Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

Remembering Janet Boulton at Little Sparta

By Greg Thomas, 28.02.2024

The artist Janet Boulton, who has died at the age of 87, was a painter and gardener whose wide oeuvre includes remarkable sequences of watercolours responding to Ian Hamilton Finlay’s poem-sculpture garden, Little Sparta.

I visited the artist Janet Boulton in October 2023, shortly before her death, to talk about her creative relationship with Ian Hamilton Finlay for an ongoing project commissioned by the Fleming Wyfold Foundation. As we sat in the top-floor bedroom-cum-art storage area of her townhouse in Abingdon, Oxfordshire, she pointed out that she had “undertaken a substantial apprenticeship” before making her first works in response to Finlay’s garden at Stonypath (also known as Little Sparta) in the Pentland Hills south of Edinburgh. Boulton’s framed paintings of the garden and its environs were laid out in rows in front of us as we spoke, windowsills and shelves populated with model boats, some made by the same craftsman who built them for Finlay.

Contextualising the remark just offered, Boulton (who was born in Wiltshire to a farming family) explained that “I’d been painting and drawing gardens for about ten years before I came to Little Sparta.” Over the decades, she worked especially closely in response to five. “The first was just a small back garden in Oxford that I found utterly fascinating.” From there, her studies took her to the Rosemary Verey’s garden at Barnsley House in Gloucestershire and then to the grounds of the Villa La Pietra in Tuscany (along with other Italian gardens). “Then I moved on to Little Sparta, and I ended up at the Cow Mead Allotments in Oxford.”

Janet Boulton, Kitchen Garden with Lemon Trees villa La Pietra, image courtesy of the artist's estate

Janet Boulton, Kitchen Garden with Lemon Trees villa La Pietra, image courtesy of the artist's estate

“I first met IHF on 2 July 1993,” Boulton had informed me by introductory letter prior to my visit—though she had known his work since the mid-1980s. During that first trip north, “I asked if he would allow me to make drawings of the garden...he understood my firm objective in seeing the garden in winter (structure/terrain) although it is not open at this time.” Finlay saw the garden as only truly existing during the summer months, yet he allowed Boulton access all seasons, an “extraordinary concession,” according to writer and fellow Finlay collaborator Patrick Eyres (Remembering Little Sparta [2009])—and a sign of great creative respect. Picking up the thread during our interview, Boulton recalled that “for some reason, which I still can’t explain, Ian felt entirely comfortable with me and I with him. I didn’t think it would be possible, at first, to spend long enough there to paint it properly....But he made it so easy for me.”

In his preface to the accompanying text for Remembering Little Sparta, a 2009 exhibition of Boulton’s work held at Edinburgh College of Art, Eyres explains that the painter would visit for week-long stretches twice every 18 months.i (Her travels were partly governed by the school year, as she had become a teacher following her art-school days in Swindon and Camberwell). Work was undertaken en plein air except when forced inside by truly dreich conditions. Sometimes easels would have to be tied to trees or secured in the ground as a bulwark against the wind. Eyres offers a useful sweep of historical precedents for the extensive body of work that resulted from these spells at Stonypath. “Ever since the emergence of watercolour landscape as an artistic genre in England, painters have been attracted by the classical garden; think of Cozens in Rome, Cotman at Rokeby or Turner at Petworth.” But interior scenes were central to Boulton’s work at Stonypath, too, including pictures of model boats, which were often arranged on windowsills in the Finlay family home. (Ian published some of these as cards, including Sparrow, A Seychelles Stradivarius, and French Sardine Lugger [all 1996].)

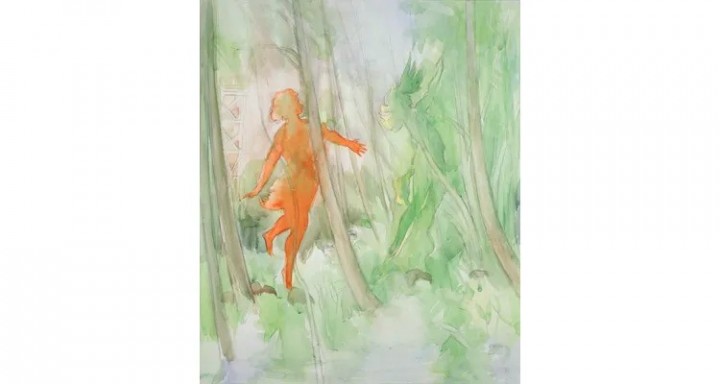

Janet Boulton, Apollo and Daphne, Little Sparta, image courtesy of the artist's estate

Janet Boulton, Apollo and Daphne, Little Sparta, image courtesy of the artist's estate

That qualification aside, Janet’s varied responses to the Roman Garden – a foliage- enclosed, house-front enclave of Little Sparta, with six stone sculptures depicting miniature, abstracted versions of World-War-Two military craft or their components – are typical of that wider body of work in their verve and variety. Finlay’s statues, each perched on a plinth, collectively entitled Homage to The Villa d’Este and carved by John Andrew, stirred memories of Boulton’s time at the namechecked sixteenth- century Italian garden. Indeed, the garden includes a similar, stylised sculpture of a ship, in the Fontana do Rometta.

