Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

Trembling Together

By Greg Thomas, 24.01.2024

The Trembling Museum owes its title to a quote from the Martinique-born poet and philosopher Édouard Glissant (1928-2011):

“The earth is trembling. Systems of thought have been demolished, and there are no more straight paths. There are endless floods, eruptions, earthquakes, fires....Trembling thinking is the instinctual feeling that we must refuse all categories of fixed and imperial thought.”

Exhibition install photos by Fred Pederson

Exhibition install photos by Fred Pederson

The metaphor presumably held particular resonances for Glissant, whose home-nation was devastated by a volcanic eruption in 1902, the most deadly of the twentieth century. The evocative power of “trembling” appeals to the show’s curators, filmmaker Manthia Diawara and art historian Teri Geis, too. Indeed, one room is filled with artworks and geological specimens related to the Martinican eruption and volcanic happenings more generally, including some beautiful sketches by Ilana Halperin and trick video-footage recreating Mount Pelée’s convulsions, created by special-effects pioneer Georges Méliès (1861-1938).

Does Martinique’s volcanic past warrant the centrality of such themes to this exhibition (which features, for example, lava specimens punctuating the exhibits)? I’m not sure, but once this layer has been peeled back, we find an engaging selection of materials which invites us to think in new ways about how western and non-western (particularly West-African) cultures have informed each other over the course of modern history. Evidently, this has not always, or only, been through violent colonisation and extraction, but also through overlaid patterns of trade, migration, and mutual education.

Exhibition install photos by Fred Pederson

Exhibition install photos by Fred Pederson

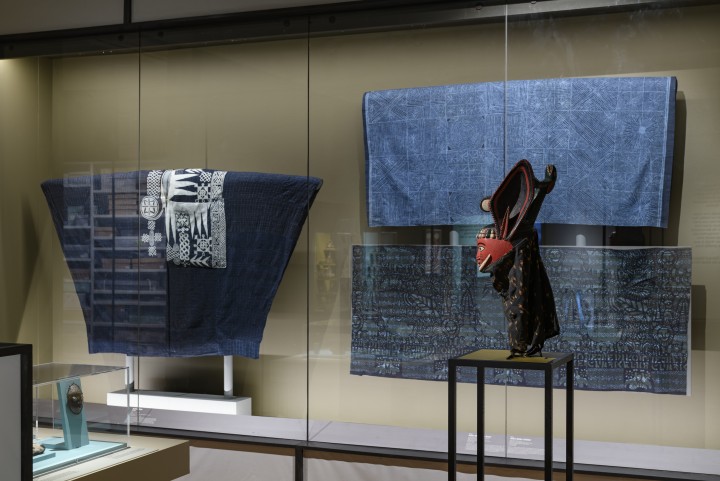

At the heart of the show is a selection of pieces previously held in the Hunterian’s “ethnography” store, raised here to their rightful place as artworks of profound invention, intensity, and verve. We find, for example, delightful Bamako ironwork from the 1970s recreating characters from Bambara (Malian) puppetry, an Ere Gelede Ogede or gorilla mask (1900-50) by a Yoruba artist used to venerate female ancestors, and a Qes Legesse painting of Saint George from the Ethiopian Orthodox tradition (1965-74).

Many of these works indicate a relationship of entanglement (or tremblement) bringing together African and European tropes and reference-points. Take the beautiful thornwood figures by Justus Akeredolu and Forge Craft Studios created for Nigeria’s tourist art-market during the 1950s-90s. Or the relief-engraved screen from Edo culture (1960-87) in which the traditional images of native rulers and enslaved people have been replaced by the British Governor and Royal West African Frontier Force (the identity of the enslaved remains the same).

Exhibition install photos by Fred Pederson

Exhibition install photos by Fred Pederson

These older works are married with contemporary pieces that propose, or emerge from, comparable processes of intercultural borrowing, collaging, splicing. In some cases the encoded narrative is a familiar one of resistance to enslavement and empire, as in Alberta Whittle’s ‘Power from Below: Decolonial Agents’ (2021), a sixteenth-century “colonial print” reproduced using woodblocks eaten by shipworms. In others, as in Leo Robinson’s abstract sculpture ‘Untitled (Oracle 1)’, European and African artistic tropes seem to influence each other in more lithe, esoteric ways.

Sometimes it’s hard to distinguish the posited aesthetic from a kind of bricolage-y postmodernism. But certainly, some of these contemporary works suggest a deepening and complication of contemporary artworld narratives around colonialism, and also propose the kind of “new sacred” that Glissant suggested might emerge from hybrid, postcolonial cultures. All in all, a complex, perhaps overcomplicated, but rewarding exhibition.

The Trembling Museum is exhibited at Hunterian Art Gallery until 24th May 2024. Read more here.