Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

Tangled Intensities

By Greg Thomas, 24.11.2020

Lily Briscoe is in my mind as I explore Sara Barker’s 18 new works at Cample Line, showing until the end of January. Briscoe, the protagonist of Virginia Woolf’s To The Lighthouse, spends the majority of the novel toiling over a painting in the garden of her adopted family’s holiday home; its summary stroke, enacted in the final paragraph, serves both to unite the composition and render it a motif for the structure of the narrative: two halves connected by a line. It is not just a victory for Lily but Woolf’s final word, nudging us ironically towards a wordless summation of the relationships, moods, and ideas she has spent 250 pages broaching through language.

Sara Barker is, as some reviewers have noted, an avid reader. It’s perhaps no surprise, then, that these works convey the same sense of an attempt to visually manifest ideas formed in language—or through encounter with language. It might be the orthographic hints of the tangled steel wire jutting out from the metal or plywood backdrops, or the sense of rising and receding images – like shapes that form in the mind when reading – generated by the loose figuration of the painting. Barker often uses the phrase “the edit” to describe the realisation of her work; it’s a process clearly haunted by language. Each piece here has a subtitle which is also a kind of collage poem: “tranquiliser/ river runs/ drift/ pick/ flake/ scatter”. Some works also incorporate letters and phrases. Dart, to whom the above accompaniment belongs, is named after an Alice Oswald poem, the title-word picked out in bent brass rod on a small plywood ledge.

Sara Barker, Dart, 2020. Courtesy the artist and Cample Line. Photography by Mike Bolam.

Sara Barker, Dart, 2020. Courtesy the artist and Cample Line. Photography by Mike Bolam.

That’s not to say that there aren’t ample analogies to art history here as well. Barker’s most ambitious works up to this point have often been realised on a larger scale, from those included in her 2016 show at Edinburgh’s Fruitmarket Gallery to The subtle knife, a 2013 installation for Newcastle’s BALTIC Centre, created in collaboration with Ryder Architecture. Sculptures formed from painted metal frameworks, some incorporating panels of glass, they have something of the scale and artful, half-formed quality of 1950s British abstraction: Anthony Caro, perhaps, but without the slick monochrome finish and more spindly, gestural, and human-made in quality. Here the scale is reduced, reflecting the practical circumstances of the show’s creation, during COVID-19 lockdown, when Barker’s house became her studio. There are echoes of Constructivist or Cubist relief work – Tatlin, Picasso – while organic and decorative details in works such as wait and mouth suggest Matisse’s jazzy cut-outs. Bristles of jutting wire in Hairs bring to mind the uncanny corporeality of Eva Hesse’s studio pieces; a row of thin silhouettes in End recreates in two dimensions Giacometti’s emaciated forms.

Sara Barker, Installation shots of 'undo the knot' at Cample Line, 2020. Courtesy the artist and Cample Line. Photography by Mike Bolam.

Sara Barker, Installation shots of 'undo the knot' at Cample Line, 2020. Courtesy the artist and Cample Line. Photography by Mike Bolam.

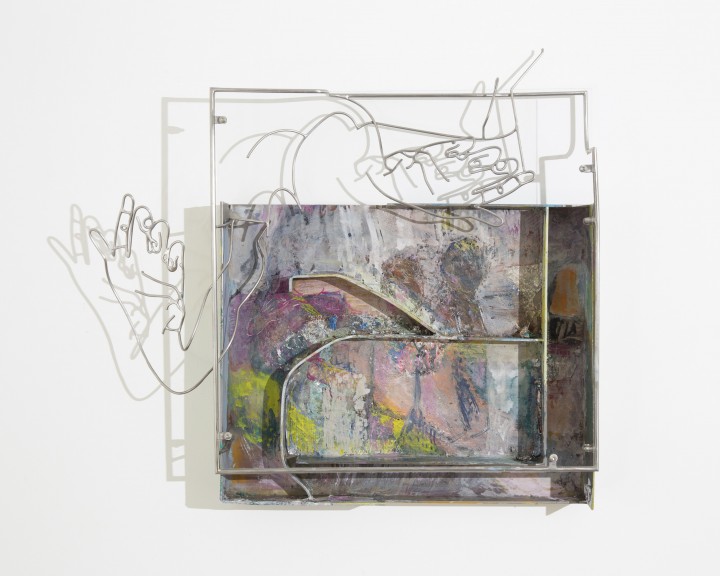

As a painter, Barker masters the space between figuration and abstraction. Indeed, the fact that she first trained as an artist on canvas makes more sense the more you intuit the common format of the pieces: an outward-facing, shallow steel tray, wall-mounted, painted or pastelled to create a gritty background frieze or landscape, a top layer of metalwork jutting outwards as if half-animated forms were exiting the frame. It seems like an intuitive formal extension of painting rather than a sculptural process incorporating brushwork. And much of the emotional and cognitive sense is carried by the background scene. We can almost see shallow hillsides, dry-stone walls, beaches (unable to visit the gallery in the early stages of preparation for the show, Barker searched online for images of the nearby landscape). Bodies, anonymous but familiar-seeming, rise up from scratchy patches of colour in toy and BUNKER—Barker’s obvious skill as a figurative painter is vital in ensuring that these hints stick in the mind.

Sara Barker, mouth, 2020. Courtesy the artist and Cample Line. Photography by Mike Bolam.

Sara Barker, mouth, 2020. Courtesy the artist and Cample Line. Photography by Mike Bolam.

Whether the frame of reference is writing, sculpture, or painting, it’s perhaps the homely scale and domestic connotations of the work that ultimately tie this sequence together. Barker has noted that the pieces often recreate the size of a book cradled in the arms, or of a laptop screen. When we start to think about the works as taking form in a mind looking at a screen or page, sat at a table looking out of a window, ambiguity starts to resolve itself. Rows of soft-edged rectangles in GAP become a sprawling bookshelf; stepped ziggurat patterns in outline become an interior staircase; hanging appendages in mouth become earrings or mantel-top trinkets; the piece’s playful bird-like shape is a cheese plant or kettle. We also get a sense of “the edit” in process from some works in the show. Maquette or model-type pieces such as hold and Split might not, Barker notes, have found their way into an exhibition conceived in the more formal space of the studio.

Joint, the first work in the sequence, serves as something of a statement of intent, then, a pair of steel hands and arms extending outwards from its frame as if preparing to mould cognitive space into physical form. The pleasure of these works lies in inferring that sense of fogged thought given substance and clarity, a knot untangled. At the risk of reducing them to documents of a very specific cultural moment, they perhaps express the freshness of perception that we are all seeking in our little domestic bubbles.

Sara Barker, Installation shots of 'undo the knot' at Cample Line, 2020. Courtesy the artist and Cample Line. Photography by Mike Bolam.

Sara Barker, Installation shots of 'undo the knot' at Cample Line, 2020. Courtesy the artist and Cample Line. Photography by Mike Bolam.

Sara Barker, Undo the Knot, Cample Line, 31 October – 31 January. For more info and booking details visit Cample Line's website.