Boulton ultimately produced five sextets of Roman Garden-themed works, including a set of imposing front-on images in 1997, in which each stone-carved form is shown in its milieu of potted hosta plants. The flattening of perspective, use of visible pencil lines, and pale ochre colour-planes used to pick out plinth and statue, suggests the influence of Cezanne, an artist Boulton repeatedly referred to as a source of inspiration. The teal and terracotta of the enveloping leaves and pots, meanwhile, were chosen, she told me, to “match the colours you’d see in Roman wall paintings....I wanted the sequence to have that sort of monumental, slightly detached air that classical art can have.”

Paper-pulp relief works were also made in response to the Roman Garden, more vibrantly coloured than the watercolours and produced using a unique method devised by the artist. These pieces have something of the rough, pop-collage feel of Jasper Johns, say, though the project was “spurred on,”Eyres notes in Remembering Little Sparta, “by the mutual interest of painter and poet in the Cubist collages invented by George Braque.” Boulton also made abstract foamboard maquettes using motifs from Finlay’s garden-within-a-garden, ideally intended for realisation in marble.

Many other pieces from Boulton’s Little Spartan period deserve deep scrutiny, including her stark yet oddly emotionally charged paintings of Finlay’s Japanese Stacks maquettes (the basis for his 1978-79 laminated-wood sculptures); her paintings of the garden temple interior (which was used to store artworks, and thus has the feel of a sort of holding bay of historical allusions, as Harry Gilonis notes in his essay in Remembering Little Sparta); and her paintings of the wider environs of the garden and surrounding moorland, including stunning pieces in square and exaggerated panoramic formats. Suffice to say, it’s important to emphasise how unique the painter’s relationship with Finlay was vis-a-vis her relative lack of engagement with him as a collaborator: the singular independence she maintained in engaging with his oeuvre.

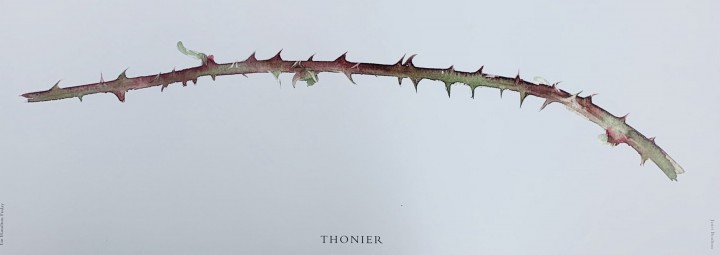

Janet Boulton, Thonier, Image courtesy of the artist's estate

Janet Boulton, Thonier, Image courtesy of the artist's estate

Exceptions to this rule include Finlay and Boulton’s 1999 print ‘Thonier’ (1999) – for which Boulton painted a bramble branch recalling the shape of a fishing rod used for catching tuna or “tunny” – and the photobook ‘Highlights: A Homage To Andre Derain’ (1997). As we discussed these projects, the artist recalled how difficult she had found it attempting to work according to another artist’s ideas. However, she enjoyed adding Derain-esque chalky highlights to tree-trunks for the latter work, ready for Robin Gillanders, the other collaborator on the book, to photograph.

Finlay attempted to initiate more collaborations than were realised, Boulton told me. Indeed, the fact that he ultimately acknowledged his friend’s desire to produce an original body of work in response to his, rather than being set to task, is testament to their bond and to Boulton’s fierce independence of spirit.ii His influence is, nonetheless, borne out in Boulton’s own garden, once a long sliver of grass and paving to the rear of her Abingdon home. Since the 1980s, this space (which I was lucky enough to explore during my visit) has been transformed by planting and landscaping – skills learned during decades of study of others’ gardens – and since 1996 by artworks in wood, glass, and other materials.

Many of Boulton’s methods of placing language in relation to sculptural material and foliage recall Finlay’s poetic universe at Stonypath. But Boulton’s garden also encapsulates her own aesthetic and cultural interests, such as the cubist art she had loved long before the relationship with Ian commenced. Moreover, Janet was able to call on a far greater degree of technical skill as a gardener than was her Scottish peer—she was an expert on ivies in particular.

A piece in wooden lettering to the very back of Boulton’s garden, ML11 8NG, recreates the postcode for the Finlay’s fellside home. In her 2013 book Foreground Background: About Making A Garden, Boulton called this “a reminder and an acknowledgement.” We might also read it as a witty riposte, from someone more at home on dry land, to the fishing-boat port-numbers used in Finlay’s 1960s work. Perhaps above all, the work appeals as coda, or an endnote, to a rewarding period of creative affinity.iii

i This exhibition represented an important summation and consolidation of Boulton’s work in response to Little Sparta. In 2018 her exhibition A Seeming Diversity: Working with Watercolour, at Swindon Museum and Art Gallery, presented a similar survey of her career in watercolour as a whole.

ii An extensive selection of materials related to Janet Boulton’s work at Little Sparta has been available to view since 2021 at Edinburgh University Library’s special collections library.

iii Sincere thanks to Colin Sackett and Harry Gilonis for their invaluable advice and edits on this article.