Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

Reminiscences of Anne Redpath and her world in Edinburgh

By Mary Miers, 08.09.2023

Mary Miers (MM): I’m interested in the artistic and musical circle that Anne Redpath and your parents moved in and wondered if you could tell me a bit about that world you grew up in?

Lizzie McDougall: It was Edinburgh in the 1950s, so I was a small child for a lot of these memories. We’d moved north from Buckinghamshire in 1952 and the main thing to point out was that Edinburgh was a very different place to what it is now. It was soon after the War; there was a lot of poverty and greyness. My father had totally Scottish blood, but my mother was initially unhappy to be taken away from her family in the south. She was the daughter of a Welsh minister and as a teenager had played the organ and run the Three Valleys Choir.

MM: So she was already in the music world?

LM: Yes, she was a wonderful musician. She went to the Royal School of Music and the Royal College of Music and studied under Vaughan Williams, whom she adored. In Edinburgh, she soon got into the music world. I remember being pushed in a pram to the National Gallery to go to the lunchtime concerts, which is where I think she met Ellen Kemp, an intelligent and interesting woman. Ellen was a mover and shaker; she knew people and got parties going. There were lots of parties. And what I realise now, looking back, is that their energy was about reconnecting after the War.

There was a focus on rebuilding a better world—‘the flowering of the human spirit through the arts’. My parents were really involved in developing the Edinburgh Festival. But my memories are really all around the parties. We lived in the big house in the middle of Ann Street— number 28—and my parents [Gwen (Gwenllian) and Victor McDougall] had lots of cocktail parties, which were the big thing then. They’d get dressed up, they’d all be standing around chatting with their drinks and cigarettes and my role was to take round the nibbles.

MM: Who were the key characters doing interesting things in Edinburgh at that time?

LM: The people I remember were those who spoke to me. My godfather Charles Milligan was an important Edinburgh character who introduced everybody to everybody. When my family moved north, he was so welcoming and friendly. His wife Madeline was French. They were just wonderful people. They lived in Northumberland Street and we’d go to parties there. He was great friends with everybody because he said everybody was his ‘cousin’. Eileen Handling was another friend; she went back and forth to Russia and knew Rostropovitch. And then there was Monty [Compton Mackenzie]. He was a huge character. There’d always be a chair for him at parties and he’d be the only person sitting down (he was quite old by this time). After I’d gone round with the canapes, I’d sit at his feet and he would tell all these wonderful stories.

So we’d go from Ann Street to Northumberland Street to Drummond Place (where Monty lived) to London Street (where Anne lived).

The others I remember well but whose names I can’t remember were the people who ran the Wilson Barratt Theatre Company based in the Dean Village. They were very thespian; they were all ‘darlin’..darlin’.. ’, but who was whose ‘darlin’ ’, I can’t tell you. There were all sorts of things going on obviously way over my head.

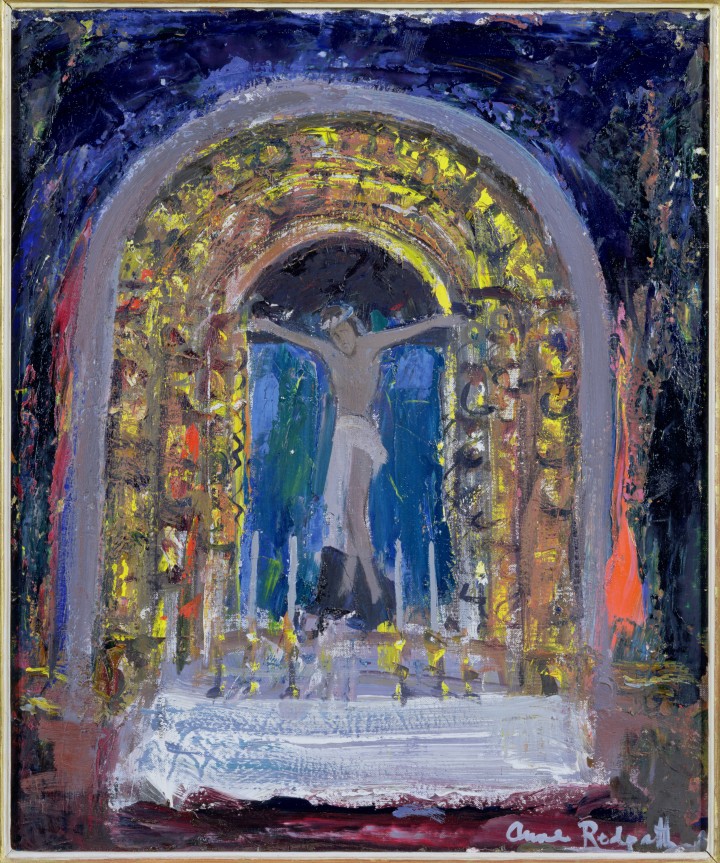

There was also Robin Philipson, who became head of painting at the Edinburgh Art College, and Willie Wilson, who I particularly liked. He had a studio in the Dean Village and I used to go there a lot while he was working.

MM: Anne was born in 1895, so she would have been in her sixties.

LM: Yes; obviously she seemed ancient to me.

