Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

Postcards from the Front

By Greg Thomas, 28.05.2020

The Fleming-Wyfold Art Foundation’s new acquisition of posters and postcards by Ian Hamilton Finlay offers a window into the oeuvre of an artist forever at war, says Greg Thomas.

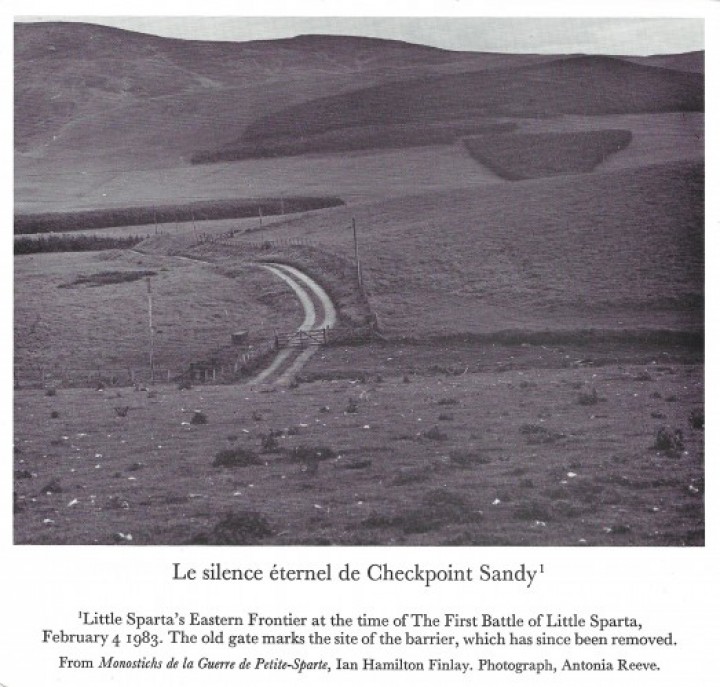

One of the card and paper-based works newly acquired by the Fleming-Wyfold Art Foundation, produced by Scottish poet, artist, and gardener Ian Hamilton Finlay during the 1980s and 1990s, shows a wooden gate nestled between two folds of farmland. This is Checkpoint Sandy, ‘Little Sparta’s Eastern Frontier at the time of The First Battle of Little Sparta, February 4, 1983’. This ‘battle’ took place when Strathclyde Regional Council sent a sheriff’s officer (named Sandy) to seize works from Little Sparta, Finlay’s poem-sculpture garden and home since 1966, in lieu of unpaid tax.

The officer was intercepted by a series of intricate parrying manoeuvres, carried out by a group of Finlay’s supporters dubbed the Saint-Just Vigilantes (one flyer from the acquisition implores us to ‘Join the Saint-Just Vigilantes’) under the direction of the artist himself, positioned in a hayloft repurposed as command HQ. The whole affair was meticulously documented and photographed, and an illustrated report was published in a literary magazine. Besides throwing up a slew of polemical and satirical ephemera, the ‘battle’ was honoured by a commemorative medal and a bronze plaque now mounted on a wall marking the garden’s entrance.

Ian Hamilton Finlay. Le Silence Eternal de Checkpoint Sandy, 1986. © The Estate of Ian Hamilton Finlay.

Ian Hamilton Finlay. Le Silence Eternal de Checkpoint Sandy, 1986. © The Estate of Ian Hamilton Finlay.

The story of the Checkpoint Sandy postcard offers a glimpse into the principles animating Finlay’s whole practice by the early 1980s and across the subsequent decade: the period to which the majority of this work can be dated. It also reminds us that eulogies for this most trenchant of Scottish creatives should be attempted with caution.

By the early 1980s, Finlay had moved through the late-modernist aesthetics of concrete poetry – the presentation of language as visual form – to a more expansive multimedia practice in which word and image were combined across a range of media, from poems etched in wood and glass to inscribed sculptures and statues set in mutually illuminating relationships with landscapes. More significantly, Finlay no longer viewed his poems, or artworks, as self-contained entities, but as monuments to an ideal of formal, moral, and rational order that was to be physically manifested in the garden. His two-dimensional works were documents of a process of world-creation, one that often brought him into conflict – both theatrical and painfully real – with the world beyond the garden gate. Finlay rarely saw this world, confined by agoraphobia to Little Sparta from the late 1960s onwards.

