Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

John Patrick Byrne - A Big Adventure

By Greg Thomas, 20.06.2022

This new exhibition of painting, drawing, and sculpture by John Patrick Byrne (b.1940) displays in prominent position a 1968 quote from GW Lennox Paterson, Deputy Director of Glasgow School Art: ‘Byrne is unquestionably one of the most able painters we have seen in the past 20 years. He is something of a ‘chameleon.’ We have had paintings by him ranging from Bonnard to Picasso, which the masters themselves could not have failed to admire.’

The chameleon tag perhaps predicts a critical opinion that would grow up around Byrne’s work, and which curator Martin Craig wants to acknowledge and move past early on: that there may be an absence of depth behind Byrne’s impish and prodigious play of visual styles.

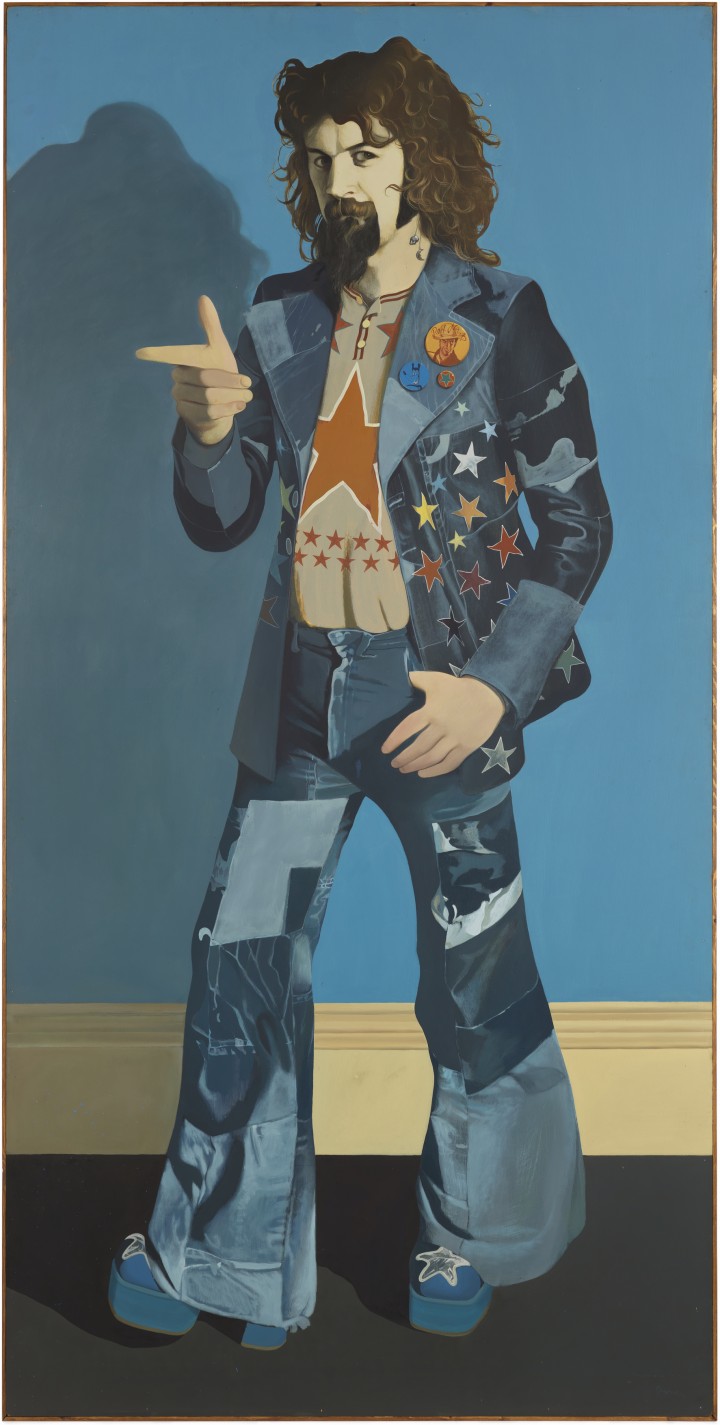

John Byrne, Portrait of Billy Connolly (b.1942). CSG CIC Glasgow Museums Collections © John Byrne. All rights reserved. DACS 2022.

John Byrne, Portrait of Billy Connolly (b.1942). CSG CIC Glasgow Museums Collections © John Byrne. All rights reserved. DACS 2022.