.jpg) Anne Redpath Christmas Card Photography by Sunny McDougall Moodie Starlings Studios

Anne Redpath Christmas Card Photography by Sunny McDougall Moodie Starlings Studios

MM: Tell me about her physical appearance. I know some thought she resembled Queen Victoria and in photographs she certainly looks

quite stern. Other reports say that she liked to dress in black, but also that she loved designer hats and dresses. Was she glamorous, or just quirky looking?

LM: What I would say is that she was a bit stout—sort of lozenge shaped— and I think the hats were to give her more height. But obviously she didn’t seem small to me. Without the hat, she always had her hair in a bun. I thought she wore not so much black as a soft, dark French blue or dark emerald green, skirts and jackets with silk blouses.

MM: Can you tell me about her house and what it was like going to see her?

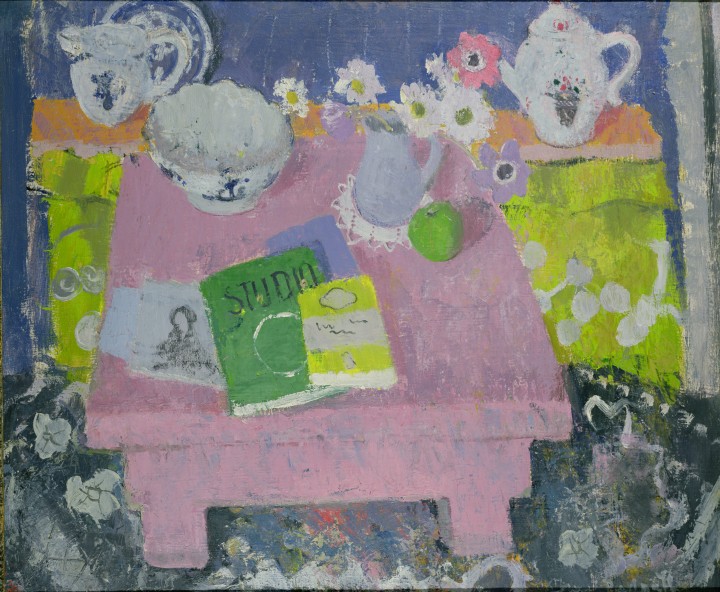

LM: What I remember of her home is being in her studio. It was a big Georgian room in her flat, full of loads and loads of paintings. It was dark, but the paintings were just absolutely glowing with colour. As I was saying earlier, Edinburgh was drab—mostly black and grey, and there was also a dark green that a lot of things were painted. But in Anne’s paintings there was glorious colour. I remember deep, almost purply reds. And wonderful combinations—a large squeeze of a yellow mustard, a soft turquoise and a rose pink. And then there were all the squidges of her oil paints squeezed onto her palette, where there would be old paint that had dried—she just squeezed more on top. The intensity of colour, the smell, just being there: I was transfixed.

MM: do you think it played a part in you becoming an artist?

LM: Oh, a hundred percent. Totally!

MM: Was she friendly to you or quite distant and scary?

LM: She was very nice to me, but I was in awe of her. She

had this aura about her. Another thing I remember is her voice. It was quite different sounding and I just assumed she was French—perhaps because Madeline was French and they used to go to this restaurant called the Aperitif.

MM: She and your mother were obviously close friends. One thing they had in common was that they both had a religious upbringing. Clearly when Anne was living in France she was somewhat rebelling

against her strict Borders childhood; perhaps in Edinburgh she was trying to recreate something of the colour and cosmopolitan lifestyle of the Mediterranean?

LM: Yes. And there was something else: Anne and my mother enjoyed cooking. The cultural norm in Scotland in the 1950s was that it was sinful to enjoy or make a fuss about food, whereas Anne and my mother both really enjoyed discussing it. I remember lots of casseroles with wine, bay leaves and bouquet garnet and Beef Stroganoff, with its story of the Russians. Beef strips sautéed in garlic and butter with added cream and white wine to make a sauce, served sprinkled with chopped parsley. New potatoes (scrubbed not peeled) with butter and chopped chives and a green salad with French Dressing. Most important was the French Dressing, made with olive oil, wine vinegar, garlic crushed with a little salt and sugar and French mustard. These ingredients, and other lovely things, could only be found at Valvona and Crolla at the top of Leith walk near Anne’s flat. Other delights included ‘real coffee’, salamis, French bread and cheeses and olives. Souffles were fashionable. Everyone adored my mother’s lemon souffle; she grated lemon rind on it and it was amazing!

MM: do you remember anything from the final part of Anne’s life?

LM: I remember my mother coming back from the funeral. She was so sad. She’d really lost this light of a friend, but then it transpired she was also upset because she felt Anne wasn’t respected enough as an artist. It was still very much a man’s world then, even in the art world.

Lizzie McDougall was accepted at the Edinburgh College of Art at the unprecedentedly young age of 16 and studied drawing and painting. She then worked on the lighting for the Lindsay Kemp Dance Co, often visiting his basement flat in Drummond Street, where Davey Jones (Bowie) and his girlfriend Angie slept on a small bed in the kitchen. She is now a storyteller and artist living and working in the Highlands.

The Fleming Collection exhibition Anne Redpath and Friends is showing at the Granary Gallery in Berwick Upon Tweed until 5th November