The notion of an avant-garde artist setting his stall out against the organs of state bureaucracy is perhaps a gesture we are relatively 'au fait' with. What modern audiences might find harder to handle is the fact that these rebellions were not undertaken from some position of radical egalitarianism or anarchism but from a basis in spiritually invested social conservatism that stood radically at odds with the liberal consensus of the era. The war around tax had erupted because Strathclyde Region refused to accept that the ‘art gallery’ (as they saw it) on Little Sparta’s grounds was, as Finlay would have it, a temple, where certain spiritual truths were incarnated, and which was therefore due the lower tax rates afforded to religious buildings.

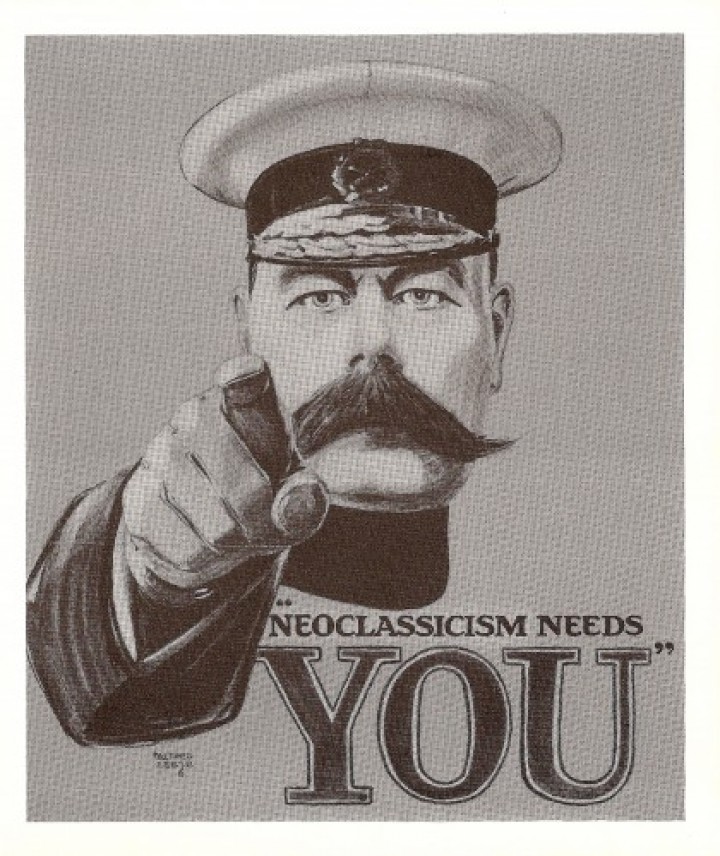

Ian Hamilton Finlay, Neo-Classicism Needs You, 1983 © The Estate of Ian Hamilton Finlay

Ian Hamilton Finlay, Neo-Classicism Needs You, 1983 © The Estate of Ian Hamilton Finlay

Neoclassicism became for Finlay the aesthetic encapsulation of this worldview. ‘Neoclassicism Needs You’, one work announces, mimicking Lord Kitchener’s recruitment posters. Another undercuts a statement attributed to the anarchist modern art critic Herbert Read – In the back of every dying civilization sticks a bloody Doric column – asserting, to the contrary, that ‘In the foreground of every revolution, invisible, it seems, to the academics, stands a perfect classical column’. If the polemic here is infused with a certain sense of whimsy, neoclassicism is elsewhere imbued with the sinister spirit of its most fervent recent proponents.

