Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

Spite Your Face

By Neil Cooper, 01.05.2017

The result of this for Maclean, following a ten-day script-writing session in Venice last December, is Spite Your Face. This new 30-minute film was commissioned and curated by the Scottish Borders-based Alchemy Film and Arts in partnership with Talbot Rice Gallery and the University of Edinburgh.

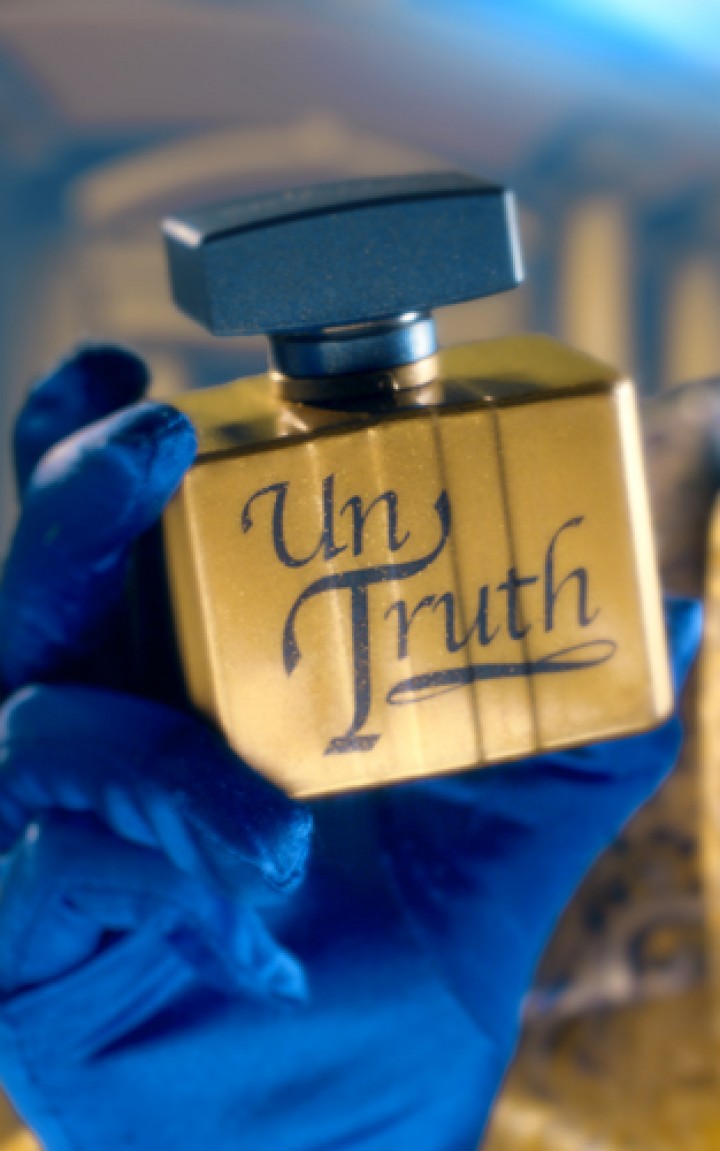

Maclean’s recognisable tropes, drawn from the pop cultural ephemera of girls magazines, MTV videos by the likes of Lady Gaga and Katy Perry, Disney films and computer games, here looks to Pinocchio. The puppet boy whose nose grows every time he tells a lie was originally brought to life in a novel for children by Italian writer Carlo Collodi in 1883. Despite numerous adaptations, the story probably remains best known from Walt Disney’s 1940 cartoon film.

‘It was shortly after Brexit, and Donald Trump had been elected,’ says Maclean, ‘and the Italian election was happening as well, so it was a very scary moment politically, but it was also exciting to be there. I hadn’t been in Venice at that time of year before. It’s quieter and spookier. Quite a lot of the script came directly out of that post-Brexit climate, about truth, lies, post-truth, and how lies had been used in the Brexit campaign.’

Rachel Maclean, Spite Your Face, 2017. Digital video. Courtesy of the artist.

Rachel Maclean, Spite Your Face, 2017. Digital video. Courtesy of the artist.

Since studying painting and drawing at Edinburgh College of Art, Maclean’s films have grown to become a body of what look increasingly like a series of skewed state-of-the-nation commentaries. While the early confections of Lolcats (2012) looked like a candy-coloured dreamscape culled from the unintentionally trippier end of children’s TV, Feed Me (2016), which was featured in British Art Show 8, looked at the infantilisation of adulthood in a way that mashed-up Barbie, Disney princesses and Britney Spears.

Please Sir (2014) similarly dissected class division and austerity culture through cutting up The Prince and the Pauper and Oliver Twist with Britain’s Got Talent and Jeremy Kyle. In a dizzying feat of cosplay-inspired shapeshifting, Maclean generally plays every role in all of her films. Spite Your Face sees Maclean expand her canvas even more.

