Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

John Andrew (1933-2021)

By Greg Thomas, 11.11.2021

In interview, John Andrew spoke lucidly about his working-class roots, which seemed to give him an acute perspective on the inside circles and foibles of the British arts scene untainted by bitterness. Born in Bethnal Green, East London, he traced his paternal name back to Scotland, which he speculated his ancestors had left during the clearances. His family moved to Elm Park, Essex in 1936 when John was still a toddler, part of the first wave of working-class migration to new suburban and planned communities across south-east England. Wartime evacuations followed, first to Manchester and then to Twickenham, where a technical secondary education followed. John’s formative memories including endless modelling with plasticine and carving a highly acclaimed wolf’s head for his local Cub-Scout pack.

Leaving school at 16, the aspiring carver secured an apprenticeship at Kingston Masonry Company (his mother applied on his behalf on the strength of his wolf-head carving!) whose owner Fred Relph counted Eric Gill amongst his clients. The position allowed one day per week for “educational release,” which was spent at the sculpture department of Kingston School of Art; soon John could be found there each weeknight as well, studying towards a National Diploma in Design ('my home life was pretty well non-existent,' he recalled). A period of military service followed, with the Royal Engineers in Germany during 1956-58, before a return to to education.

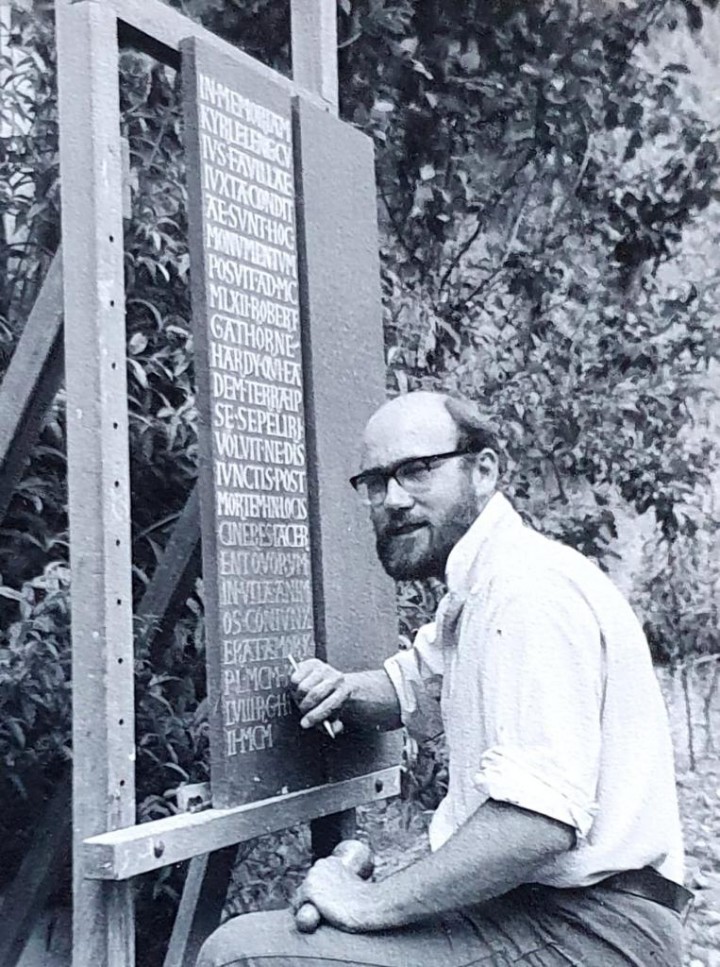

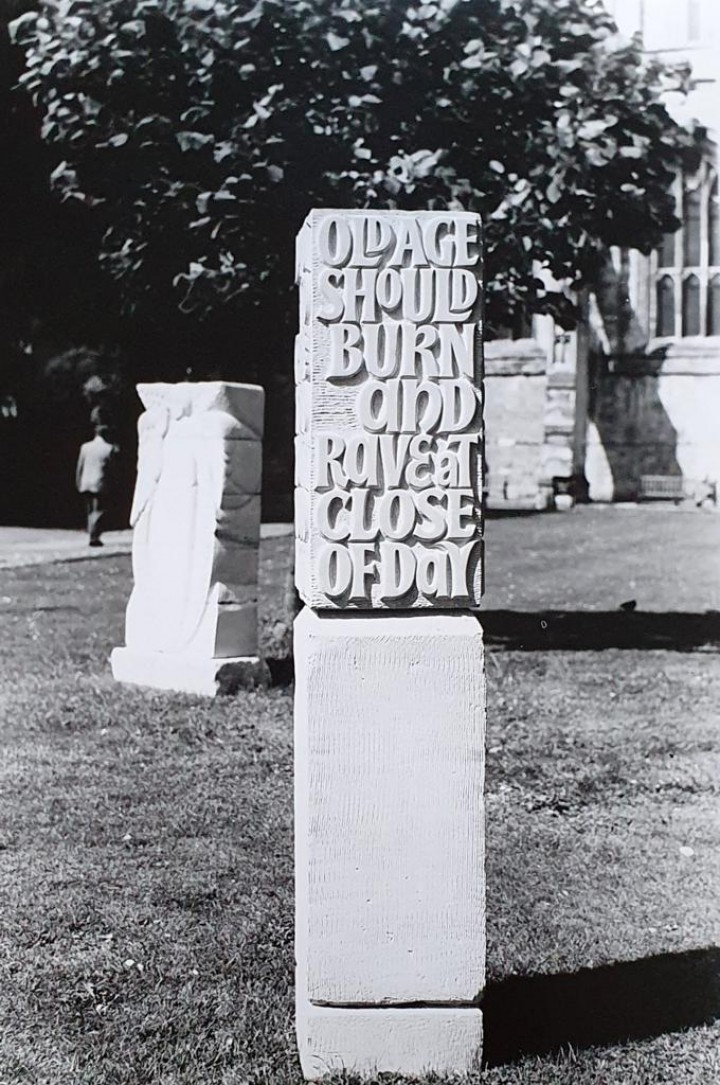

Carving of a poem by Dylan Thomas.

Carving of a poem by Dylan Thomas.

