Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

Marine Lights

By Greg Thomas, 06.07.2021

Ian Hamilton Finlay’s Marine, running at Edinburgh’s City Arts Centre until 3rd October, is arguably his first substantial retrospective show in Scotland. Focusing on the maritime and nautical connotations of Finlay’s practice, this selection of work reveals the metamorphosing power of the artist’s vision. Greg Thomas picks out five of the most striking pieces on display—from print and sculpture to toy boats.

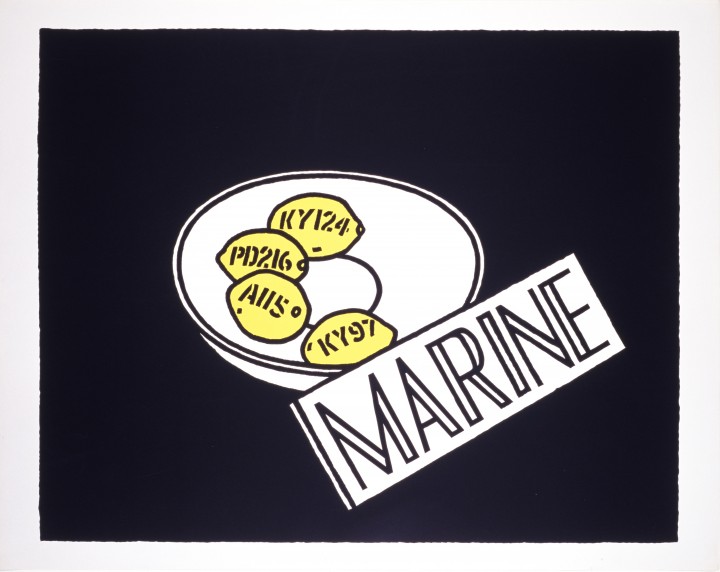

Marine, with Patrick Caulfield (1968)

The exhibition’s title-print exemplifies Finlay’s sense of the metaphorical potential of maritime themes, turning to a well-worn metaphor from across his oeuvre, first used in 1956 in the short story “The Splash,” about two boys trespassing on a fishing boat: “Then we went to the bow, and then, last of all, to the stern. Both ends of the boat were pointed, and in between, as in a lemon, there was squeezed a fat bulge.” In this silkscreen print tenor and vehicle switch places. A set of lemons rests in a bowl, inscribed with port-codes like those printed on the sides of boats, and the jaunty title “MARINE,” in cargo-crate type, affixed to the image. The work is interesting both in showing how Finlay ferried metaphors from one stage of his practice to the next, and also how he was able to make space for another artist’s distinctive style – in this case Caulfield’s pristine pop colour blocks – while simultaneously producing work that was unmistakably his own.

For his 1968 exhibition 'Boat Names and Numbers', Finlay pushed the tenets of concrete poetry to the extreme by creating large-scale painted wooden sculptures that were simultaneously poems. Across the following decade he extended his practice in historically minded and formally adventurous directions, leaving the page-based constraints of concrete behind. But in the late 1970s he returned to the concept of his 1968 show: recreating boat names and numbers as works of colourful minimalist sculpture. Coastal Boy is part of a little gathering of similar pieces in an alcove on CCA’s second floor, forming a mirror image – as it were – of the full-size boat in situ across the way, the 1997 work Wings (with John Andrew). Works such as coastal boy remind us of Finlay’s capacity not only to incorporate visual and three-dimensional forms into a language-based practice, but also to use language to evoke absent objects and environments.

'Marine: Ian Hamilton Finlay' Installation View (5). Photo Lloyd Smith.

'Marine: Ian Hamilton Finlay' Installation View (5). Photo Lloyd Smith.

Toy boats (various)

Finlay’s practice derived its value partly from its overarching scale and scope, ever evolving and expanding through the publication of new cards or booklets from his Wild Hawthorn Press, or new installations sited in his poet’s garden at Little Sparta. Something of the transportive atmosphere of the garden is evoked through a series of photographs by Robin Gillanders (Ian’s Fleet [2002]) showing his toy boats afloat on Lochan Eck, a man-made pond at the rear of Finlay’s grounds. Arguably more captivating still is the selection of little wooden sailing boats, with dowels for masts and coated in thick varnish, spread across the vitrines on the third floor of the gallery. These pieces, amongst the few on display almost certainly handmade by the artist himself, remind us that, for all its trenchant political and cultural connotations, Finlay’s art was motivated by a childlike sense of wonder and play.

Big E (At Midway), with John Andrew (1976/77)

As Finlay’s art developed across the 1970s he became more and more concerned with themes of conflict: from the agonistic worldview of Pre-Socratic philosophers to the battlefields of World War Two. At the root of much of his work is a desire to bring narrative clarity to the violence of twentieth-century history by placing it in the light of classical myth. A talismanic yet evasive work in this sense is Big E (At Midway II), created by stone carver John Andrew, a long-time collaborator. As art historian Stephen Bann notes in the exhibition’s catalogue, this piece, a stone model aircraft carrier with a large E etched into its landing strip, “refers to the carrier, U.S. Enterprise.” However, its title also “directs us to study Plutarch’s essay on the ‘E at Delphi’, which explores the multiple interpretations of a mysterious stone in the Temple of Apollo at Delphi, bearing this single carved letter.” Classical analogy here yields no interpretive clarity, offering only further mystery.

, 'reef-points - manx nobby', 1996. © the estate of ian hamilton finlay. photo - antonia reeve.jpg) Ian Hamilton Finlay (with Gary Hincks), 'Reef-Points - Manx Nobby', 1996. © The Estate of Ian Hamilton Finlay. Photo Antonia Reeve.

Ian Hamilton Finlay (with Gary Hincks), 'Reef-Points - Manx Nobby', 1996. © The Estate of Ian Hamilton Finlay. Photo Antonia Reeve.

Reef-Points, with Gary Hincks (1996)

This dazzling set of screen-prints takes as its underlying visual motif the “reef points” – small, flat pieces of plaited rope – used to tie up sails. For all that Finlay’s art relied on linguistic play and hidden depths of meaning and cultural association, these works remind us of the visual pleasure to be derived from it. In bold, luminous colours vaguely reminiscent of the mid-century serial concretism of Richard Paul Lohse and others, each print is paired with a boat type: Banff Zulu, Campbeltown Zulu Skiff, St. Ives Mackerel Diver, Mounts Bay Pilchard Boat, Manx Nobby, West Country Gaffer, Yarmouth Lugger. This little found poem of names, like the print sequence itself, exemplifies Finlay’s graceful entwining of homely and avant-garde reference-points. When he received his set of prints in the post, Bann recounts, “on a sunny, blustery day,” “the artist ran around the garden holding one of the prints in the air, as if it might serve as a sail!”

, 'reef-points - mounts bay pilchard boat', 1996. © the estate of ian hamilton finlay. photo - antonia reeve.jpg) Ian Hamilton Finlay (with Gary Hincks), 'Reef-Points - Mounts Bay Pilchard Boat', 1996. © The Estate of Ian Hamilton Finlay. Photo Antonia Reeve.

Ian Hamilton Finlay (with Gary Hincks), 'Reef-Points - Mounts Bay Pilchard Boat', 1996. © The Estate of Ian Hamilton Finlay. Photo Antonia Reeve.

Marine: Ian Hamilton Finlay is showing at City Arts Centre until 3 October. Find out more here.