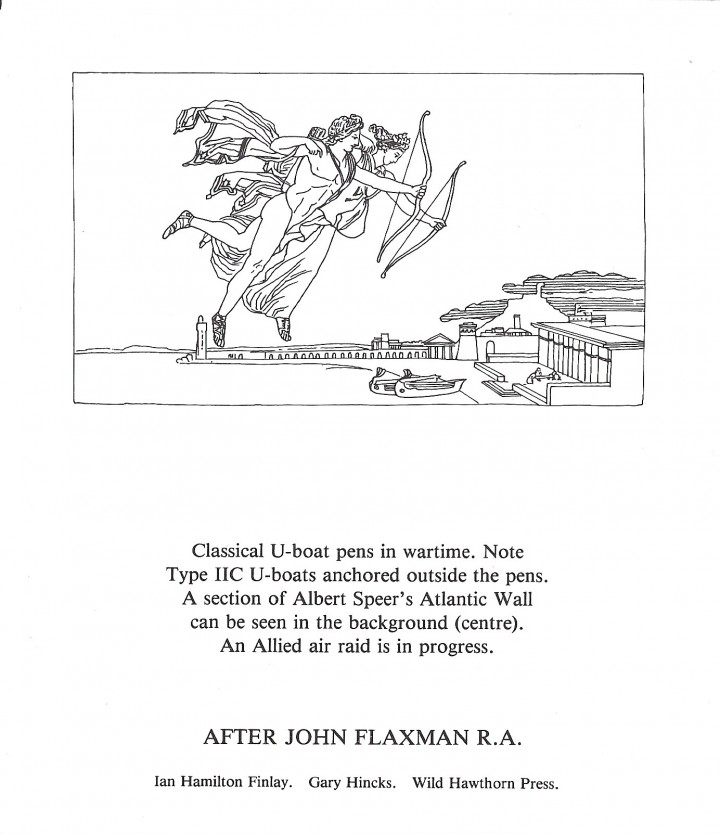

A sketch in the style of the 18th-century English draughtsman John Flaxman shows us ‘Classical U-boat pens in wartime’, with a ‘Section of Albert Speer’s Atlantic Wall’ – the Nazis’ gargantuan coastal defence system – visible behind. Is Finlay endorsing the culture of the Third Reich as the natural extension into society and politics of the neoclassical order he loved? We are certainly invited to suspect this, which of course implies a subtly different authorial motive from straightforward endorsement, one further clouded by the quality of mordant satire that pervades the work.

Ian Hamilton Finlay, Classical U-Boat Pens in Wartime, 1980 © The Estate of Ian Hamilton Finlay.

Ian Hamilton Finlay, Classical U-Boat Pens in Wartime, 1980 © The Estate of Ian Hamilton Finlay.

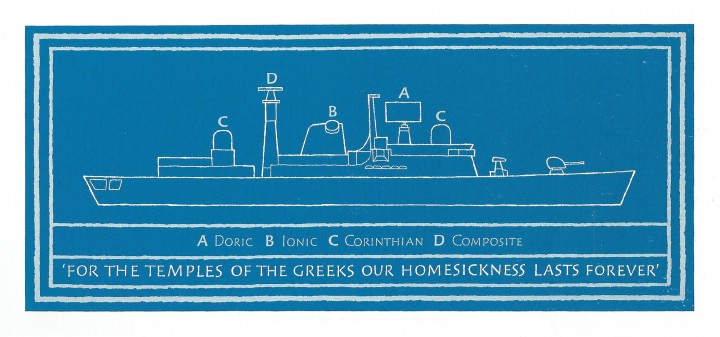

One position that Finlay endorses more clearly is the necessary relationship between defence of aesthetic order and a willingness to impose order, by force if necessary, at a social and political level. Another work shows a segment of classical column morphing over four appearances into a marching drum of the kind used to lead militias during the French Revolution (this also inspired the carving Classical/NeoClassical acquired by the Fleming Collection in 2019). Below, a quote from Saint-Just, the most ardent and bloodthirsty of the revolution’s children – after whom Finlay’s pseudo-militia of civilian supporters was named – assures us that ‘what constitutes a republic is the total destruction of all that is opposed to it’. In another piece, the conning towers and gun-mounts of a WWII battleship are re-envisaged as orders of column from Doric to Composite.

Contemporary admirers of Finlay’s works might find themselves struggling to assimilate such messages and allusions with their overarching sense of fascination and wonder at his creative achievement. This feeling of conflict is invited. These are not works to agree with, but works to be reckoned with, and savoured.