Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

William Gillies, an unrecognised modernist?

By Susan Mansfield, 09.02.2024

William Gillies occupies an important place in 20th-century Scottish art as a painter, particularly of landscape, and a teacher, over many years, at Edinburgh College of Art. But if one had to list the leading proponents of modernism, he wouldn’t be the first to spring to mind.

A new book by Andrew McPherson, William Gillies: Modernism and Nation in British Art, demonstrates, for the first time, the depth and importance of his engagement with modernism, arguing he is “an unrecognised part of the story of modernism in Britain”. A parallel exhibition mounted by the RSA will tour Scotland until December 2025, casting a new light on Gillies, his work and his life.

Examples of Gillies’ modernism were first shown in the major RSA exhibition in 1997, though they were presented as a young man’s experimentation with new forms before settling to his core subject: landscape. McPherson said he was “blown away” by the show, but felt something didn’t add up. “Here was a chap who could do anything, he had his whole life in front of him. I became increasingly dissatisfied with what was known - and not known - about him.”

It was the beginning of 17 years of detective work, trawling through archives, interviewing people who had known Gillies (who died in 1973), and looking at hundreds of paintings and drawings. His research reveals not only a completely fresh perspective on Gillies but surprising insights into the cultural politics of in post-war Scotland which led to his work being understood in a particular way.

William Gillies was born in Haddington in 1898, the second of three siblings. He showed an early talent for art and was encouraged by his maternal uncle, William Ryle Smith, an art teacher, who took him on painting trips. He went to Edinburgh College of Art in 1916, but was called up the following year, returning to in 1919 to complete his studies after fighting in the trenches.

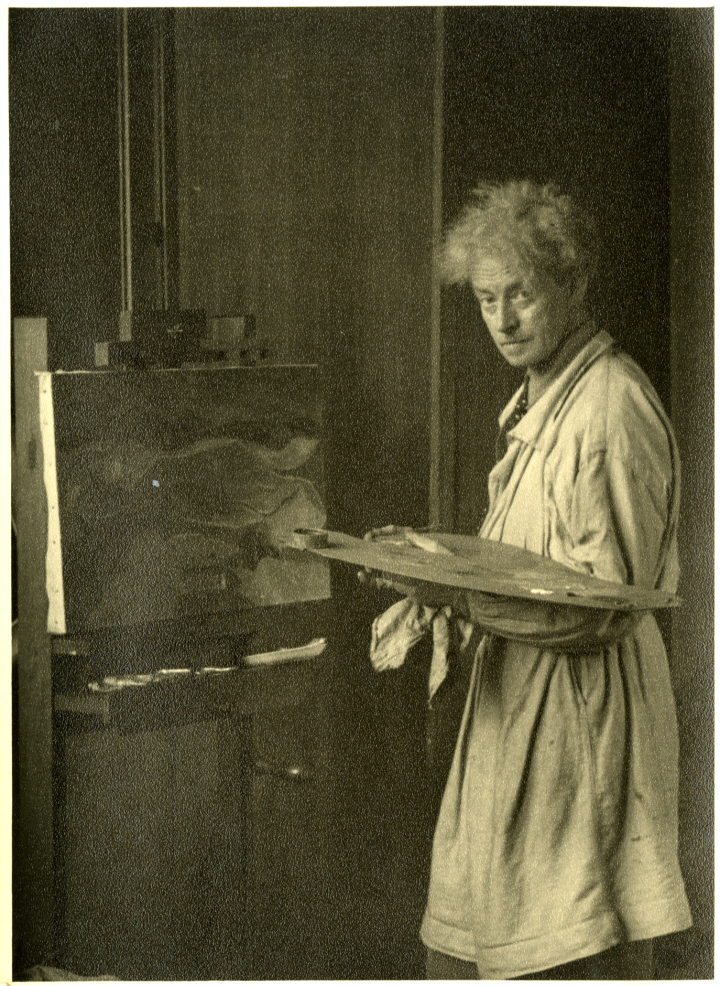

Paul Shillabeer, William Gillies at ECA, painting The Pentlands Mount Lothian

Paul Shillabeer, William Gillies at ECA, painting The Pentlands Mount Lothian

The (until now) definitive view of Gillies’ life, written by his colleague at ECA, Thomas Elder Dickson, and published in 1974, describes him as the product of an idyllic rural childhood who returned as a mature artist to the Scottish landscape and the quiet rural life. Subsequent books such as W Gordon Smith’s W G Gillies: A Very Still Life have reiterated this view.

However, as McPherson got a sense of Gillies the man, he felt that insufficient attention had been paid to his war experience. “He was not a countryman; he was an infantryman. His irony and wit, the dislike of hierarchy, the hands-on approach to life, the contempt for the top brass all fits so well with the attitudes of infantry privates in World War One.”

He believes that when Gillies travelled to Paris in 1923 to work in the studio of André Lhote, he was looking for a visual language to express the ideas he was grappling with, rejecting the Edwardian world view of his uncle in the light of his experiences in the trenches. “It was an absolute gift for him, because his whole world was in pieces. This is the nub of his modernism.”

Gillies would produce remarkable work over the next three decades: striking portraits, expressionist landscapes, experimental and semi-abstract still lifes, none of which have received the critical attention of his more conventional landscape work. Digging deep into the artist’s life, McPherson has revealed experiences which he believes underlie these works.

