Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

Sam Ainsley

By Rachael Cloughton, 01.09.2017

Sam Ainsley is officially an Outstanding Woman. Earlier this year, the Saltire Society awarded her the title, which is shared by a small group of pre-eminent women who have contributed hugely to Scottish culture. Ainsley was awarded it for both her glittering academic career (she taught for 25 years at Glasgow School of Art, including five years on the school’s renowned environmental art course) and her artistic practice, the latter becoming Ainsley’s focus after retiring from teaching in 2005.

Currently Ainsley has a solo show at Comar, the ‘multi-arts’ organisation perched on a hill overlooking Tobermory Bay in Mull. This is the her first solo show in Scotland for 30 years – the last being Why I Choose Red at the Third Eye Centre (now CCA) in Glasgow in 1987. Many will wonder why Ainsley didn’t decide to do something sooner. 'The simple answer is, I didn't decide not to, I was never asked,’ she says. ‘Last year I mentioned to Jenny Brownrigg (curator at GSA) that I would love to show my work on one of the Scottish islands and she put me in touch with Mike Darling at An Tobar and it all began from there after a studio visit. I am very thankful that Mike took the time to familiarise himself with my work; so few people are interested in artists in their sixties . . . most of the focus (quite rightly) is on younger or emerging artists but it's lovely to be invited at an advanced age!'

There are 45 new works, large and small, in Ainsley’s exhibition at Comar, none seen before and all created in the last year, in what has to be one of the artist’s most prolific creative periods. The paintings show no sign of an artist in her later years slowing down. Aside from the sheer quantity of work, the paintings themselves are full of energy and buzzing with ideas, moving between shapes and forms. In one, an outline of a tree transforms into a pair of lungs, in another, arteries of a heart become a map of an island. Even the viewer moves, as their perspective shifts through multiple vantage points, from what Ainsley describes as ‘the microscopic, the lens, the atom, to the earth from above, the island, the world and so on’. The works reflect her infectious enthusiasm for the world around her and the easy connections she seems to make between what others may view as disconnected ideas and forms. The paintings are hung in sequences and grids across one wall of the gallery highlighting their ‘network of connections’.

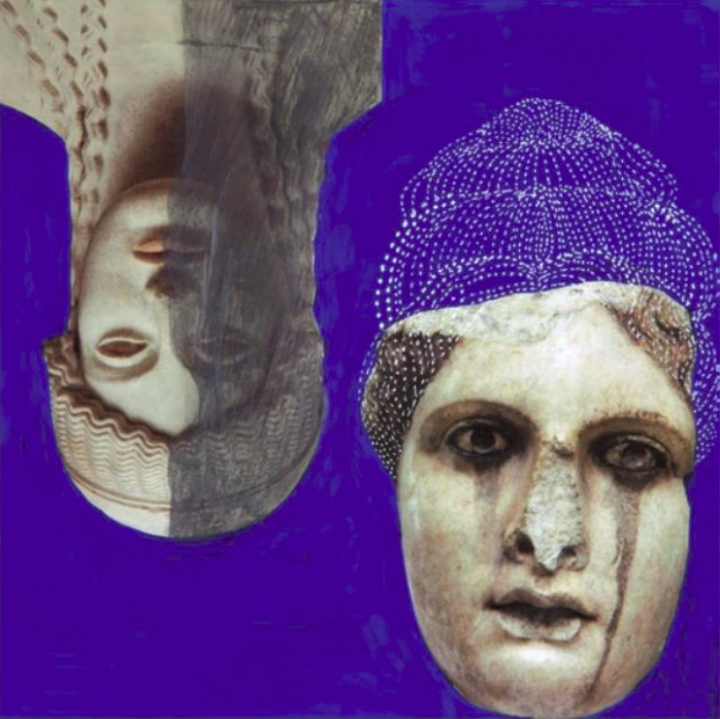

Sam Ainsley, Athena, 2017. Image courtesy of Comar, 2017.

Sam Ainsley, Athena, 2017. Image courtesy of Comar, 2017.

‘I start with an idea of what I want "to talk about" so it might begin with a found image that has excited me or a drawing I've made and then it continues from there; all the time I am conscious of how difficult it is to really convey what it is you are getting at, except obliquely,’ explains Ainsley. Even when discussing her making process, she makes references elsewhere: ‘I'd like to quote the words of Alasdair Gray in Lanark – a huge influence on me: "I started making maps when I was small, showing places, resources where the enemy and where love lay. I did not know Time adds to land. Events drift continually down effacing landmarks, raising the level like snow. The arts are maps. They show us the terrain of life, contours, cliffs and coasts. They chart our deepest oceans and their rivers run like arteries across arid plains.”’

