Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

Mackintosh 150

By Susan Mansfield, 01.05.2018

There was an air of anticipation in the room as the crate was prised open. Curators and conservators held their breath as the protective layers of plywood and tissue paper were removed. Inside were sections of wall panelling from Miss Cranston’s Ingram Street Tea Rooms in Glasgow, designed by Charles Rennie Mackintosh, rescued from the building in 1971 when it was turned into a hotel. But had the years been kind to them?

There was palpable relief as the panels were lifted intact from the crate. They had been over-painted by a later owner of the building, but it was still possible to make out traces of Mackintosh’s classic rose stencilling. Now fully restored by Glasgow Museums conservators, they will be exhibited in public for the first time in Charles Rennie Mackintosh: Making the Glasgow Style, a major exhibition running until August at Glasgow’s Kelvingrove Art Gallery & Museum.

The exhibition, which is the first major Mackintosh show in the city since 1996, is a linchpin in Mackintosh 150, a year-long programme of events to mark the 150th anniversary of the artist’s birth. Mackintosh partners including The Hunterian, Glasgow School of Art, the Lighthouse and the Charles Rennie Mackintosh Society will organise their own programmes. Meanwhile, another Mackintosh treasure, the Oak Room from the Ingram Street Tea Rooms, will be a key attraction of the Scottish Design Galleries at the V&A Dundee when it opens in September.

F Macdonald, M Macdonald, Mackintosh & J Herbert McNair. Glasgow Institute of Fine Arts. Glasgow Museums.

F Macdonald, M Macdonald, Mackintosh & J Herbert McNair. Glasgow Institute of Fine Arts. Glasgow Museums.

The Kelvingrove exhibition tells the story of Mackintosh’s life and his circle through over 250 objects including stained glass, ceramics, metalwork, furniture and architectural drawings, many of which have rarely been exhibited publicly. Highlights include The Seasons, a set of four watercolours created by Charle’s wife Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh and her sister Frances, rare paintings from Mackintosh’s late period, architectural plans from Scotland Street School and Glasgow School of Art and Margaret’s iconic panel The May Queen.

Curator Alison Brown of Glasgow Museums says she is keen to show the context from which Mackintosh emerged. ‘It’s very important for me that he’s not an isolated genius. He is a genius, but he’s part of a really amazing creative time of development in Glasgow. This is the period when Glasgow was the second city of the empire, it must have been a very exciting time.’

Charles Rennie Mackintosh was born in 1868 in Townhead, the fourth of eleven children. His father was a police superintendent. He was educated at Allan Glen’s technical school and became an apprentice architect with local firm John Hutchison, taking evening classes at Glasgow School of Art. It was here he fell into the orbit of the charismatic head of school, Francis Newbery, and where he met the friends who would become known collectively as The Four: James Herbert McNair and sisters Margaret and Frances Macdonald, whom the two men would marry.

The group were at the heart of what became known as the Glasgow style – the city’s own take on art nouveau – at a time when Glasgow School of Art was a powerhouse both for the decorative arts, with its newly opened Technical Art Studios, and female emancipation. This was the age of the Glasgow Girls, among them women such as Jessie M King, Ann Macbeth and Dorothy Carleton Smyth.

Brown says: ‘The exhibition looks at the Technical Art Studios, who taught there, who studied there, the work they went on to produce. I’ve selected things which show the process of making, because I want people to make the connection between Mackintosh and that working process.’

Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Chair for Hill House. Glasgow Museums.

Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Chair for Hill House. Glasgow Museums.

The exhibition offers a chance to follow the development of Mackintosh’s ideas from early watercolour and poster designs, done while working as a junior draughtsman with architects Honeyman & Keppie, through to complete designs for interiors and private homes. His passion was for the ‘gesamtkunstwerk’ or ‘total work of art’: in his tea rooms, for example, he specified the design of the teaspoons as precisely as the chairs or the windows.

By 1904, the year Mackintosh was made a partner at Honeyman & Keppie, his vision was in full flight. He was working on the Ingram Street and Willow Tea Rooms for Miss Cranston, as well as interiors for her home, Hous’hill, and was putting the finishing touches to the Hill House, built for publisher Walter Blackie in Helensburgh. He was also working on Scotland Street School.

Brown says that in this period Mackintosh began to depart from art nouveau and the Glasgow style and pursue geometric designs of his own. ‘Over that period he really starts playing around with squares, which become dominant. I’m wanting to communicate how early on Mackintosh moves into art deco – before it was known as such. He becomes obsessed with geometry, it’s an absolute distillation of forms and lines.’

In his white, uncluttered interiors, Mackintosh departed radically from the often dark and highly decorative interiors of the 19th century, prefiguring what would be known later as ‘modernism’. Brown says: ‘Mackintosh is regarded as a pioneer of modernism for his approach and his simplicity. However, what I think he’s so good at is that he’s a magpie. He sees things that work, and he distills them. He distills Scottish vernacular architecture, ideas from Japan and nature, he fuses these things together and creates something really unique.’

