Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

Like a Huge Scotland

By Neil Cooper, 09.11.2022

If travel broadens the mind, how to capture an unexpected moment that changed everything beyond mere postcards home? This is something Mark Cousins’ new four-screen film installation attempts to tune in to, as he channels a once-in-a-lifetime epiphany experienced by St Andrews born artist Wilhelmina Barns-Graham (1912- 2004). This occurred in May 1949, when Barns-Graham climbed the Grindelwald glacier in Switzerland. Whatever intoxicated her up there on what was meant to be a mere away day excursion left its mark on her mind’s eye with such force that she never quite came down.

This is evident from the cycle of paintings drawn from that afternoon, which at points beam out from each screen like transmissions from Barns-Graham’s brain. Cousins immerses the viewer inside the works alongside his own retelling of the event. This comes by way of a subtitled dialogue between the older and younger Barns-Graham indicated by photographs taken of her fifty years apart. The cross-generational discourse that results opens up a colour-soaked gateway into worlds beyond worlds.

While a thirty-something year old Barns-Graham’s peers into the camera with the steely fearlessness of a woman on track mere weeks after the event, half a century later, and now in her eighties, her face is etched with wisdom and experience. Together, these two secret selves bridge the decades as they recall the incident that helped shape everything that came afterwards, however much the memory might have faded.

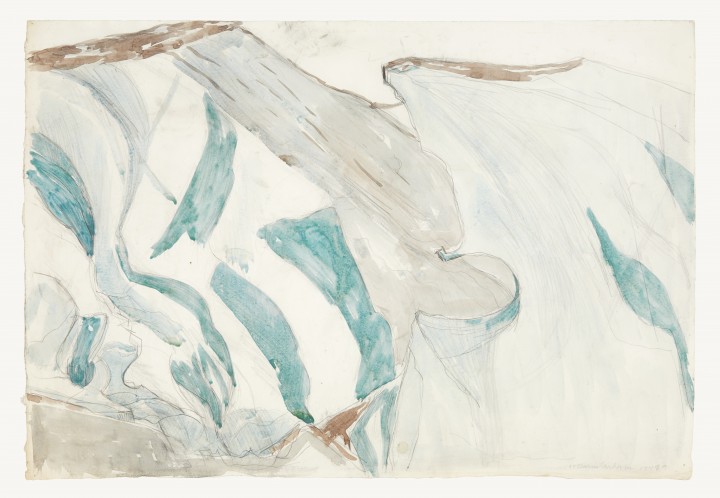

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham, Glacier, 1949. Gouache and pencil on paper. © Wilhelmina Barns-Graham Trust.

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham, Glacier, 1949. Gouache and pencil on paper. © Wilhelmina Barns-Graham Trust.

Barns-Graham’s conversation with herself is punctuated by the noises of Ania Pryzgoda’s sound design, as an exhausted but exhilarated voice gasps for breath while water drips within the melting glacier. This is accompanied by Linda Buckley’s slow-burning cello-based score, played by Kate Ellis with as many wide-open spaces as the images. This fusion of sound and vision over the film’s fifteen-minute duration reflects Barns-Graham’s own synaesthesia that made her ways of seeing so singular. Her moment of Zen satori in Grindelwald envisages the glacier singing what the words on the screen call ‘a song to the siren’.

Beyond its attempts to pin down a moment of enlightenment, a sense of loss pervades Like a Huge Scotland. This comes not only in the decimation of the glacier between the time Barns-Graham first climbed it to when Cousins followed in her footsteps. It highlights too the effects of human ageing, and the realisation of one’s own mortality, when life changing totems of the past are all you’ve got.

Some of Barns-Graham’s studies of the glacier painted in the wake of her climb line the corridor beside the Fruitmarket’s low-lit Warehouse space, where Cousins’ work is housed. The sense of wonder that inspired them remains palpable even in the silence. Meanwhile, back on the screen, Cousins puts a full stop on things with a quote from Gertrude Stein about how the doors of perception are opened. This is followed by a view that goes beyond words, moving mountains in its wake.

Like a Huge Scotland runs at Fruitmarket, Edinburgh until 27th November