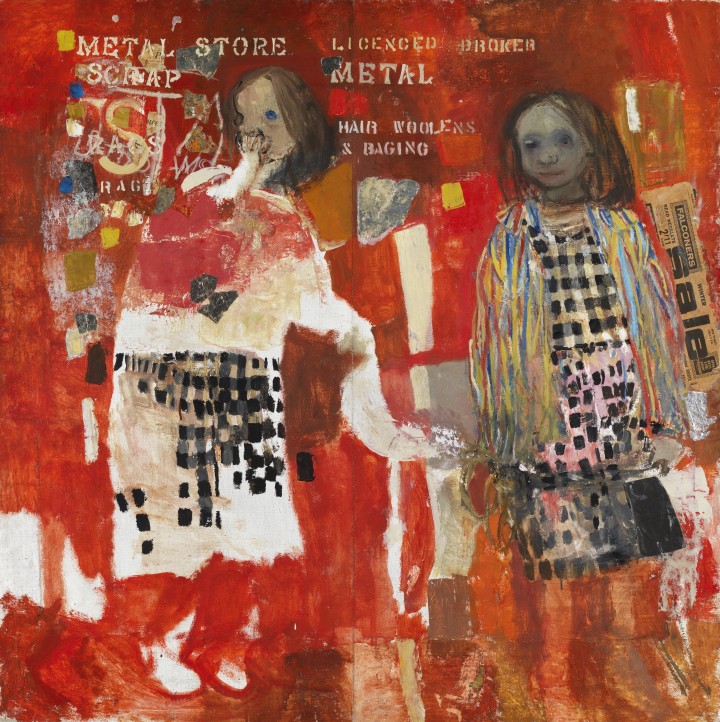

Joan Eardley, Sweet Shop, Rotten Row, 1960 - 1961. Ⓒ Joan Eardley Estate.

Joan Eardley, Sweet Shop, Rotten Row, 1960 - 1961. Ⓒ Joan Eardley Estate.

To date, we have witnessed several online seminars celebrating Eardley's life and legacy, which can be viewed on the website. A highlight was a celebration on 18 May, Eardley's birthday, organised by the Hunterian. Over 500 people joined the webinar from across the world for what proved to be a sparkling event chaired with elan by BBC Scotland's arts correspondent, Pauline McLean.

Leila Riszko, a curatorial assistant with the National Galleries of Scotland, who has worked on its latest Joan Eardley display, Eardley and Catterline, talked to art historian Matilda Hall about the gargantuan task of cataloguing 650 drawings in the early 1980s on behalf of the family. Matilda, who went on to marry Douglas Hall, first Keeper of the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art – and a true champion of Eardley – told the audience about taking the drawings out from a box under Joan's sister Pat's sofa and working her way through them. ‘Every piece of paper became a jewel in my hand,’ Matilda said.

Most of the drawings were distributed to galleries. Over 200 went to the National Gallery of Scotland's collection while other institutions such as the GSA, the family's local gallery, the Lillie in Milngavie, Aberdeen Art Gallery, Glasgow Museums and the Hunterian all received gifts. Matilda revealed she even wrote to the National Art Gallery of New Zealand to offer them a drawing as it had a Catterline seascape in its collection, but they said ‘no’.

A handful of drawings were kept back by the family and marked for sale. Over the years, trusted dealers, such as the late Cyril Gerber from Glasgow's Compass Gallery and the Scottish Gallery, would come and have a look and take some away for sale. Some of these works, such as Mrs Red Wallpaper, which Joan made in either Italy or Arran, remain in private collections. Take a look at the event, which is on the Eardley website – maybe someone out there reading this has one of these drawings.

The genius of Joan Eardley touches people at their core. Monitoring the Joan Eardley social media, I can see that interest in her work is at an all-time high and I couldn't be more delighted. Here's to Joan Eardley at 100, 150 and 200. She is now, as Edwin Morgan put it so perfectly in his poem inspired by her Flood Tide painting, ‘beyond the sun’.

Jan Patience is an arts journalist and co-organiser of the Joan Eardley centenary. For more information, check out JoanEardley.com and SWARN.