Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

The Women that Shaped the Scottish Art Scene

By Susan Mansfield, 01.11.2015

In today's art world, questions about gender balance seem passé. Men and women have equal access to art education, and participate equally in professional practice. Describing a particular kind of art as 'male' or 'female' is not likely to win you friends.

For all that, two overlapping exhibitions in Scotland this autumn concentrate solely on art made by women. Together, they tell a story of women's art in Scotland over the last 130 years, reminding us that today's equality is a very recent thing, and that some unanswered questions on the subject may still remain.

'Modern Scottish Women', a survey show at the National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh, takes as its starting point the year 1885, when Fra Newbery (1855-1946) was appointed Director of Glasgow School of Art, opening up an era unprecedented opportunities for women artists, and ends in 1965, the year Anne Redpath died. 'Ripples on the Pond' at Glasgow's Gallery of Modern Art starts in the present day and works back 50 years through the Glasgow Museum's Collection (GMC), presenting works on paper, photography and film by contemporary women artists alongside those of Barbara Hepworth (1903-75), Joan Eardley (1921-63) and Bet Low (1924-2007).

Joan Eardley, Field of Barley by the Sea, Unknown, oil on board, Ⓒ Estate of Joan Eardley. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2019.

Joan Eardley, Field of Barley by the Sea, Unknown, oil on board, Ⓒ Estate of Joan Eardley. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2019.

The shows have very different purposes. 'Modern Scottish Women' concentrates on painting and sculpture - the art forms thought most traditionally masculine - aiming to reveal the women who worked on the cusp of modernism and who are often little known or exhibited today. 'Ripples on the pond' takes as a launch point a selection of prints from '21 Revolutions', the series commissioned to mark the 21st anniversary of Glasgow Women's library last year, and uses that as a ken through which to explore works on paper in the city's art collection.

'Modern Scottish Women' celebrates the achievements of women in painting and sculpture at a time when they were casting off the image of the lady watercolourist and training to become professional artists. 'There were very obvious inequalities: the number of female to male students, the number of female exhibitors to male at the RSA,' says curator Alice Strang. 'But, in general, I've tried to take a glass-half-full approach, celebrating the artists who did achieve, won prizes, had solo exhibitions.'

It was a time when women were fighting for access to life-drawing classes, long thought improper for ladies, but considered the linchpin of professional practice. Even in 1955, when Joan Eardley exhibited Sleeping Nude, a portrait of a male friend, visitors to the gallery were appalled by the idea of a male nude painted by a woman artist. But, at the same time, women were making their own strides forward in artistic innovation.

William McCance (1894-1970) and William Johnstone (1897-1981) are the two Scottish artists always described as the ones most engaged with developments in London between the wars. 'But what we've found out it is that McCance's wife, Agnew Miller parker (1895-1980), did the most extraordinary series of Vorticist-inspired paintings. By putting those on the walls, we're re-writing art history. Next time someone writes a textbook about Scottish art history and you have to include William Johnstone, William McCance and Agnew Miller Parker.' says Strang.

Many of these stories have not been told before, and were uncovered through historical detective work. Woman artists' careers are often differently structured: their work ebbs and flows to accommodate family responsibilities rather than accumulating steadily through a sequence of solo shows; names change with marriage; work passes to family members or is lost, Strang says: 'They don't have long careers in which to produce lots and lots of work. You have really talented artists like Mabel Pryde Nicholson (1872-1918), who died at the age of 47 - I think we know of 25 paintings that she made. They are not going to fill a gallery, so having a group exhibition allows us to show the work of lots of different artists together.'