Encouraged by tutors at Kingston, John obtained a highly sought-after spot on the sculpture course at the Royal College of Art – contemporaries included David Hockney, Pauline Boty, R.B. Kitaj, and the director Ridley Scott – where he stood out for his stone carving amidst a cohort of clay modellers. This predilection, and John’s evident talent, caught the eye of the artist John Skeaping, head of the sculpture department, who took his student on to work with him over his first summer vacation on a large mural for Imperial College, described by John as 'a 40-foot row of black Irish marble covered in panels of algebra, like E=MC2,' a project which strengthened his interest in letter-carving. Eventually, the young artist’s lack of interest in clay modelling – then a ubiquitous medium at the RCA – brought pressure on him to adapt or shift course. Choosing the latter route, he eventually graduated with a degree in graphic design, which he had already developed a passion for through his lettering work with Skeaping. This varied training equipped John with a versatility later valued by the Scottish artist and poet Ian Hamilton Finlay, who would commission him both for stonework and graphics projects.

Leaving RCA in 1961, the new graduate was taken on as an assistant by Reynolds Stone, the most celebrated woodcutter and typographer of the post-Gill generation, who taught letter-cutting one day a week at the RCA, and whose outgoing assistant Michael Harvey would precede John in working with Finlay. Stone and his wife, the portrait photographer Janet Stone, were, according to John, 'great socialities,' whose weekend parties at their house and studio in Litton Cheney in rural Dorset attracted luminaries of the upper-class artistic and literary scenes of mid-twentieth-century Britain: 'I met Benjamin Britten, John Betjeman, Cecil Lewis, Irish Murdoch, Compton Mackenzie…This East End kid meeting the whole establishment of English society: it was always interesting.' John also noted that the circumstances of his rural idyll meant that 'the swinging sixties pretty much passed me by.'

