Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

Robin Philipson is the 'Modern Master' in focus at The Scottish Gallery

By Susan Mansfield, 24.02.2025

The Scottish Gallery’s Modern Masters series of exhibitions, now in its eighteenth iteration, is a welcome chance to see groups of works by important Scottish artists in the context of a vibrant mixed show. Modern Masters XVIII features works by Joan Eardley, Pat Douthwaite, Wilhelmina Barns-Graham and James Morrison, to name just a few.

However, each show has a focus on one artist around whom the other works orbit, in this show, Robin Philipson, a painter whose work defies easy definition, but whose influence on Scottish painting extends well beyond his lifetime.

Born in 1916 in Broughton-in-Furness in Cumbria, he moved with his family to Scotland when he was 14 and finished his education in Dumfries. He studied at Edinburgh College of Art from 1936-40, and after wartime service with the King’s Own Scottish Borderers, he returned to ECA to teach in 1947.

In her book, Robin Philipson, art historian Elizabeth Cumming writes that he “can be considered to have been the most successful figure in Edinburgh art establishment in the third quarter of the twentieth century”. His roles as teacher - he was Head of Drawing and Painting at ECA from 1960-82 - and as President of the RSA for a decade mean that his influence on art in Scotland extended well beyond his death in 1992.

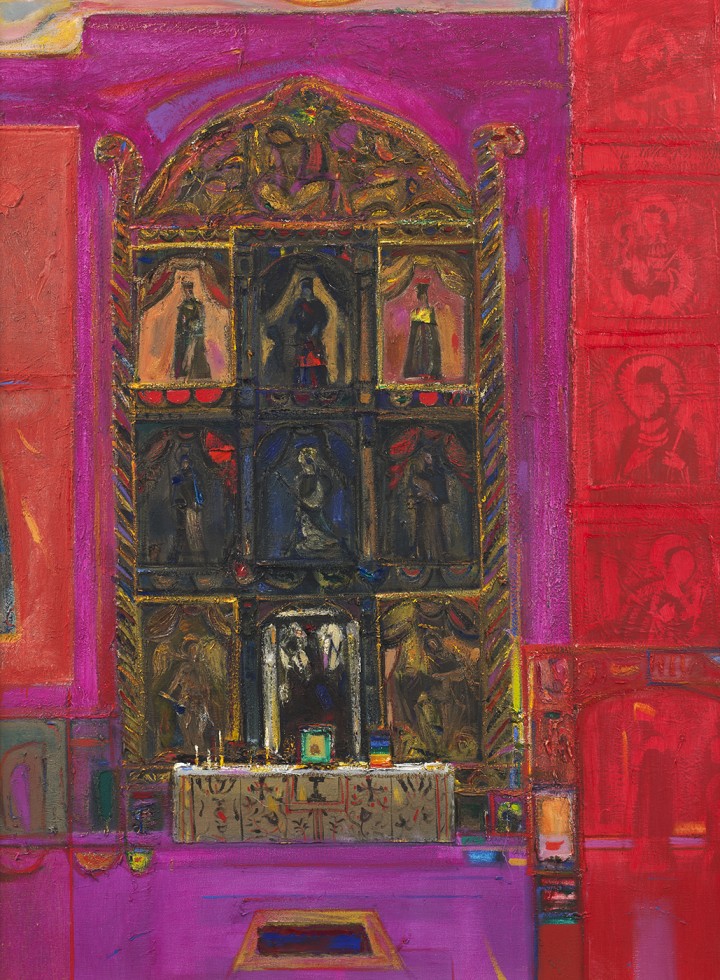

Robin Philipso, 'Mexican Altar', c.1978. Courtesy of The Scottish Gallery

Robin Philipso, 'Mexican Altar', c.1978. Courtesy of The Scottish Gallery

The paintings by Philipson in Modern Masters XVIII are indicative of his range as an artist. The resplendent large work, ‘Mexican Altar’ (1978), is an example of an important Philipson subject: cathedral interiors. This one is a riot of expressionist colour in reds and pinks, in which he plays with depth and scale.

An early work, ‘Nautch Girls’ (1942), was likely inspired by his time posted in India during the Second World War. The dance it depicts was a Mughal tradition which became sexualised during the Raj and associated with prostitution. His circle of dancers echoes the dancers of Matisse.

Robin Philipson, 'Bathers', c.1970. Courtesy of The Scottish Gallery

Robin Philipson, 'Bathers', c.1970. Courtesy of The Scottish Gallery

Colour is the predominant feature in this group of works, from the luminous blue of ‘Bathers’ and ‘A Talk in the Afternoon’ (Edinburgh-based paint manufacturers Craig & Rose mixed a shade they called ‘Philipson Blue’ for him) and the greens and yellows of ‘September Afternoon’, a pastoral scene of figures and animals. Some of his best-known works depict of cock fighting, in which he used expressionist brush strokes to capture the energy and brutality of the birds. A strand of his work explored violence and its aftermath, from dead birds to fallen soldiers, however he was also, as Elizabeth Cumming writes, “one of the most lyrical painters of his generation”. His techniques range from strong colours and heavy impasto to more restrained and descriptive work and luminous watercolours.

Philipson was an important member of the Edinburgh School, which started to form at ECA in the interwar period, where the teaching staff included William Gillies, William MacTaggart, John Maxwell and Anne Redpath, and crystallised in the post-war years. Having been taught by many of these artists, Philipson drew on their influence as well as on European expressionism, particularly Kokoschka, and American abstract expressionism.

The influence of the Edinburgh School is apparent on the next generation of painters, particularly those who trained at Edinburgh College of Art. The discipline of drawing, the importance of the life room, the use of non-naturalistic colour and the creation of works which artist James Cumming described as “visual images of sensuous experience” can all be seen, to greater or lesser degrees, in painters such as John Bellany, Alexander Moffat and Barbara Rae.

In the words of the artist James Cumming, the Edinburgh School was “humanistic in style and figurative in outlook”, all of which could be used to describe Philipson’s own work. Elizabeth Cumming wrote of him as having “a mature commitment to the pictorial: abstraction, where present, never dislodges representation of the world about us”. She concludes: “However we see his art, its free handling, its meaningful decorative values and its sometimes dark subjects, it remains a serious investigation of life.”

Modern Masters XVIII is exhibited at The Scottish Gallery until 1st March