Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

Tracing Impressions

By Greg Thomas, 20.08.2021

In James McNeill Whistler’s The Black Hat (1900-02), Miss Rosalind Birnie Philip carries herself with something of the aloof grandeur of a Velasquez model, gazing with stern assurance through her layers of stiff, dark clothing. According to Glasgow University’s biographical note on Birnie Philip, this is about the closest Whistler ever came to a full profile of his wife’s youngest sibling, though a late lithograph takes in a similar proportion of her body. In general, these and other likenesses of Rosalind are seen to lack the warmth of Whistler’s paintings of his spouse Beatrice (or “Beatrix”), daughter of the sculptor John Birnie Philip. Nor do they possess the sultry, Berthe Morisot-esque elegance of Ethel Whibley, another sister, in works such as Mother of Pearl and Silver: The Andalusian (1888-1900).

‘Serious’ and ‘dutiful’ are amongst the words that hover around descriptions of Rosalind, much of our knowledge of whom comes from her letters to and from Whistler. Perhaps her correspondence with such a flamboyant and self-centred character simply squeezed out all traces of her personality. But in either case, it was Rosalind who cared for the artist and his mother on Beatrice’s death in 1896, and who, still in her twenties, was entrusted with the inheritance of Whistler’s estate when he followed in 1903.

James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Sketch for The Balcony, 1867-70. © The Hunterian, University of Glasgow.

James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Sketch for The Balcony, 1867-70. © The Hunterian, University of Glasgow.

By that time, the University of Glasgow had already established a relationship with the American-born aesthete and dandy. During the 1880s, a group of artists including Edward Walton, James Guthrie, Joseph Crawhall, and John Lavery, of varied British and Irish heritage but all resident in Glasgow, had taken Whistler’s expressive portraiture and fluid landscapes as a lodestar for their own experiments in Impressionist-inflected naturalism. At the start of 1891, Walton wrote to Whistler on behalf of the group – the so-called Glasgow Boys – to ask if his portrait of Thomas Carlyle, Arrangement in Grey and Black, No. 2 (1872-73), was still for sale, as they wished to raise a subscription to buy it for the city of Glasgow.

The bid was successful, and over the next few years, according to Ronald K. Anderson’s 1994 biography of Whistler, this group of artists several years his junior became his primary circle of friends. In 1897, when an article appeared in the Glasgow Evening News announcing the imminent formation of a new Art Society, taking as its members “secessionists from the Royal Society of British Artists,” it was the “amusingly impudent” Whistler who was named as prospective president. The new Society was partly established to boost the reputation in London of the Glasgow group, many of whom were now resident in the British capital but without a reputation there to match their continental acclaim.

For the vainglorious Whistler, the society’s creation was a chance to cock a snook at the RSBA, which had removed him as president in 1888 following various controversies mostly of his own making. But it also secured his emotional and artistic connection to the Glasgow Boys and to their home city. The mutual affection was confirmed through the awarding of an honorary Doctorate to the artist just before his death; in his delighted letter of acceptance, the ailing recipient drew attention to his Scottish ancestry through his mother’s family, the McNeills.

