Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

Uprooted Visions at Edinburgh Printmakers

By Greg Thomas, 18.05.2023

Studios of Sanctuary

Ethar Dira, Paria Goodarzi, and Antony Reznick have very different experiences of migration and conflict. But all were supported by In From The Margins, a residency scheme developed by Edinburgh Printmakers providing space and materials to artist-refugees. Greg Thomas spoke to the artists.

Led by Edinburgh Printmakers, In From The Margins offers month-long residencies to artists from refugee backgrounds. The participants, who have roots all around the world, travelled to studios in Cork, Amsterdam, Odense in Denmark, and Ljubljana in Slovenia as well as Edinburgh, but their work has been gathered together for the Printmakers show, Uprooted Visions,

I caught up with three of the artists to talk about their experiences. Ethar Dirar is a member of Arafa and the Dirars, an artists’ collective and family based in Hull. The Dirars are originally from West Sudan but were living in Libya – where Ethar was born – when the outbreak of war forced them to seek passage to the UK in 2015. Paria Goodarzi is an Iranian-born visual artist and community organiser based in Glasgow. Antony Reznik is from Kharkiv in Ukraine but fled the conflict in 2022 and currently lives in Berlin. The Dirars and Paria completed their residencies in Edinburgh, Antony in Cork.

GT: What were your experiences of being In from the Margins residents?

ED: Edinburgh Printmakers were really amazing at accommodating our needs. This was our first residency and we were new to printmaking, so the scheme allowed us to develop a lot of new skills.

PG: Also, there was a big network of artists from different places and that aspect of it really interested me. Plus, a lot of my work is participatory so this was a great opportunity to spend some time developing my own skills.

AR: At the time I applied for the residency I was in Lviv, a safe city in Ukraine, after escaping from my own city of Kharkiv....The residency gave me access to equipment and tools that I wouldn’t have had otherwise. My ideas are always in my mind but this was a chance to make them real.

GT: What kind of work did you make on the residency?

ED: Our piece is called Our Scar, and it reflects on the point when the bombing started in Libya, that one moment that changed our lives forever. Our work has always been about refugees and asylum seekers, seeking safety, but this is the first time we’ve explored our own experiences. It’s also the first piece which all five of us have contributed to, although we always work collaboratively. There is screen-printing, block-printing, and lino-cut in there.

Of course, the war in Libya was very traumatic. But the title suggests that maybe we’re lucky we have a scar instead of a wound. Lots of people are trapped, whether they’re in Sudan, Ukraine, or some other warzone. For them, war will never be a scar, it will always be a wound.

_screen printing and block printing on fabric.jpg) 'Our Scar (detail)', Arafa and The Dirars ,2022, Screen printing and block printing on fabric, image courtesy of the artist

'Our Scar (detail)', Arafa and The Dirars ,2022, Screen printing and block printing on fabric, image courtesy of the artist

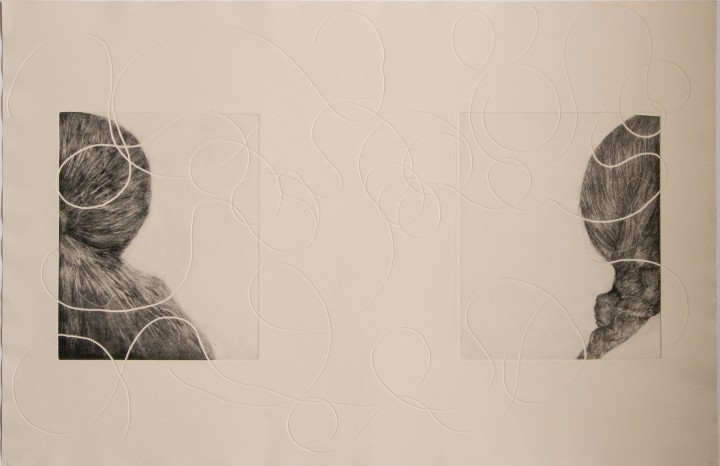

PG: My own practice has always focused on cultural and political identity, as well as displacement. I use a lot of interdisciplinary methods and there’s always a research basis. I carried all of that into the residency. The work developed around this idea of a connection between myself and my mum in Iran: between two people who are separated. This was at the time that the big feminist protests in Iran [the Mahsa Amini protests] were developing, so the piece was really well-timed, and the residency allowed me to bring these issues in Iran to greater awareness.

The work shows two female heads connected by threads, and it combines etching and screen- printing. The screen-print pattern comes from the details inside a British travel document, which I needed when I was applying for British citizenship. So it speaks to ideas of displacement and also the fact that, although I had this travel document, I couldn’t travel anywhere. I also incorporated my mum’s hair and my own hair onto the printing plate as a way of reflecting on that relationship.

AR: The pretexts for my work were Covid and my grandma. When I arrived in Cork I immediately got Covid and was locked in my room for a week. During that time I tried to call my grandma who lives in Donbas, which is occupied territory...She’s alright, but I couldn’t get a reply from her on WhatsApp that week, and that really worried me. Meanwhile, Covid made me feel very sick, like a bad acid trip [laughs]. I decided to combine these two feelings: a desperate wish to talk to my grandma and the Covid fever.

On WhatsApp screens there are lots of little pictures: of puppies, lips, and things like that. I decided to turn these into images of war. So, for example, I took this cute, stupid drawing of a puppy and changed it so it was carrying a human limb in its mouth, because my friend from Mariupol told me this story about a dog carrying a human leg along the street. So these very regular symbols of peaceful life, if you like, become pictures of hell, war, fear.

GT: How has your practice been shaped by experiences of conflict and migration?

AR: Well when I was a kid I always dreamed of visiting Ireland, and finally it’s happened [laughs]. And England too. It might seem like a joke but it’s not. In a strange way, the conflict has given me experiences I would never have had, although it is a tragedy.

ED: I would say that is very true. War and being a refugee has provided us with this situation where we feel we have something to express...In the refugee camp in Egypt, art was a way of surviving. It protected us from the terrible things happening around us, making art using the pens and paints that Red Cross would bring us.

PG: Another thing I would say is that if you’re coming from a different country, art allows you to communicate across language barriers by using a visual language that unites everyone. Art allows you to reflect on reality, on political situations, in ways you couldn’t otherwise.

Uprooted Visions, Antony Reznik, photo by Alan Dimmick, image courtesy of the artist

Uprooted Visions, Antony Reznik, photo by Alan Dimmick, image courtesy of the artist