Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

Victoria & Albert: Our Lives in Watercolour

By Carly Collier, 10.09.2021

Holding a pencil and with her sketchbook open on an easel behind her, Queen Victoria, accompanied by her two eldest children, turns away from the magnificent view of Loch Laggan framed by mountains that she was capturing in watercolours, to acknowledge a passing gillie. Sir Edwin Landseer’s arresting painting captures a fleeting moment during Victoria’s holiday in Scotland in the summer of 1847, when she was staying at Ardverikie House on the shores of the loch. An album in the Royal Collection contains ten studies by the queen made during her stay there when, unwittingly, she also made an artistic contribution to posterity, in copying murals that Landseer had painted in the house which were later destroyed by fire.

A few years later, Landseer’s work was reproduced commercially, and the print’s title, Her Majesty The Queen sketching at Loch Laggan, emphasised both Victoria’s appreciation of Scotland’s spectacular scenery and her love of painting from nature. Her views around Loch Laggan reflect her beginnings as a landscape watercolourist under the tuition of the Scottish artist William Leighton Leitch, which began in September 1846. Leitch’s tuition was comprehensive, covering the principles of composition, colouring, light and shade, and he set Victoria homework by means of painstakingly constructed demonstration sheets for her to study and copy. After a few short months, Victoria proudly wrote to her lady-in-waiting and fellow amateur artist Charlotte Canning, stating: ‘I have made great progress in my Drawing since I saw you’.

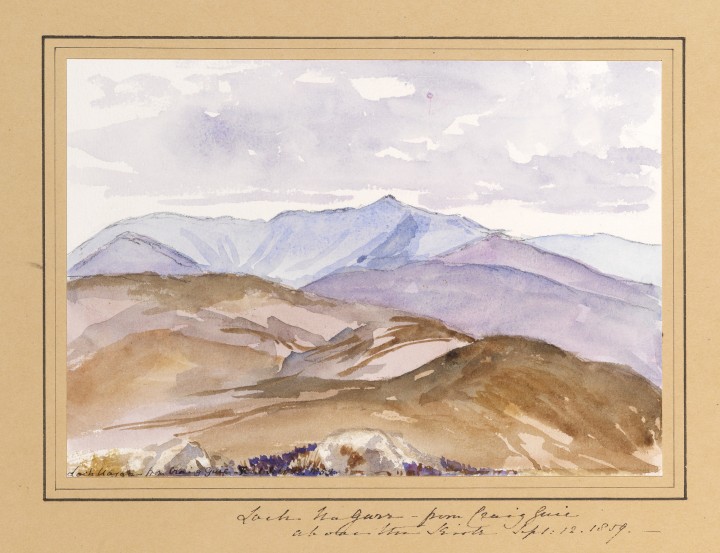

Queen Victoria, Loch Nagar - from Craig Guie above the Kirk, 1859

Queen Victoria, Loch Nagar - from Craig Guie above the Kirk, 1859

The improvement in the queen’s artistic skills from the late 1840s onwards coincided with Victoria and Albert’s discovery of the north-east of Scotland. In Deeside, they built a private residence, Balmoral Castle, which gave a welcome sense of freedom and privacy to enjoy family life. As she gained confidence as a watercolourist, Victoria’s bolder compositions and more painterly handling of colour were employed enthusiastically to record these new surroundings: ‘The Scenery all around is the finest almost I have seen anywhere. It is so wild & solitary, yet cheerful & beautifully wooded.’

The royal couple’s favourite local beauty spot was Lochnagar, the name of both a mountain and a loch on the Balmoral Estate – Albert thought Lochnagar ‘very like the Crater of Mount Vesuvius’, and Victoria described it as ‘one of the wildest, grandest things imaginable’. The queen painted the mountain and its surroundings over several decades from many viewpoints, paying close attention to different weather and light effects. Her watercolours are of a lyrical intensity that reflects her romantic, emotional attachment to the Scottish landscape; as she wrote to a relative in 1853, ‘I pine for my dear Highlands, which I get more attached to every year’. Victoria and Albert also commissioned several depictions of Lochnagar from professional artists, such as the view by the Aberdonian landscape painter James Giles, who was much patronised by the queen. The somewhat sparse and tonally muted treatment of the scene emphasises the landscape’s sublimity – a dramatic and romantic approach that would certainly have appealed to the queen and prince.

Queen Victoria, Mary Symons [and] Elizabeth Stewart, 1850

Queen Victoria, Mary Symons [and] Elizabeth Stewart, 1850

Carl Haag, Lizzie Stewart and Mary Symons, 1853

Carl Haag, Lizzie Stewart and Mary Symons, 1853

Though arguably her best work in watercolours stemmed from her careful observation of nature, Victoria’s keen interest in other people also spilled over into her artistic practice. She often drew those around her, including her own children and those of household servants. Here she depicts Mary Symons and Lizzie Stewart, whose fathers both worked on the Balmoral Estate. As is clear from her inscription, the queen drew the girls on separate occasions but grouped them together on this sheet. Again, a professional artist also painted the ‘dear little lassies’, as Victoria described them. In his large, fluidly painted watercolour, Carl Haag dramatically frames the girls against a rainy, rocky landscape.

Both Queen Victoria and Prince Albert wholeheartedly (and probably unwittingly) subscribed to an idealised view of Scotland and the Highlands. They considered its people to be untouched by modernity, and envied what they perceived to be a better, simpler way of life, close to nature. In this they were significantly influenced by the romantic portrayal of Scotland’s history and landscape presented in the poetry and novels of Sir Walter Scott. ‘Oh! Walter Scott is my beau ideal of a poet; I do so admire him in both Poetry and Prose!’, enthused the teenage Victoria in her diary. On an expedition to Loch Muick some years later, she recorded that ‘the beauty, poetry & wildness of the scene . . . quite put me in mind of Walter Scott’s lines in “The Lady of the Lake”.’ Scott’s works also provided picturesque subject matter for another of Victoria’s artistic endeavours which is perhaps lesser known. During her first pregnancy in 1840, the queen and her husband whiled away the time learning to make etchings. Over the next few years, the couple produced prints of a variety of subjects, often working collaboratively, as with the imaginative scene illustrating an episode from Scott’s novel Woodstock, which Albert designed and Victoria etched.

Queen Victoria, Scene from Scott's Woodstock, 1841

Queen Victoria, Scene from Scott's Woodstock, 1841

After Albert’s untimely death at the age of 42 in 1861, Balmoral became a sanctuary for the widowed queen. William Leighton Leitch wrote of his relief when, in 1863, Victoria resumed painting and drawing. She undoubtedly achieved a little solace through her sketchbook and colourbox, making views of the places she had first discovered with such joy in the company of her beloved husband.

Carly Collier is the curator of Victoria & Albert: Our Lives in Watercolour