Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

Stormy Waters

By Greg Thomas, 16.02.2021

“Fishing has always been part of my existence,” Joanne Coates notes in her back-cover blurb for North Sea Swells, a recent instalment in Another Place Press’s 'Field Notes' series. “Trips to the shore every weekend with my Nanna and Grandad. Obsessing over tales told from family maritime connection. [But] my links with the fishing industry were limited to the Yorkshire coast.”

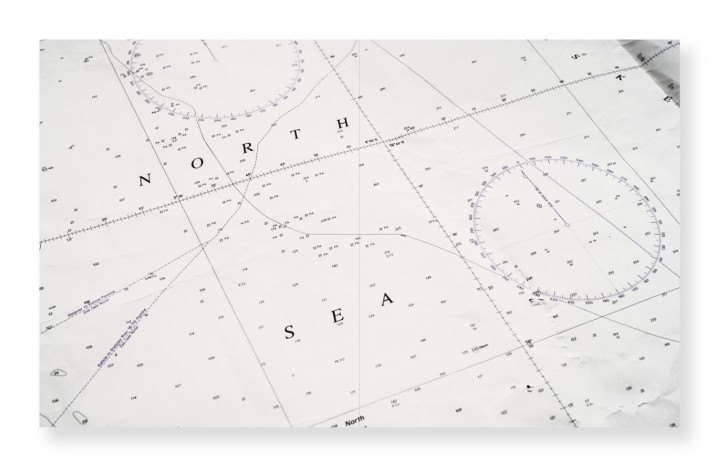

The project documented in this slim photo-book began in 2012, taking Coates the rest of the way up Britain’s north-east coast and off across the Pentland Firth to the Orkneys. “I was a working-class lass studying in London, this wasn’t going to be easy. The journeys were long, and mainly by bus and freight ferry. Nervous about being an outsider, wanting to connect, and to learn, not to take and to leave.”

Joanne Coates, North Sea Swells, Field Notes 021, 2020. Courtesy Another Place Press.

Joanne Coates, North Sea Swells, Field Notes 021, 2020. Courtesy Another Place Press.

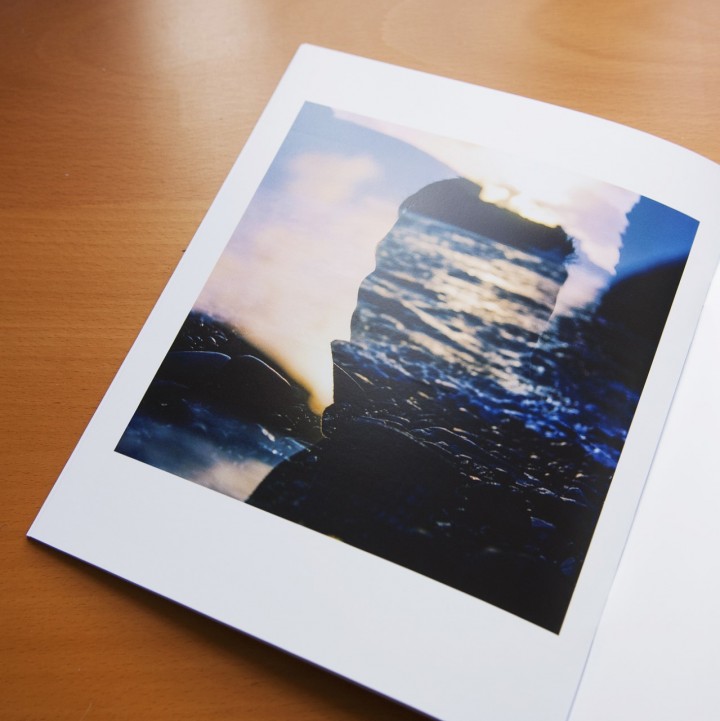

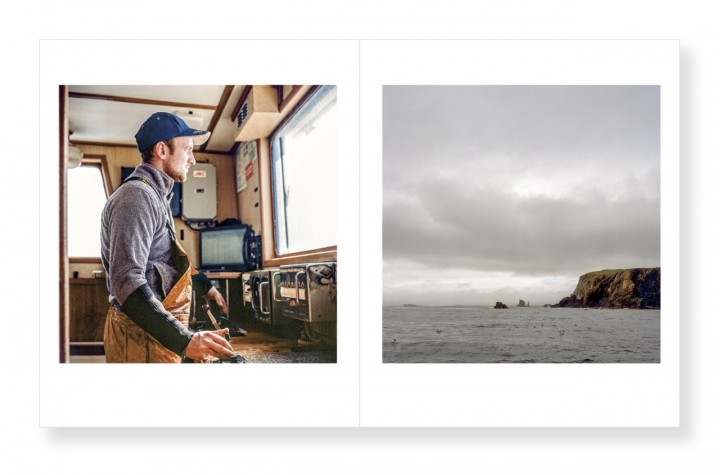

Aesthetically the images in this booklet are a delight: rich blues, greens, and ochres, luminous oranges and yellows, seem to give every surface the hue of brightly rusted steel or dazzling marine paint. There are snippets of theatrical detail: a fuel counter sits atop a locked cabinet; a clenched forearm reveals a Casio watch and a watery tattoo of a clipper ship; half a bottle of rust-coloured Irn Bru stands discarded next to a craft knife. Boats in dry-dock or warehouses offer the faintest hint of ocean-liner-aesthetic modernist glamour, offset by the grey concrete environs. But it’s the social backdrop to the photographs that really secures their potency.

A February 2016 article in Fishing News described the Orkney fishing industry as dependent on “a combination of shellfish and whitefish, landed by a mixed fleet of some 60 locally-owned +9m creel boats, scallopers and trawlers,...of vital socio-economic importance to local communities.”[1] The “twin-pronged” threat to the sector at that time came from the encroachment of Marine Protection Areas and “renewable energy interests” (the kind of concerns that might tempt a distant spectator to write off the Orcadian fishing industry as necessary collateral in the fight against environmental damage.) Then Brexit unfolded in excruciating slow motion, with the end result of a fishing deal described as “betrayal” by industry representatives. Amongst other things, Scottish vessels face the prospect of increased bureaucratic barriers to trade with Europe and the possibility of bans from mainland waters, alongside hiked export taxes.

Joanne Coates, North Sea Swells, Field Notes 021, 2020. Courtesy Another Place Press.

Joanne Coates, North Sea Swells, Field Notes 021, 2020. Courtesy Another Place Press.

Against this fraught background, Coates offers us images of working men – exclusively men – undertaking hard physical work with a sense of unselfconscious engrossment. They do not seem ostentatiously noble or joyful so much as entwined or immersed in their environment (the final, double-exposure image counterposes a silhouetted head against evening waves). Indeed, it’s the expressions and body language that Coates has been able to capture that both consolidates the artistic qualities of her work and pushes it beyond aestheticisation into the realms of intimate social documentary. There’s something particularly refreshing and tender about Coates’s treatment of (one version of) working-class masculinity, subject to so much classist disdain in the post-Brexit landscape.

North Sea Swells made me think about Mark Jenkin’s 2019 film Bait, a portrait of a local fishing industry in demise at the opposite corner of the British Isles, executed with a combination of aesthetic skill and ethical investment. Though on a smaller scale, Coates has produced a similarly nuanced work here, offering us pleasure in colour, light, texture, and minimalist narrative, while navigating a stormy social issue with subtlety and clarity of purpose.

Purchase the photobook from Another Place Press.

[1] David Linkie, “Fishing in Orkney: Part 1.” Fishing News, 3 February 2016.