Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

The Youngest and the Best

By Greg Thomas, 06.08.2021

, 2017, cast glass with metal oxide and soil, 85cm x 80cm x 35cm photo credit ewen weatherspoon.jpg)

Alexander Maclean, born in Polbain, Ross-Shire in 1860, apprenticed tailor in Ullapool, emigrated to North America in 1887. He lived and worked in Colorado and Nevada, earning a living with the skills he had learned back home before his wife died in a flash flood; some would use the phrase ‘mysterious circumstances’ to describe her demise. He vanished from the historical record for some years but later reappeared as an alderman in Reno, Nevada, where he died in 1925. This is not the plot of a revisionist western but a real-life, flesh-and-bones tale of expulsion, expansion, and resettlement. In the wake of the highland clearances and rural economic decline across the north of Scotland, MacLean was one of scores of men, women, and children who sought a new start overseas—or by heading south. “The youngest and the best,” a nineteenth-century Ullapool schoolmaster called these emigres.

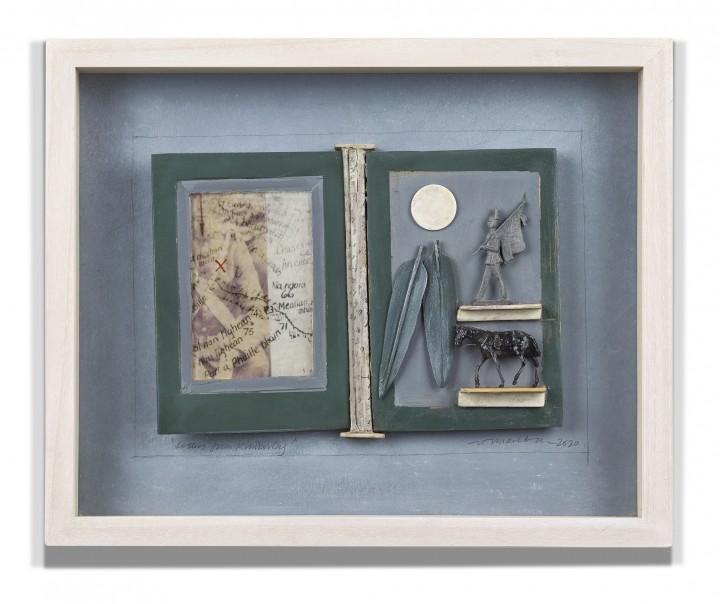

Alexander’s namesake Will MacLean takes as his theme those Scots who arrived in what would become known as Nova Scotia, lands from which the First Nations Mi’kmaq people were driven. Six residents of Polbain, all of them Gaelic speakers, are his subjects, each of their stories excavated in a triptych combining two framed, booklet-like constructions of resin-sealed collage, found objects, and whittled wooden talismans, bracketing a central pencil sketch: a palimpsestic and surreal landscape including elements of Celtic symbology.

Will Maclean, Letters from Kimberley. Courtesy the Artist and the Fine Art Society.

Will Maclean, Letters from Kimberley. Courtesy the Artist and the Fine Art Society.

The heritage of this work is perhaps partly in post-Cubist bricolage, but there is an attentiveness to the source of each symbol which cuts against any impression of random encounter or exuberantly repurposed forms. A layer of newspaper-print or period photograph forms the background to many of these little moulded constructions, from which snippets of information or visual data can be gleaned: “The Tailoring Firm of Gavin Baird is now open under the management of Alex MacLean,” reads one translucent scrap of Victorian advertisement, against a background of sepia farm buildings (in Canada or Ross-shire?). Across the spine – marked like a record-keeper’s booklet – we find a set of glass vials (tailor’s equipment?) labelled Ashes, Earth, Silver, and Water. Nothing is left to chance, but neither are the blank spaces filled for us. The mood of curiosity is what looking back into history ought to feel like: neither reverent nor judgemental, as literary critic Gerard Carruthers notes in an accompanying essay.

Shaun Fraser, Moine I, 2017. Courtesy the Artist and the Fine Art Society.

Shaun Fraser, Moine I, 2017. Courtesy the Artist and the Fine Art Society.

Interspersed with Maclean’s pieces are the earth and bitumen paintings of Shaun Fraser, an artist half a century Maclean’s junior, born and based in the Scottish Highlands. Whereas MacLean is an engineer of precisely imprecise forms, Fraser’s daubed canvases embody an earthier, more emotive energy. Action painting as memorial: liquid petroleum mingled with soil taken from locations significant to the artist flows freely across a set of deep, densely coloured frames, but with a tonal range to match Ad Reinhardt’s at this end of the colour spectrum. Fraser offers not only evocations of home but also of other people’s homes. A sequence of monoprints entitled Redrawn Terrain shows the outlines of sharecropper settlements built up by Scots immigrants by displacing First Nation residents. These pieces pose a question that hangs over the show as whole: were Scots settlers the victims or perpetrators of colonial violence? Narratives shift, the answers never sit still, truths are reconstituted. Suddenly it was always this way.

Owners of the Soul : Will Maclean and Shaun Fraser install. Courtesy the Fine Art Society.

Owners of the Soul : Will Maclean and Shaun Fraser install. Courtesy the Fine Art Society.

Fraser’s sculptures form a conceptual substratum to the exhibition in evoking a similar process of endless recreation, and are probably the most remarkable works on display. Casts were made of peat squares near the artist’s home, which, by a laborious process involving several stages of moulding and counter-moulding, were eventually rendered as glass sculptures, but with a sprinkle of the original turf added during the setting process. Like the opaque glass moose and deer antlers placed towards the front of the gallery, these objects are not what they represent, but they contain something of its essential character or composition.

Looking backwards to a national and transnational past, containing layered narratives of expansion, exploitation and resettlement, we never find what Carruthers calls “the real bad guys.” But through the murk hopefully some thread of meaning is carried through. An exhibition worth visiting.

Owners of the Soul : Will Maclean and Shaun Fraser is on at the Fine Art Society, Edinburgh, until 28th August, as part of the Edinburgh Art Festival 2021