An early vitrine of works produced at Glasgow School of Art during 1958‐63 confirms the technical ability: nudes and seated groups are endowed with a living sinuousness that many artists who remain in a sombre, naturalistic style would envy. But from there on in the show flits enjoyably between reference points. Early works signed off in Byrne’s ‘outsider artist’ moniker ‘Patrick’ have something of the huge fleshiness of Stanley Spencer, while strange interior scenes such as Jock and the Tiger Cat (1968) riff on surrealist iconography.

There are animal studies set in dark dreamlike forests, like Owl (ca. 1968), which bring to mind Henri Rousseau, while in various self‐portraits and landscapes the Fauves and Impressionists are emulated with equal glee and dexterity—so too, here and there, is the dapper fin‐de‐siecle atmospherics of Whistler. Billy Connolly and Banjo (1974), indicative of Byrne’s artist‐to‐the‐stars status, sits comfortably in the pop‐realist Zeitgeist of the Hockney era, but sketches of family members show a tender naturalism (see Celie [2010]).

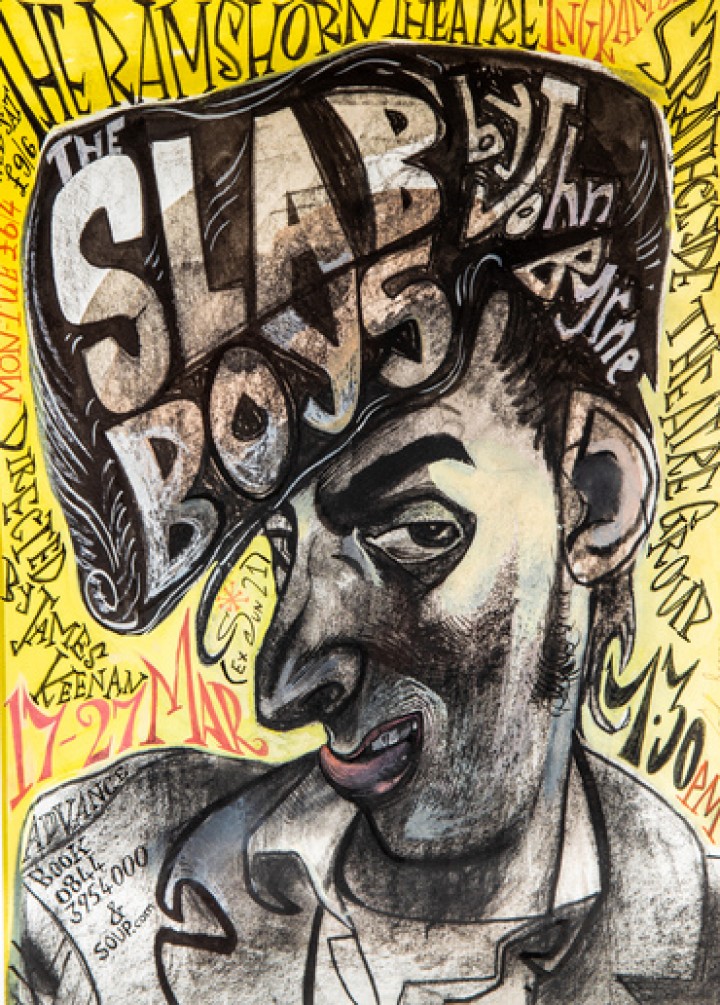

Slab Boys poster. Private Collection, Charles Marks. © John Byrne. All rights reserved. DACS 2022.

Slab Boys poster. Private Collection, Charles Marks. © John Byrne. All rights reserved. DACS 2022.

Byrne’s status as an accomplished writer for stage and TV writer makes sense here. Ultimately, he is a masterful inhabitant of character. The point applies both to his depiction of subject‐matter and his intuitive‐seeming grasp of myriad compositional styles.

Indeed, it’s perhaps in his thematic choices that a kind of unity emerges. With his commissions for album covers, painted banjos and guitars, his portraits of comedians and film‐stars, Byrne is an acolyte of pop culture and especially pop music, who came of age in the post‐modernist paradigm of the 1960s‐70s, when this was a new and laudatory subject‐matter for fine art—and when a chameleon‐like feint across formal approaches was perhaps the whole point. Certainly, the viewer won’t leave bereft of a sense of warmth, humour, or playful adventure.

Visit at Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, until 18th September.