Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

Time, Tides and Points of Departure

By Susan Mansfield, 24.06.2022

Will Maclean’s study is empty. Apart from a single stubborn painting he has been worrying at for a while, the work surfaces are bare, the tools neatly arranged. He is apologetic. It never looks like this. But that’s what happens when you have a major retrospective.

Will Maclean: Points of Departure is now underway now at Edinburgh’s City Art Centre (CAC). The retrospective, bringing together work spanning five decades, is the latest big survey show for a Scottish artist at the CAC, following Ian Hamilton Finlay and Victoria Crowe. Maclean, now 81, is a more-than-deserving subject.

We meet at his home in Tayport near Dundee where he and his wife of more than 50 years, artist Marian Leven, keep working studios on opposite sides of the house. He is gracious and unassuming, speaking quietly with just a hint of a Highland accent.

Maclean started out as a sailor. He grew up in Inverness where his father was harbourmaster, but really, he says, he lived in a “West Coast bubble”, escaping every school holiday to his mother’s folk on Skye, or his father’s at Coigach, Achiltibuie. All the men in the family were sailors or crofter-fishermen and the young Maclean wanted only to go to sea.

When less than perfect eyesight halted his Merchant Navy career after two years, he needed a fallback. “The only things I could remember being good at in school were art and gymnastics, so I applied for both and ended up in art school.” He chuckles softly. “Otherwise you would have been speaking to a retired gym teacher.”

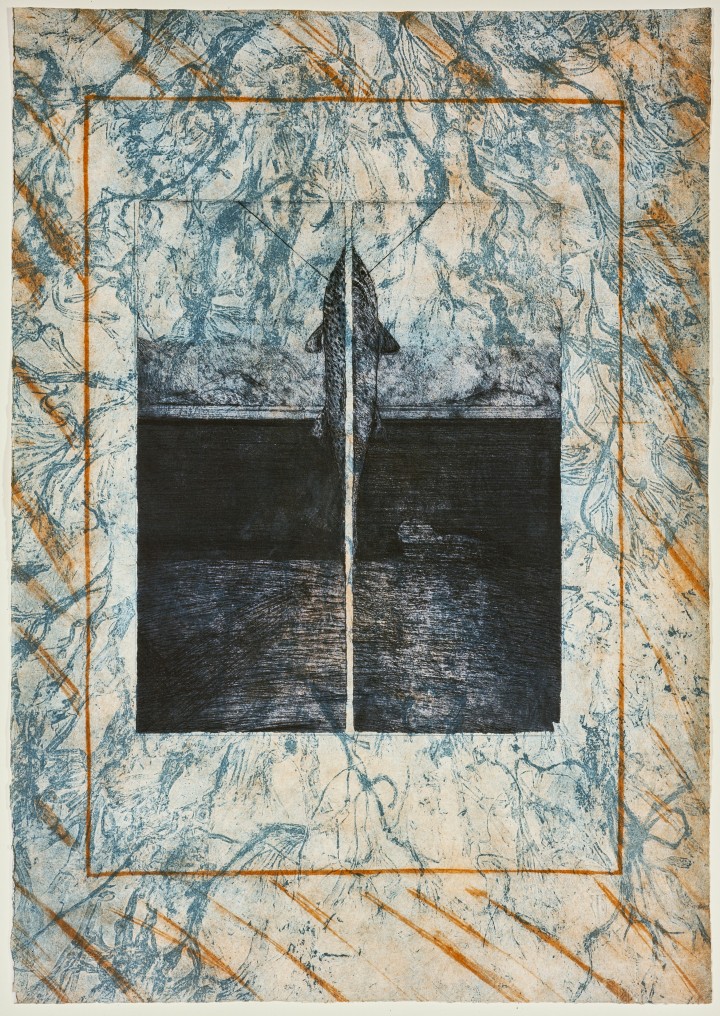

Will Maclean, The King’s Fish; 1991; coloured etching on paper, from A Night of Islands, suite of ten; 80 x 55cm; Royal Scottish Academy of Art and Architecture.

Will Maclean, The King’s Fish; 1991; coloured etching on paper, from A Night of Islands, suite of ten; 80 x 55cm; Royal Scottish Academy of Art and Architecture.

At Gray’s School of Art, Aberdeen, in the early 1960s, he specialised in painting. His diploma works were about the Highland Clearances. “The process of making art for me was always about something that was important to me emotionally, the history of the Highlands and the notion of the sea, that was at the centre of it. It was a process of finding a physical structure to fit that narrative.”

Painting never quite did that, he said, although he stuck with it for a decade and had solo exhibitions in 1968 and 1970, unusual for a recent graduate. In 1973, he took a sabbatical from work (he was teaching art at the high school in Cupar) to chronicle the dying traditions of ring-net herring fishermen on Skye. The drawings he made were swiftly bought by the National Galleries of Scotland.

However, when Jack Knox visited his studio in 1975 to select paintings for the opening of the new Fruitmarket Gallery, his attention was captured by a small box assemblage Maclean had been tinkering with. Inspired by the box constructions of Joseph Cornell, and drawing both on the surrealists and the scrimshaw of sailors, he was beginning to discover the language he would use for the rest of his career. Objects - sometimes found, sometimes hand-made, often painted - were being invested with meaning, memories, stories.

He was swimming against the tide. “At the time, the current thinking was that, as you progressed from art school, you progressed towards abstraction. It didn’t work for me, I needed a narrative. Cornell was a revelation because here was someone who was dealing with a narrative openly and transferring it into visual form.”