Meanwhile, a living example of the Mackintosh ‘gesamtkunstwerk’ is currently being restored on Sauchiehall Street. Mackintosh at the Willow is an ambitious £10million restoration of Miss Cranston’s Willow Tea Rooms, scheduled to open in June in time for the 150th anniversary. Celia Sinclair, chairperson of the Willow Tea Rooms Trust, says: ‘This is one of the only complete pieces of Mackintosh’s work that exists now, the only tea room where he designed both the interior and exterior. We are aiming to recreate the tea rooms as they were in 1903 when they were handed over to Miss Cranston. It was very, very modern for its time, and now it’s coming back together we are realising it’s very modern now.’

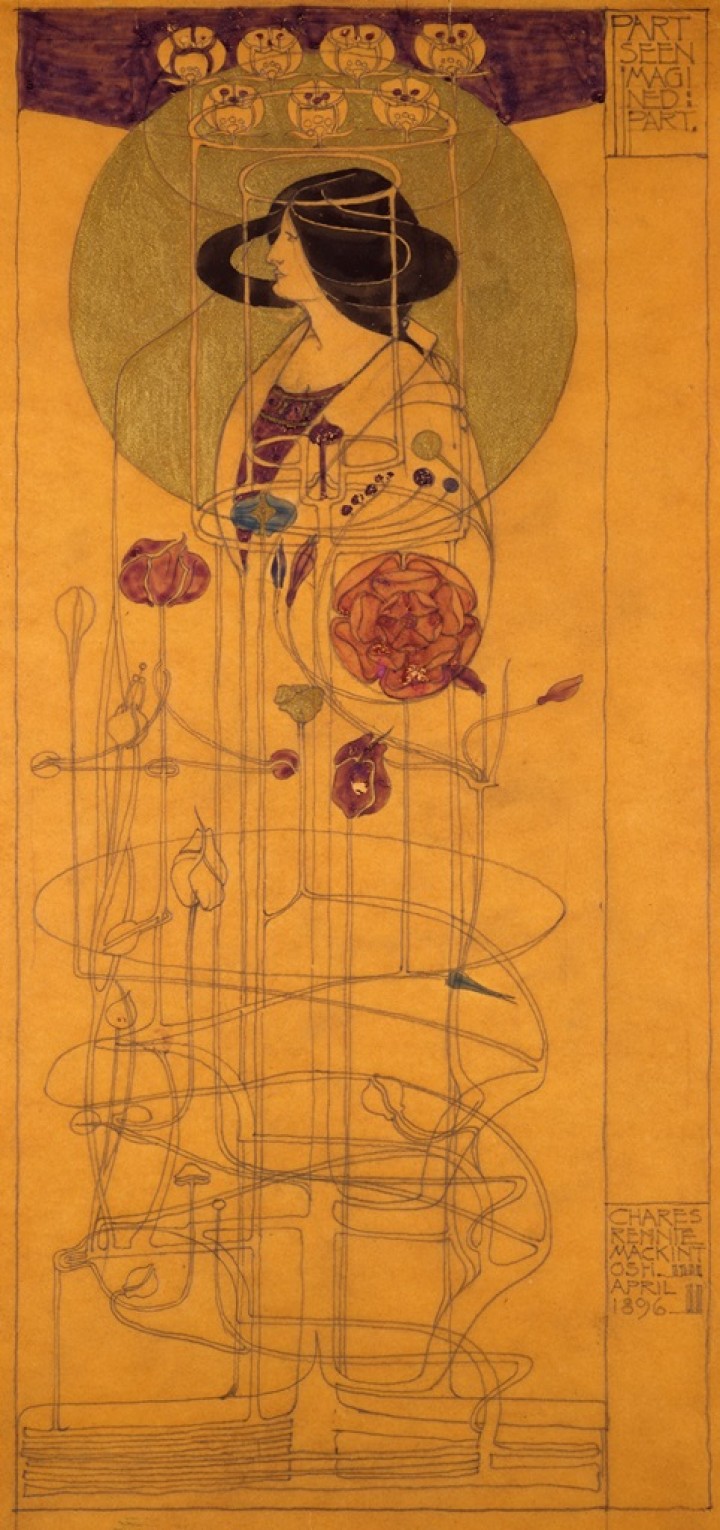

Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Part Seen Imagined Part. Glasgow Museums.

Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Part Seen Imagined Part. Glasgow Museums.

The Trust was able to purchase the building (which had fallen vacant) in 2014, along with the building next door, which will house modern visitor facilities, conference and education rooms, an exhibition and shop. Every aspect of the tea room restoration has been scrutinised by a panel of experts, from the lighting to the table cloths, the teaspoons to the carpet designs. The window of the Salon de Luxe, which was moved nine inches inwards in the 1980s, has now been moved back out to its original position. Objects too valuable to be used – the glass doors from the Salon de Luxe currently valued at £1.5million – will be shown in a museum area, with exact replicas made for the tea room.

Sinclair is in no doubt of the pulling power of Charles Rennie Mackintosh both in terms of drawing overseas visitors to Glasgow and for enthusing the city’s own residents, who have embraced him as one their most famous sons. ‘We realised the level of interest when we closed the building down. There were so many visitors trying to get into the project office that we opened a pop-up information point. In 26 working days we had 2700 people, 60 per cent of them from 40 different countries. All of them had come to see the tea rooms. There’s huge interest in this project from all over the world.’