The quote particularly resonates with a five metre-square wall drawing Ainsley has created on site at Comar, with three imaginary islands created alongside a map of Mull that she has turned upside down; ‘I wanted it [Mull] to appear as strange or unrecognisable to the viewer as the other islands,’ Ainsley explains. ‘They all reference different kinds of Utopias based on a huge number of influences over the years . . . suffice it to say that Madeleine de Scudery's ‘Map of Tenderness’ has always intrigued me, where she substituted geographic information with the trials, pitfalls and beauty of love. Metaphor is at the heart of my work, so I loved naming geographic locations in the wall drawing such as the River of Love, the Plains of Indifference, Mount Strife – some of which are hers, some mine.’

‘I have been thinking about utopias and dystopias more recently and islands in particular as places of both refuge and, paradoxically, isolation from a mainland; potentially utopian and dystopian,’ continues Ainsley, ‘and especially in relation to Brexit and Trump, of course . . . ’

That’s what makes Ainsley and her work so captivating – in one moment she’s drawing out imaginary Islands, the next she is very much back to reality, speaking just as emphatically about politics and current affairs: ‘With the Westminster Government, the rise of the far right, Trump in the US, wars everywhere, North Korea's madman to contain, Brexit and more . . . I still believe things can get better, but my God, we are all going to have to be on our guard. In the words of Alasdair Gray (himself quoting a Canadian poet I believe), "work as if you live in the early days of a better nation”.’

Art may offer Ainsley an imaginative retreat from today’s realities, into the utopian landscapes she creates on her canvases, but she equally sees the arts as a means to tackle these issues head on. ‘In dark times, the arts are more important than ever,’ she insists. Which explains her frustration at the future direction the arts are taking in Scotland. ‘I wouldn't start with A Cultural Strategy from the Government and Creative Scotland for a start – Christ, how many times have we been there before to no avail?’ she says. ‘I was on the Scottish Arts Council for many years back in the 80's and it was much, much better than its present incarnation for the simple reason that it had artists on all its decision-making committees. Have "the powers that be" learned nothing? Anything that is top-down will never work. The impetus and ideas have to come from the grassroots; the artists, makers, writers, poets, musicians. Has anyone ever asked them what they would like to see happen except perhaps for a chosen few?’

Reaping the Whirlwind banner at the groundbreaking exhibition 'The Vigorous Imagination', at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art in 1987. Ⓒ The Artist. Courtesy Hugh Watt and John McCann.

Reaping the Whirlwind banner at the groundbreaking exhibition 'The Vigorous Imagination', at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art in 1987. Ⓒ The Artist. Courtesy Hugh Watt and John McCann.

It’s not hard to see why Ainsley thrived as a teacher at GSA; she is a fearless but fair critic, far more focused on nurturing the next generation of artists and ensuring they have a platform than playing by ‘the rules’. However, when Ainsley was teaching alongside David Harding on the legendary environmental art course from the early 80s to the late 90s, there were few rules to follow. ‘Without wanting to sound as if everything was brilliant in the "good old days", the “managers” at the time trusted teaching staff to deliver the best possible experience and education to our students and we did just that,’ explains Ainsley. ‘There was no interference and no sense of being judged or monitored; we were trusted to give 100% to our students and everyone of them was given the time and attention to develop as a potential artist and encouraged to "dream big". The likes of Douglas Gordon, Christine Borland and Roderick Buchanan all studied on the course.

‘I know that many staff now feel they are overworked and have low morale due to the increased amount of paperwork, increased student numbers and decreasing numbers of teaching staff but that's due to Government policy,’ she continues. ‘Nevertheless, GSA is fortunate to have a group of amazing tutors in fine art who do their damnedest to provide the kind of world-class education GSA has been renowned for, despite the difficulties.’

Unlike her salubrious paintings at Comar, the picture Ainsley paints for the Scottish art scene today is a grim one – but one the arts community must confront if things are to change. ‘Culture and all the arts, but visual art in particular, are simply not as valued as they are elsewhere,’ concludes Ainsley, unafraid to point out when things aren’t good enough. She may have stopped academic teaching, but Ainsley’s passion and commitment to the arts is a lesson to us all – and it seems she is not yet done with inspiring those she meets to ‘dream big’.

Exhibition runs until 25 November 2017. Comar. Druimfin, Tobermory, Isle of Mull, PA75 6QB. T: (0)1688 302211 ı comar.co.uk. Open: Tuesday to Saturday 10am–5pm.