Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

Things of the Flesh

By Greg Thomas, 19.01.2022

Flesh Arranges Itself Differently features artworks across a range of media, engaging with “the body” in the widest and most figuratively adventurous sense: from the body as locus of human sentience to the surgeon’s cadaver, the microbial and microscopic depths of the body’s interior, and the astral bodies of outer space and inner mind. In a sense, the show emerges as a set of responses to the anatomical body as elaborated in eighteenth-to-nineteenth-century European medical discourse: what curators Ned McConnell and Dominic Paterson call “the body…as an object of knowledge, as so many pieces, tissues and layers to delineate.”

An opening arrangement of watercolours by Robert Macaulay Stevenson, a student at Glasgow School of Art during the late 1800s (with a background, suitably enough, in engineering) sets the tone to be complicated later on. Exquisitely detailed, emotionally neutral studies of legs and feet, these works are subject to pre-emptive satire, as it were, by their placement next to a plate from William Hogath’s acerbic Analysis of Beauty (1753). Sequential sketches show the progression of the bodily ideal across times and cultures, throwing in bathetic references to ever-more baroque chair legs and outlandish wigs.

William Cowper, Écorché figures. University of Glasgow Library, Archives and Special Collections.

William Cowper, Écorché figures. University of Glasgow Library, Archives and Special Collections.

The colonial and misogynist substrata of Enlightenment science are engaged with more frontally by the contemporary work on display: notably in a series of sinister female nudes by Swiss painter Miriam Cahn, their pink nipples and genitalia almost unbearably vivid, as if exposed to a corrosive view. Elsewhere, Christine Borland’s claustrophobic film SimWoman (2010) shows the laboured mechanical breathing of a wax-coated model of the artist’s body. This was created after she learned that a company producing medical mannequins didn’t offer a female version—an encapsulation of medical enquiry’s ongoing gender gap. These works present the female body as an object that has been pored over and dissected by hostile forces. But a sinister energy pushes back: an unknowable, even monstrous quality.

Elsewhere in the show, Danh Vō’s doctored Andy Warhol print interrogates the statist and imperial dimensions of bodily discourse. A version of the pop artist’s electric-chair silkscreen is overlaid, in an elaborate gothic script, with the phrase “born out of a uterus I have nothing to do with.” In the face of Warhol’s slick cynicism regarding mechanised, state-sanctioned murder, the Vietnamese artist reinserts the human form into the image by visceral figurative association with birth. The gesture resonates with the artist’s wider engagement with Western military incursions into south-east Asia, including the violence done to colonised bodies. Pakistani artist Huma Bhaba’s What is Love (2013), a totemic figure carved from Styrofoam and cork, likewise seems to record the damage enacted on the human frame through colonial encounter, with its wretched features and expression.

In some respects, the humanist backdrop to enlightenment science was the victim of its own relentlessly inquisitive attention. After the Second World War in particular, when cybernetics and associated discourses began to quantify the possibility of intelligent life while placing human sentience on a spectrum with that of robots and animals, the body seemed a newly abject or alienated spectacle to many. This is reflected, though with the expected dash of technicolour panache, in a set of prints by Eduardo Paolozzi, exploring sci-fi graphics and robotics. Around the corner, Liliane Lijn’s light box Cosmic Flares III pulls focus to the intergalactic domains being probed during the same era, which made their own contribution to the reframing of the human body: the environments it could survive in and call home.

Huma Bhabha, What is Love, 2013. Courtesy the Roberts Institute of Art and the David and Indrė Roberts Collection. © Huma Bhabha.

Huma Bhabha, What is Love, 2013. Courtesy the Roberts Institute of Art and the David and Indrė Roberts Collection. © Huma Bhabha.

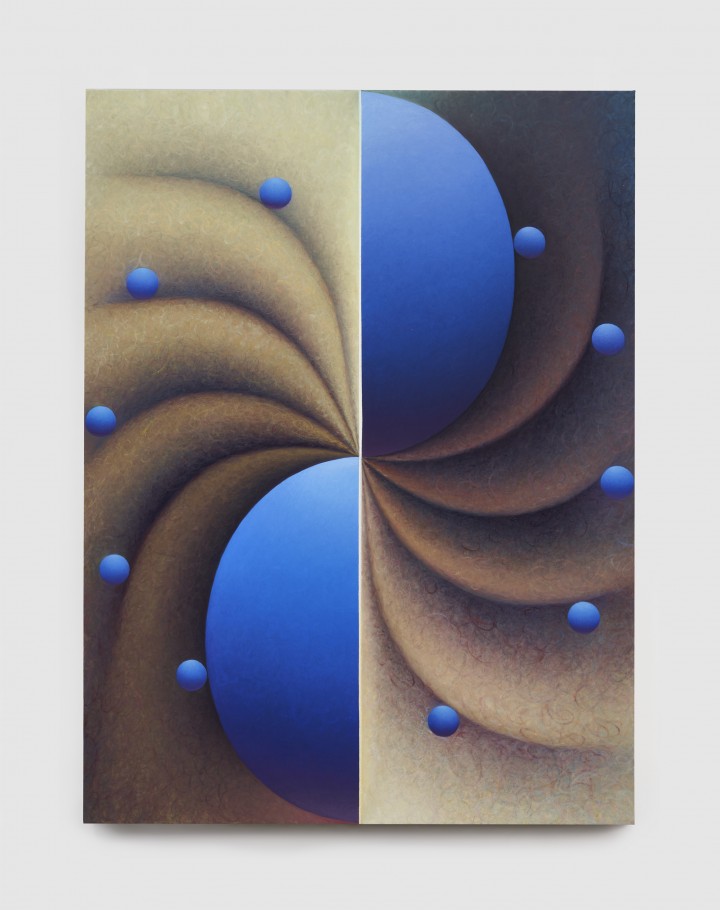

One of the curators’ most interesting contentions is that since the late twentieth century we have witnessed the emergence of “artworks that treat the artistic object itself as fractured, opened out, exposed to and imprinted by worldly or even otherworldly forces.” This engagement with inanimate materials and objects as worthy of attention comparable to human bodies – as animated by comparable forces of growth, articulation, and decay -- is borne out in interesting ways in the sun-bleached and dirt-coloured canvases of Somali-Swedish artist Ayan Farah. So too in Michael E. Smith’s Untitled (2015), an uncanny mixed-media work consisting, amongst other things, of a spine of tightly-wrapped rhododendron leaves set in urethane resin. Inert matter seems to be rendered sensate in some distressing way: twisted, pulled, even tortured.

Paterson and McConnell are clear in offering an open-ended rumination on the literal and figurative dimensions of their subject-matter, without neat enclosure. Indeed, beautiful works by Ilana Halperin, Tamara Henderson and others suggest different thematic routes across the show. A concise yet depth-filled spectacle, this exhibition invites each audience member to map their own path across the bodies of work on offer.

Flesh Arranges Itself Differently is exhibited at The Hunterian, co-curated with the Roberts Institute of Art, until the 3rd April 2022