Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

Loved Ones in the Fleming Collection

By Alice Strang, 08.06.2020

Living under lockdown means many of us are spending more time than usual with loved ones at home, whilst the easing of restrictions means we can see those beyond our households after months apart. We look at how artists have portrayed those closest to them in works in the collection.

Eástre (Hymn to the Sun) by John Duncan Fergusson (1874-1961) is believed to be a portrait of his partner, the dance pioneer Margaret Morris (1891-1980). They met in 1913 when Morris travelled to Paris with her troupe and presented herself at Fergusson’s studio. Thereafter their personal and professional lives were intertwined until Fergusson’s death in 1961. Respecting each other’s independence, the couple never married, deliberately did not have children in order to focus on their callings and did not live together until the outbreak of World War Two forced them to settle in Glasgow in 1939.

The sculpture’s title refers to Eástre, the Saxon goddess of Spring and to Morris’s performance ‘Hymn to the Sun’, inspired by the music of Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1844-1908). For Fergusson, Morris was the embodiment of the emancipated modern woman, who was also in touch with ancient forces through the rhythms of dance. The simplified, flowing forms of the highly-polished sculpture embody those qualities in three-dimensions. Fergusson’s most celebrated sculpture, he originally made it in plaster in 1924 and kept it under his bed for three years before he could afford to have it cast in brass. Posthumous editions were made in 1971 and 1991-92.

Cecile Walton (1891-1956), Early Morning, 1922 © The Artist’s Estate / Bridgeman Images

Cecile Walton (1891-1956), Early Morning, 1922 © The Artist’s Estate / Bridgeman Images

Cecile Walton’s Early Morning of 1922 celebrates motherhood, in this case her relationship with her younger son Edward. Walton met her first husband, the artist Eric Robertson (1887-1941), when they were students at Edinburgh College of Art. Despite the disapproval of her parents, the artists Helen Law (née Henderson, 1859-1945) and Edward Arthur Walton (1860-1922), they married in 1914 (and divorced in 1927). Their first son, Gavril, was born in 1915 and Edward four years later.

In the painting, a recent addition to the Fleming Collection, Edward is seen gently brushing his dozing mother’s hair, in a role reversal of care giving. His chubby toddler arms end in hands which hold hair and brush confidently, his look one of concentration. Walton’s hair flows over and beyond his lap, individual strands highlighted as some also are on his head. Their curly freedom is repeated in the ties of his night shirt, visible over his left shoulder. The palette is low-toned, with highlights of colour in her lips, his hair and his clothing. The atmosphere is one of peaceful intimacy, somewhat at odds with the early morning shenanigans experienced by many parents of young children.

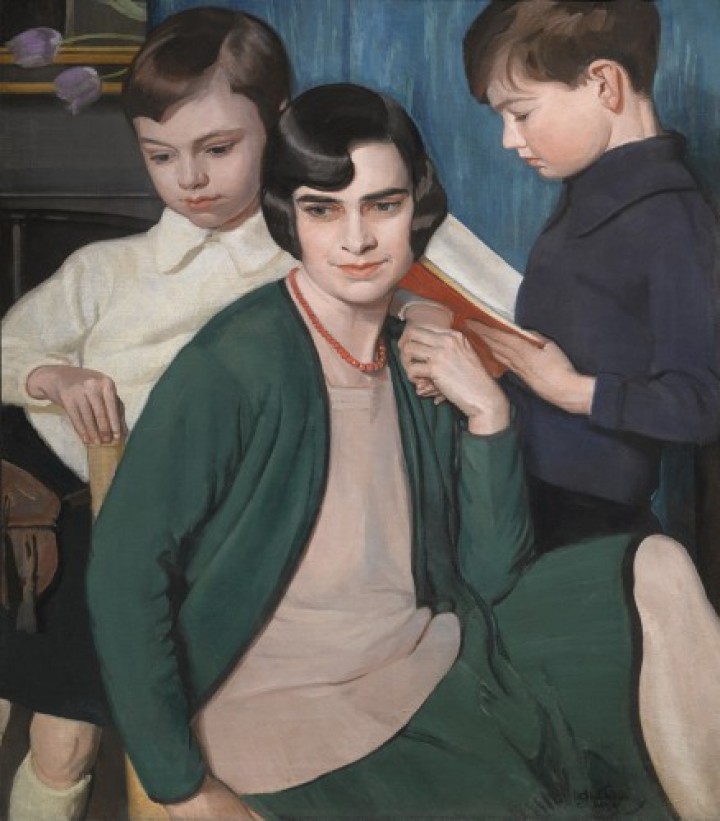

William Oliphant Hutchison (1889-1970), Reading Aloud, Margery and the Boys, 1929 © The Artist’s Estate

William Oliphant Hutchison (1889-1970), Reading Aloud, Margery and the Boys, 1929 © The Artist’s Estate

Reading Aloud, Margery and the Boys of 1929 by William Oliphant Hutchison (1889-1970) is a father’s depiction of his love for his wife and their children. He too trained at Edinburgh College of Art and later became Director of Glasgow School of Art. Hutchison married Cecile Walton’s younger sister Margery (1898-1977) in 1918 and their sons Henry and Robert were born in 1919 and 1922 respectively.

Whilst each of the sitters in the painting is absorbed in their own thoughts and activities, their physical contact and closeness nevertheless reveals loving relationships. Prominence is given to the mother, around whom the boys gather. The focal point of the work is the meeting point of hands at its upper centre. Swathes of deep green in Margery’s outfit are balanced by the blue of the background drapery, from which another trio, this time three tulips, peek out. The red of Margery’s necklace and that of the book cover beside it provide further pictorial structure. One can only imagine that a reunion of the sisters Cecile and Margery and of their sons, cousins to each other, would be joyful after the weeks of lockdown.

Anne Redpath (1895-1965), Window in Menton, 1948 © The Artist’s Estate / Bridgeman Images

Anne Redpath (1895-1965), Window in Menton, 1948 © The Artist’s Estate / Bridgeman Images

Window in Menton of 1948 by Anne Redpath (1895-1965) is at first sight an image of a happy holiday on France’s Côte d’Azur, but it is also a celebration of the artist’s rapport with her future daughter-in-law. Another alumnae of Edinburgh College of Art, Redpath married the architect James Beattie Michie (1891-1960) in 1920. They lived in France for fourteen years, where their three sons were born. The youngest was the artist David Michie (1928-2015) and he married the scientist Eileen Michie (a distant relative, 1927-2003) in 1951.

In this work, Eileen is seen from behind, sitting peacefully at a table before an open window, through which a view of Menton is visible. The eye is led from the still life arrangement beside Eileen, to the window-sill to the trees silhouetted on the top of the distant hill. The heat of the season is indicated by the cacti and palm trees, but also by the warmth of Redpath’s palette, for example in the patterned wallpaper and brightly-coloured buildings. Redpath originally painted the window-sill passage whilst staying with friends in Menton. She combined that with the view and Eileen after returning home to Edinburgh. The result is a portrait of a comfortable relationship between women of different generations, rather than a character description of an individual. May it provide solace at a time when many are concerned about elderly parents, who still have to self-isolate for some time to come.

Alice Strang is a Curator and Art Historian of Modern and Contemporary Art