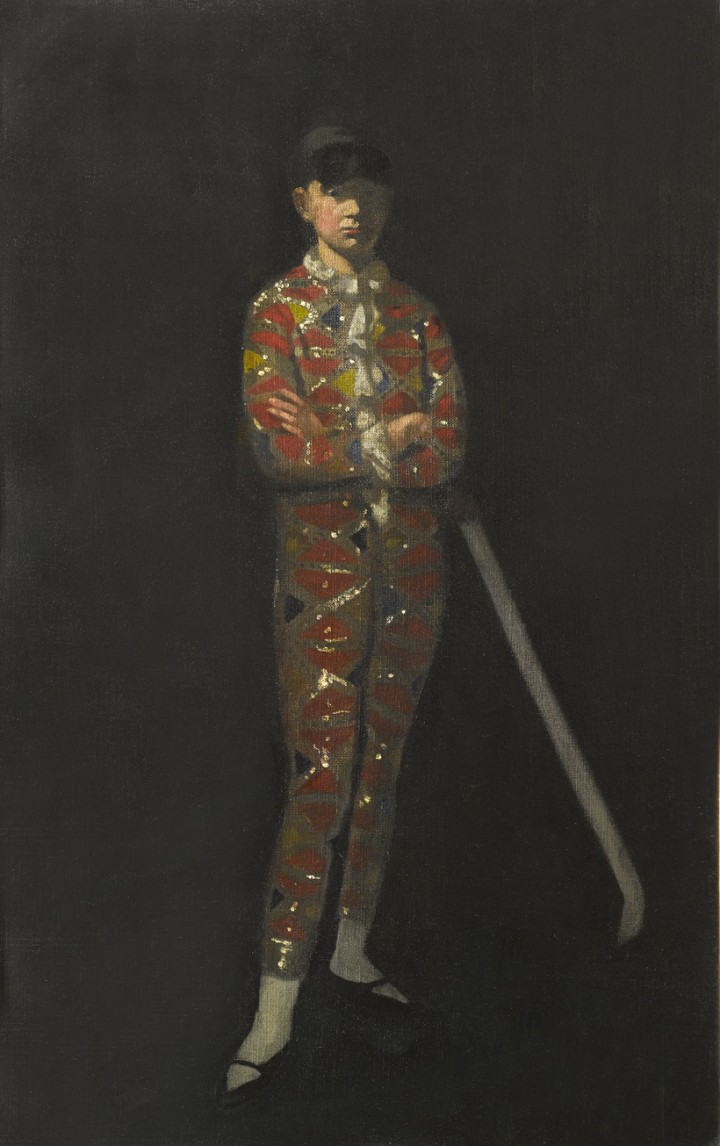

Mabel Pryde, The Artist's Daughter, Nancy, as Pierrot, Unknown, oil on canvas

Mabel Pryde, The Artist's Daughter, Nancy, as Pierrot, Unknown, oil on canvas

Katie Bruce, the curator of 'Ripples on the Pond', says that, although much has changed, domestic 'pressures' still interrupt women's careers: 'I think this is still an unspoken reason why women artists' careers ebb and flow more [than men's]. The personal is also often associated with women artists and their practice in a way that is never discussed about male artists, though it is slowly changing. I find it interesting that a lot of women work with the themes of time, disruption of time and the ephemeral in their work.'

Beginning with the prints from '21 Revolutions', including works by Ciara Phillips, Claire Barclay, Jacki Parry and Sam Ainsley, and with themes of play, landscape, portrait and the visibility of women's history and practice, Bruce began to look back through the Glasgow Museums' Collection. Remarkable works were discovered, including a rare print by Bloomsbury artist Vanessa Bell (1879-1961) and a watercolour by Bet Low, both of which are unlikely to have ever been shown before.

Bruce explains: 'For me, it was an exploration or a revealing of the work in the collection, and a repositioning of the work in the collection, and a repositioning of that work beside newer work, and starting a conversation around them. I'm interested in challenging the institutional exhibition as the voice of authority; for me, it's much more conventional, I want people to see connections. Works on paper are not necessarily seen as significant and I liked the idea of curating a large show of work on paper as a significant practice in its own right.'

Many of the women in 'Ripples in the Pond' are actively interrogating the question of what it means to make art as a woman. While she steers clear of defining 'women's practice' too closely, Bruce says: 'If I was passed about features or qualities particular to women's practice, I feel that there is often a personal element that deftly comments on or relates to the wider world. The body, for example, or personal history is used to make work that relates to global issues or makes us think about our place in history or time.'

Of the modern Scottish women Strang sought out, some depicted subject matter one might consider typically 'female' - domestic interiors and portraits of their children - while others ranged much more widely - Eardley painted the sea at Catterline in the teeth of a storm and Mary Cameron (1865-1921, known as 'Bloody Mary') painted bullfights in Spain at the beginning of the 20th century. Strang elaborated: '[Cameron's] work is astonishing, technically brilliant, compositionally ambitious and very graphic. When she was interviewed for magazines, they'd make a big deal of the fact that she's pretty, but she's having none of it; she shows them her muscular, sun-tanned hands from working outdoors.'

Both curators agree that there continues to be value in exploring women's work in isolation. The making of both exhibitions has raised questions about the visibility of women artists in public collections. Bruce says: 'There are still questions to be asked about institutions and women artists, what we show and what we acquire. There is still a sense that, although there are women on the Turner Prize shortlist, there are a lot of women artists and curators, tutors and gallery directors, but a lot f the key positions at a national level are held by men and the big retrospectives are still of male artists. there are still conversations what are not finished.'