Gillies’ childhood, for example, was no rural idyll, but was lived in the shadow of a violent father. After what is believed to have been a minor stroke in 1905, John Gillies underwent a change, drinking too much and lashing out at his wife and children for the next 15 years. The family also laboured under the cloud of a hereditary thyroid disorder which would blight the health of both Gillies’ sisters, Janet (called Jenny) and Emma, and which he may have feared would affect him too.

McPherson was shocked when he discovered that Emma, who died aged 36 while a patient at the Royal Edinburgh Psychiatric Hospital, was misdiagnosed with “hysteria”: her death certificate revealed that she died of a thyroid illness. And further shocks were to come. On obtaining Emma’s medical records, he discovered a nine-page autobiography of the family written by Gillies for Emma’s doctors, revealing for the first time the impact of John Gillies’ violence. “I was so thrown by what I read I had to leave the library, my head was spinning. The account of the violence of Gillies’ father was truly shocking.”

As an artist, Gillies would use the language of modernism in the 1930s to explore these experiences in a series of portraits. In the remarkable ‘Interior’ (1937), in which he spliced time frames to depict himself, his mother and sister, he “used a whole series of modernist tropes to express so much about his life, his art, his predicament. It’s a painting that’s full of meaning, a sign that he absolutely got what modernism was about.” McPherson believes he was inspired by seeing the paintings of Edvard Munch, which were shown in Edinburgh in 1931 by the Society of Scottish Artists, realising that Munch “painted better for having engaged with the existential issues of his own life.”

.png) William Gillies, Interior (1938), oil on canvas, image courtesy of the Royal Scottish Academy and Bridgeman Images

William Gillies, Interior (1938), oil on canvas, image courtesy of the Royal Scottish Academy and Bridgeman Images

The engagement not only with the visual language but with the ideological basis of modernism marks him out as a true modernist. “It’s not just a young man’s experimentation. It’s modernism because there is something modernist to say. Modernism is a continuous, central and considered element in his work.

“There is nothing in British modernism to compare with his expressionist landscapes, and they look nothing like the Munch landscapes he knew at the time either. The expressionism is absolutely new. [Gillies is] an unrecognised part of the story of modernism in Britain. His art is rooted in the modernist critique of the tradition of academic painting in which he was raised, and it responds to the alienation and uncertainty of an age that has found the machine and was losing God.”

An extensive body of still lifes created between the 1930s and the 1950s explored themes of mortality and memorials; some paintings depict pots made by his sister Emma, who was a gifted ceramicist. “These paintings have been greatly underestimated. He is addressing how you find joy in a world where everything is terrible and dark. There’s a real journey from the very dark still lifes through to others where he is using black to push other colours forward, life enhanced by the darker side of life, not separate from it.” McPherson’s research reveals that, rather than seeking a return to the countryside in the 1930s, Gillies was enjoying bohemian Edinburgh. His purchase of the cottage in the Borders village of Temple in 1939, on the day war was declared, was more to do with finding a place of safety than embracing rural life. The family kept their Edinburgh home for another 10 years, hoping to move back.

The dominance of the narrative of Gillies the countryman is, McPherson says, “a puzzle that requires an explanation”. To do this, he had to plunge deep into the cultural politics of Scotland and London in the post-war years.

It was a contentious relationship in which London controlled the purse strings, and Scotland argued repeatedly for independent arts funding. A show of Scottish painting at the Royal Academy in 1939, organised by National Gallery of Scotland director, Stanley Cursiter, was poorly reviewed by London critics and led to Scottish art being considered inferior in the capital. Meanwhile, its defenders, who included Cursiter and Thomas Elder Dickson, tried to argue the case for a separate artistic tradition which deserved separate funding.

McPherson said: “In 1939, Elder Dickson was already making it his life’s work to right the wrong done by the 1939 pronouncements on Scottish art, to argue for artists who could only be produced in Scotland. Gillies fitted that argument better than anyone, and Elder Dickson manipulated his sources to suit his argument. It suited London too - if Gillies was a countryman, they could ignore him. No one challenged the truth of that basic assumption.”

Certainly not Gillies himself, who preferred to make no comment at all about his life, his art or his politics. It’s possible that the furious debate about cultural nationalism was a welcome smoke-screen for a man who valued his privacy. Whatever the reason, it has taken until 2024 for this prevailing view about his work to be questioned.

Even now, Gillies remains hard to pigeon-hole. He painted in a range of styles, some more experimental than others. He achieved significant recognition as a painter of landscapes, which remain popular today. McPherson calls him a “heroic sceptic”, sceptical of all big ideas, including modernism - “which is actually a very modern point of view.”

While this book and exhibition bring long overdue recognition for the multifaceted nature of his work, something of the man himself remains an enigma. Which is, perhaps, exactly as he would have wanted.

William Gillies: Modernism and Nation in British Art, by Andrew McPherson, is published by Edinburgh University Press.

The exhibition, William Gillies: Modernism and Nation, is at the John Gray Centre in Haddington until 26 April, and will tour to Rozelle House in Ayr, then around Scotland until December 2025, for dates see www.royalscottishacademy.org