Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

James McBey’s Revival

By Susan Mansfield, 09.01.2023

James McBey has not gone down in history as a celebrity artist. If the Aberdeen-born painter and printmaker is remembered at all, it is for his excellence as an etcher. Today, his works, while accomplished, seem to belong to a different era.

Few are aware that, in the 1920s, McBey was the toast of the art world, and his highly prized etchings were compared to Rembrandt and Whistler. From humble beginnings in rural Aberdeenshire, he rose to fame in Edwardian London and travelled to the Middle East during World War I as an official war artist. His long and colourful life, full of adventurous travels and tempestuous affairs, still makes compelling reading.

“His life is cinematic,” says journalist Alasdair Soussi, whose biography, Shadows and Light: The Extraordinary Life of James McBey, has just been published. “He was born illegitimate in the Victorian era in the North East of Scotland and died 75 years later in Tangier, Morocco. He painted Lawrence of Arabia and was feted on both sides of the Atlantic. I was just blown away by his story.”

Recently, there have been indications that interest in McBey’s work could be rekindled. The Fine Art Society staged an exhibition, The Wonderful World of James McBey, in Edinburgh in December 2022 and will take some of his work to New York in 2023. Aberdeen Art Gallery, which holds much of McBey’s archive, will mount a show in February 2023 co-curated by Soussi.

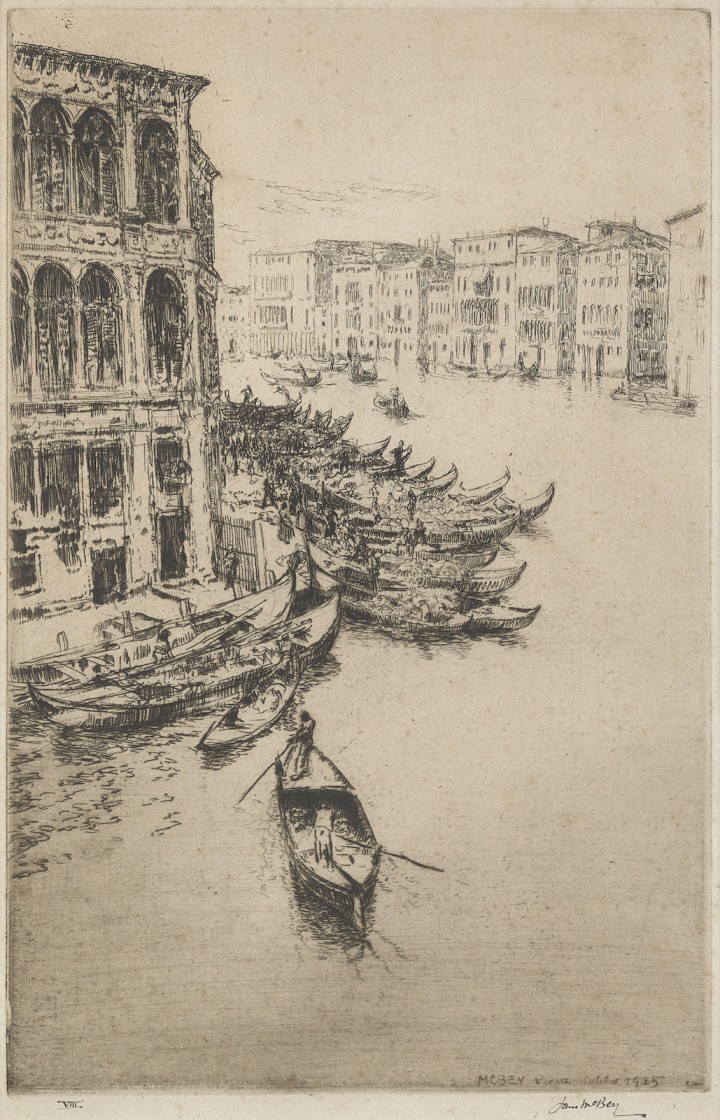

James McBey, Palazzo dei Camerlenghi, 1926.

James McBey, Palazzo dei Camerlenghi, 1926.

McBey was born in 1883 in the hamlet of Foveran, north of Aberdeen, the illegitimate son of a blacksmith’s daughter. Leaving school at 15, he secured a job as a bank clerk in Aberdeen, but ever since winning a local drawing competition as a child, his heart was set on a career in art. His early years were far from easy. His mother was a distant figure, with failing eyesight and fragile mental health. When he was 22, his mother took her own life in the basement of their Aberdeen home. McBey found her body.

He worked at the bank for 11 years, taking evening classes at Gray’s School of Art, and quickly gravitated to etching, teaching himself techniques from books he found in the city’s Central Library. His first prints were made using the household mangle, before he persuaded his blacksmith uncle to build him a simple press, but even his earliest works show tremendous aptitude. In 1906 a print was shown at the RSA.

McBey left Aberdeen for London in 1911. When the prestigious Goupil Gallery hosted his first solo exhibition, he recorded in his diary that he was disappointed at the turnout at the private view, but his attitude changed when 29 prints sold within two days, rising swiftly to more than 70. Soussi says: “He was the big rock’n’roll artist. He was the full package, he was young, handsome, charismatic, talented, he was the bright new shining thing in pre-war Britain.”