Part of Ian Hamilton Finlay's A Wartime garden, carved by John Andrew.

Part of Ian Hamilton Finlay's A Wartime garden, carved by John Andrew.

Jobs with Stone included a large amount of intricate heraldry and headstone-carving for wealthy, often landed clients. The Bonham-Carter and Asquith families were important patrons, and much carving and lettering was undertaken by the pair at St. Andrew’s Church in Mells, Somerset, famous for its illustrious roster of contributing artists and craftspeople, from Eric Gill and Edwin Lutyens to Edward Burne-Jones and Alfred Munnings. John had vivid memories of re-inscribing a tombstone for the theologian Ronald Knox. This was the kind of meticulous, old-fashioned direct carving that Finlay was looking for by the late 1960s, when he began to turn the grounds of his derelict Farmhouse at Stonypath in the Pentland Hills into a transportive landscape of poem-sculptures, Little Sparta.

It was at the start of the following decade that Finlay asked Michael Harvey to recommend a stone carver whose repertoire extended beyond the lettering work in which Harvey excelled so brilliantly. Andrew recalled in interview that 'Michael knew me from the heraldic work I was doing for Reynolds, and was able to recommend me to Ian.' Finlay and Andrew initially began working together remotely – as was the way with many of the agoraphobic Scot’s creative relationships – on a wide range of projects for the rapidly developing garden. Equally typically, John’s creative aptitude was immediately tested to its limits: 'one of the first things I did was a flail tank, with this arrangement of chains on a roller in front.…To carve one of those in action was, in a word, fiddly. I'd probably carved more complicated bits of heraldry, but that that was quite a taxing task, and one of the earliest ones I did.'

.jpg) Late 1970s carving.

Late 1970s carving.

John struggled to recall which job for Ian came first—there were simply so many. But his description of a typical visit to Little Sparta was splendidly evocative: 'Quite often I would go up there to add lettering to carving someone else had done...and I stood up in little streams and carved keystones over arches and bridges, and Ian would supply waders....He used to put me up in a little bedroom for visiting artisans above what he came to call the Garden Temple….It was pretty freezing. I think we had some little paraffin stove or something. So, you know, it was a Spartan existence!'

In a list compiled for Jessie Sheeler’s 2015 guide book Little Sparta, Sheeler and Patrick Eyres calculated that John executed 32 works across the garden, not counting other iconic collaborations such as the Et In Arcadia Ego stone tablet, the Wartime Garden relief sculpture series now owned by the Tate, and various graphic works such as the poster Lullaby. Notable sections of the Little Spartan landscape shaped by John’s hand include the Roman Garden – an early collaborative venture featuring his stone models of toy military vehicles – and the sleek slate Nuclear Sail, an equivocal monument to the military sublime on the near shore of Lochan Eck. (This was, incidentally, the source of their only serious falling out, over a disagreement concerning payment.)

A child's memorial carved 1993.

A child's memorial carved 1993.

John spoke of his work with Finlay – whose instructions were, admittedly, always exacting – with a down-to-earth humility belying the significance of his role: 'I saw a comparison between my chisels and Ian with collaborators. There’s a thing called a pitcher and there’s a punch, there’s a claw, then there’s a fine riffle or a polishing rub stone, and so on, all of them useful for particular tasks. And really, that’s exactly how he worked with the collaborators. He was selecting people who could execute particular ideas.' The art historian Stephen Bann offers a less effacing analogy for John’s handiwork in comparing many of Finlay’s skilled collaborators to the figure of the orchestra conductor: not just a brilliant technician but also someone who 'takes the risk of performance…conducting the project in a virtuoso style which draws a large measure of attention to his own deliberate extension of the possibilities latent in the score.'