Another important inspiration was Gaelic poet Sorley MacLean. “I always wanted to make a visual contribution to Gaelic culture in the way that Sorley had made a poetic contribution. Sorley was a role model for me always because his poetry is so contemporary and so real and yet so intrinsically based in his own culture.”

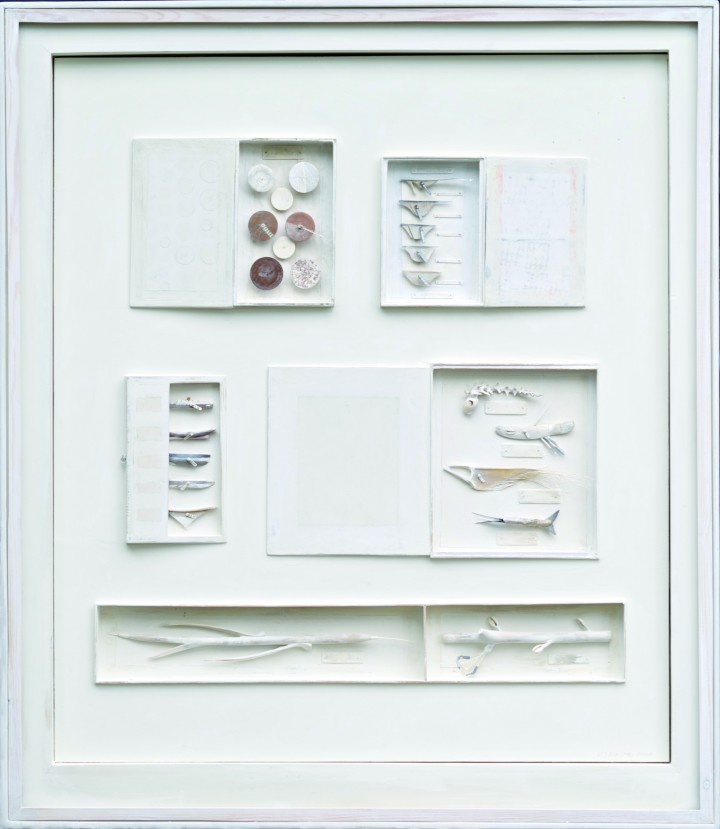

Will Maclean, Mariner’s MuseumTaxonomy of Tides; 2014; mixed media construction; 123 x 108 x 9.5cm; private collection.

Will Maclean, Mariner’s MuseumTaxonomy of Tides; 2014; mixed media construction; 123 x 108 x 9.5cm; private collection.

Having found his visual language, he enriched it by studying objects from Native American and Inuit cultures of the Western seaboard of North America. But looking to the past is only part of the story. Maclean was taking traditions, history, craft and symbol and fashioning them into new pieces through the lens of modernism. His works have such an ancient, totemic quality that one can forget how formally innovative they are.

Mysterious and redolent with meaning, his sculptures are often compared to poetry, and he has collaborated with poets from John Burnside to Kenneth White. To his delight, Sorley MacLean wrote the foreword to a monograph on his work published in 1992. Without much fuss or fanfare, he has produced consistently interesting work down the years, racked up an impressive catalogue of exhibitions, and has work in a long list of important collections. Through all this he continued to teach, joining the staff of Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design in 1981.

The 1990s brought an opportunity to adapt his work to a new scale, designing large sculptures for public contexts — cairns marking the key locations of the 19th-century land riots on the Isle of Lewis. Four sculptures, all very different, were built between 1994 and 2013, Maclean working with the communities to shape the designs.

“Like so many things in my life, it was something that happened, I didn’t go out to look for it. It’s not something I ever thought would happen, because by and large it’s a very solitary activity going to a studio and making art. I’m passionately interested in the subject, but it had to happen in consultation. If these things I designed were parachuted in as Arts Council sculptures, they wouldn’t have been received by the community in the same way.

“I was just part of a team and I fell into it happily. Looking back on it now, I think they are important because they refer to incidents which are an important part of history. If there is a monument, it is there for the next generation to say: ‘What are these things about? What’s the story here?’”

; 2013; photograph robin gillanders.jpg) Will Maclean, An Suileachan Memorial, Isle of Lewis (in collaboration with Marian Leven); 2013; photograph Robin Gillanders.

Will Maclean, An Suileachan Memorial, Isle of Lewis (in collaboration with Marian Leven); 2013; photograph Robin Gillanders.

An even greater challenge lay ahead. A new memorial was being commissioned to those lost in the Iolaire, the ship which sank at the entrance to Stornoway harbour on 1 January 1919, full of returning soldiers from the First World War. Unveiled on the centenary in the presence of the First Minister and the Prince of Wales, it was a long-awaited commemoration of an event so terrible it had been shrouded in silence for almost a century.

Maclean worked on it with sculptor Arthur Watson and Leven as project manager. “I think the three of us worked very well because Arthur had the specific things he wanted to do and I had mine, and Marian tied it all together. It was a great honour to be invited to do something that was so important to that community. Prince Charles made a heartfelt speech. It was a great celebration of a tragedy — if you can put those two words together.”

However, for any artist, the most exciting project is always the next one. More recently, he and Leven have been invited by the local heritage group to work on a public sculpture for Coigach, where resistance to the Clearances was particularly fierce and tenacious. Both the story and the location are close to his heart, and there are ideas on the drawing board. “We’ve got to try and balance. We don’t want it to be a memorial as such, or too specific, so there’s a lot of thinking going to have to go into it. That’s what’s exciting us now.”

Will Maclean’s retrospective Points of Departure is exhibited at the City Art Centre, until 2nd October, including one work on loan from the Fleming Collection. Time and Tides at The Fine Art Society is exhibited until 16th July.