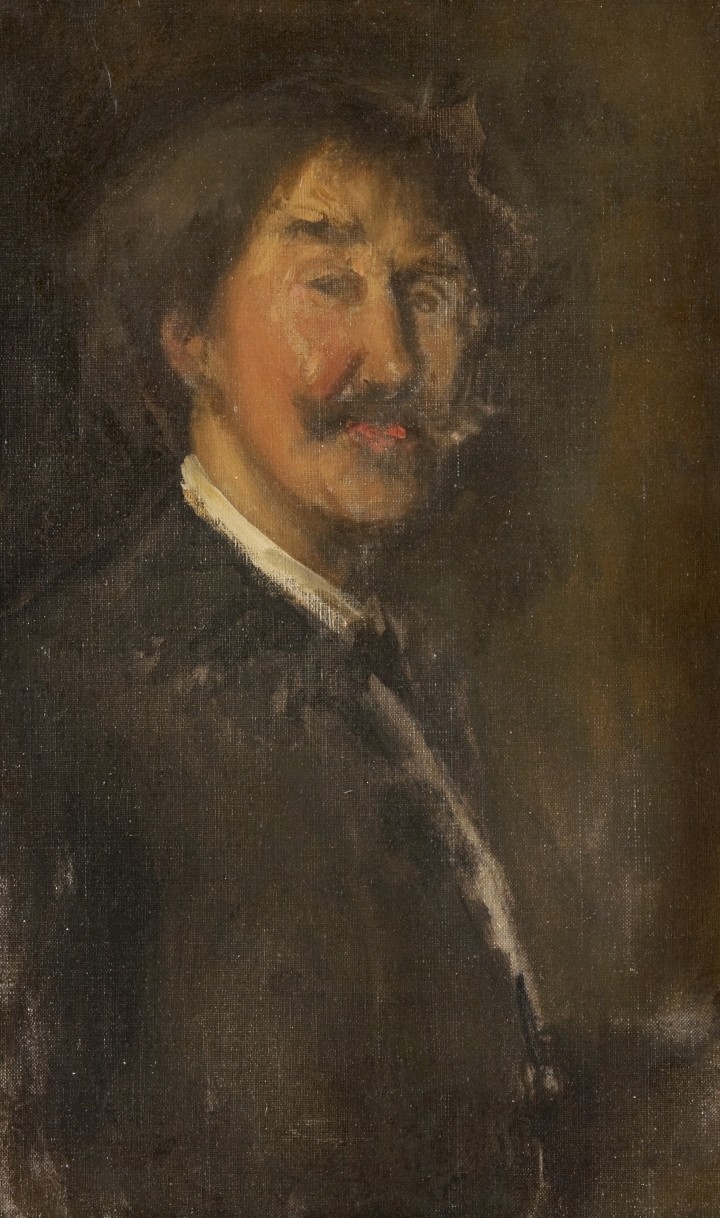

James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Self-Portrait, 1896-97. © The Hunterian, University of Glasgow.

James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Self-Portrait, 1896-97. © The Hunterian, University of Glasgow.

From 1903 onwards, it was down to siblings and offspring to firm up the bonds established over the previous decade. Edward Walton’s son John became Regius Professor of Botany at the University of Glasgow, but also served as an honorary curator of fine art. In this capacity, he helped the university to persuade Rosalind that it could provide a suitable home for her collection. She made her first major gift in 1938 – much of which can only be seen at the Hunterian – including paintings, prints, pastels and drawings. Six thousand letters, ledgers, books, catalogues, and press cuttings following in 1955. Finally, on Rosalind’s death three years later, the residue of Whistler’s studio was bequeathed to the university, including works on paper, manuscripts, books and prints, and large number of artworks by Beatrix, some of which appear in the current show alongside paintings by Walton and other acolytes.

The task of persuasion would, it seems, not necessarily have been straightforward. One posthumous incident that seems to shine a light on a quietly implacable personality concerns Birnie Philip’s refusal to authorise a 1908 biography of Whistler by Elizabeth and Joseph Pennell. Feeling that the authors had inflated a permission from its subject to print a catalogue of his work, Rosalind, according to the Pennells introduction to their book, “not only withheld such assistance as she might have given us, but put serious hindrances in our way.” One hindrance was, presumably, the lawsuit she brought against them in 1907, dutiful to Whistler’s legacy, and to his wishes that “no mendacious scamp” should peddle “foolish truths” about him. An “inordinately vain man,” Anderson notes, Whistler found “fiction...infinitely easier to cope with.”

'Whistler: Art and Legacy' offers an expansive chronological survey of a mercurial creative life, from intricate, gothic prints of the industrial Thames through to nocturnes, seascapes, and late Parisian and London city scenes. It is testament to the dutiful, serious work of the woman in the black hat.

Whistler: Art and Legacy is on at the Hunterian, Glasgow, until 31st October