Another significant strand of John’s creative biography involved the group Memorials by Artists – now the Lettering Arts Trust – set up in 1985 by Harriet Frazer. Frazer was looking for a suitable monument to her stepdaughter, Sophie Behrens, who had died tragically young, and was surprised by the difficulty of finding skilled artisans to undertake work of this kind: particularly given that, as John put it, 'if ordinary people, in inverted commas, are going to commission any stone work, it’s going to be a headstone or a memorial of some sort—it’s rarely going to be artworks or garden ornaments.' Frazer reached out to John while assembling a pool of skilled carvers, letterers, and sculptors – many of whom worked with Finlay – and was amazed at the outset to discover that John had already produced a memorial to another relative of hers, the writer Robert Gathorne-Hardy. John went on to work for decades for MBA, whom he credited with reviving many traditional carving techniques through an innovative apprenticeship scheme.

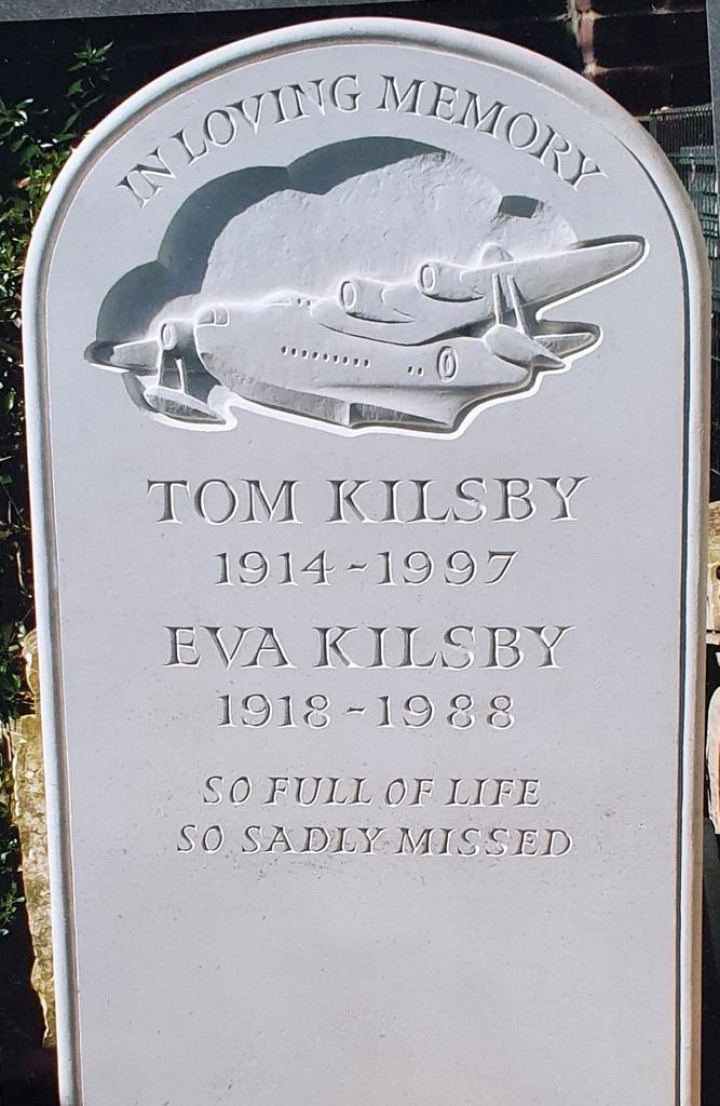

Memorial to John's uncle, Tom Kilsby, 1999.

Memorial to John's uncle, Tom Kilsby, 1999.

John’s humility regarding his own work might seem to have obscured his exceptional talent, but it reflected a deep historical perspective on his craft, which he summed up in interview by placing himself in the company of medieval guildsmen: 'the early twentieth century saw the revival of direct carving, brought back to public esteem by artists like Jacob Epstein, Eric Gill, Henry Moore, and Barbara Hepworth….They revived a strong English tradition dating back at least to the Middle Ages and the mason carvers working on various subjects, to the glory of God and not egotism. And that’s where I’m at—I’d put myself with the medieval carvers I’d say.'

John Andrew is survived by his wife Pauline, his son Matt (an accomplished letter cutter taught by his father), and grandsons Sam and Noah. His daughter Vicky, a skilled graphic designer, predeceased him.