‘Like a lot of my work, it uses these displaced fairytales,’ she says, ‘and because I was in Venice, I looked at Pinocchio, which is a story that’s very close to Italy, and I wanted to look at that through the lens of everything else that was going on. Fairytales help substantiate people’s ideologies, and if you look at how lies were used in the Brexit campaign, the narratives the politicians used over-simplified things, but they still related to people. Facts can be thrown at them to disprove them, but they do nothing to change people’s worlds.

‘This time, I’ve not looked at political speeches literally, and there are musical theatre elements in there that relate to Pinocchio, so there’s something of the language of fairytales in there, but, like my other work, the characters and the narrative are unstable.’

Maclean’s sensory palette is broader here too. ‘Spite Your Face has got quite a different colour scheme to my other work,’ she says, ‘which I think came out of being in Venice. It’s still bright and pretty gaudy, and it still references pop cartoons and children’s TV, but it’s also really very baroque, in the real, literal sense of the word.’

Spite Your Face is housed in Chiesa di Santa Caterina, Cannaregio, a deconsecrated church originally built as a base to uphold moral authority and reaffirm a political-religious power-base. For Maclean, the connections are perfect.

‘The work is lent an aura of the church just by being in one,’ she says. ‘I’ve always been interested in renaissance painting and Italian painting, both of which look quite a lot at truth, so there’s a similar sense of perspective.’

While it may not be explicit in her work, Maclean has spoken previously of how it is driven in part by anger. Issues of class, gender, nationhood and power have all been explored by her practice. Given everything that has happened over the last few months, Maclean’s anger might be more obvious than in previous work.

‘I think, like a lot of people, that the resurgence of white male privilege and its complete lack of substance is really worrying,’ says Maclean. ‘Before, those attitudes were dormant, but to see it rear its ugly head again now in a way that normalises that sort of behaviour, it makes me angry that those behind it will try to manipulate people who had a real reason to be angry.’

As with her other films, Spite Your Face was filmed using green screen, with Maclean colouring in each fantastical backdrop with computer-generated graphics. Where many of her films have utilised cut-ups of TV and film to provide the dialogue, here Maclean’s own script is voiced by actors. She has used other voices in this way previously, even going so far as to have actors appear physically in her gothic-inspired film for the Mull-based Comar organisation, The Weepers (2014). Both suggest a growing confidence is blooming behind her multitude of masks.

Rachel Maclean, Spite Your Face, 2017. Digital video. Courtesy of the artist.

Rachel Maclean, Spite Your Face, 2017. Digital video. Courtesy of the artist.

‘I think Spite Your Face feels the most narrative-based of my films,’ says Maclean. ‘I’m filming the narrative in a more formal way, so it’s not as fragmented. I’m really interested in running with something that’s more linear.’

Despite such streamlining, Maclean remains conscious of the context in which Spite Your Face will be seen.

‘Showing the film in a gallery is different from it being seen in a cinema,’ she says, ‘because people are coming in at different times, so I’ve tried to make it so there’s no beginning and no end, and it just goes round and round.’

As her work has grown more ambitious, Maclean’s increasingly formal tone, that goes beyond the subverted trappings of pop video bubblegum, could potentially develop into something that would sit in both art-house and multiplex cinemas.

‘I keep developing larger ideas,’ she says, ‘and I get quite excited about how you can develop characters over a longer period. Working with Alchemy already feels somewhere between the art world and cinema. One ambition of mine is to write a treatment for something much bigger. There are so many different ways of looking at how I might do that, but I really like the idea that work can relate to people outwith the art world. Even using Pinocchio and stories that people know, but done with layers of complexity beyond that, really appeals. Working in cinema really appeals in that way, but I don’t see me moving out of the art world either.’

Given the wild theatricality of her films and a clear love of rummaging through the dressing-up box to become a multitude of characters, Maclean is having tentative thoughts about bringing her work into the live arena.

‘I have this idea of developing work into some kind of live performance,’ she says. ‘I’m not sure how I’d do that yet, but it’s another way of expanding things. I’d probably work with actors rather than be in it myself. It’s a big leap to do that, but I like theatre that uses video within it, so maybe it could move between video and live performance, but I don’t know yet.’

Whether she ends up as director, performer or designer, Maclean is already an auteur whose creations could easily burst through the screen to become extravagantly realised Busby Berkeley-style epics. In the meantime, Spite Your Face will receive its UK premiere at Talbot Rice in 2018. By then, the world may have changed again, but chances are Maclean’s film will still chime with the times in the most audacious and playful of ways.

‘I hope Spite Your Face reflects something of what’s happening in the world just now,’ she says, ‘and that politics is seen through a different lens and a different language than it being discussed purely through journalistic means. By interrogating ideas about truth and lies, and illuminating that through fairytales, hopefully people who see the film will be able to get something about what’s going on in the world in a different way.’