In 1917, he secured a commission as official war artist with the British Expeditionary Force in the Middle East. Soussi says: “He was hot-footing it all over the place. He was in Jerusalem when it was taken by the Allies in December 1917, he witnessed the fall of Gaza and Damascus. He painted all the main protagonists on the Palestinian Front: Field Marshall Allenby, T E Lawrence, Emir Faisal [whom he later described as “the worst sitter I ever had”]. In between all that he had a passionate affair with a married British woman in Egypt, and still managed to make this wonderful art.”

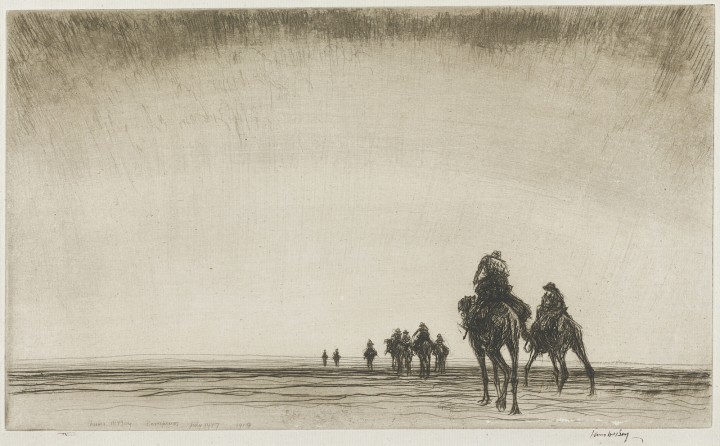

McBey came back from the war with his reputation enhanced, and with an enduring fascination with the Arab world. Prices for etchings were sky-rocketing on both sides of the Atlantic, and McBey was one of the “big three” printmakers, along with fellow Scots David Young Cameron and Muirhead Bone. In 1926, McBey broke the record for the sale of a print by a living artist for his wartime image ‘Dawn, Camel patrol setting out’.

He travelled to Venice, producing what some regard as his finest work. In 1928, a partner at art dealer Colnaghi’s turned up at his studio and bought trial plates for the first eight of his Venice works for the unprecedented sum of £5,250. Lowell Thomas, the American journalist largely responsible for the myth of Lawrence of Arabia called him “the best etcher since Whistler”, while the critic for the Boston Globe compared him to Goya.

However, the Wall Street Crash of 1929 had a devastating impact on the print market, bad timing for McBey who had just arrived in New York. “But he was a great adaptor,” Soussi says. “He kept etching, but moved towards painting in oils and watercolours. He was pretty good, not a genius the way he was with printmaking, but he still produced wonderful works.”

In 1930, at a dinner in Philadelphia, he met Marguerite Loeb, beautiful, accomplished and 20 years his junior. They married in New York the following year. Both intrepid travellers, they set sail from London for Spain, then Morocco, which McBey had visited in 1912, and bought a house in Tangiers.

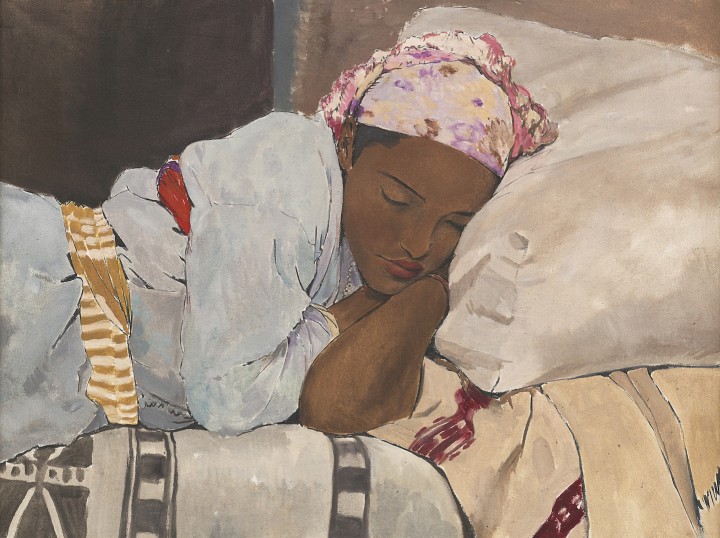

James McBey, Zohra, Moroccan girl sleeping, c. 1950.

James McBey, Zohra, Moroccan girl sleeping, c. 1950.

Apart from the difficult years of the Second World War when the couple were forced to return to America, and McBey painted boardroom portraits to make ends meet, Morocco would be their home until his death in 1959. While he still travelled a great deal, including making visits back to Scotland, the majority of his work was done in Morocco, in Tangier and Marrakesh, including an outstanding portrait of Zohra, the couple’s maidservant, which is described as “the Moroccan Mona Lisa”.

His decision to settle far from the centres of the art world is one reason why McBey’s reputation faded in the second half of the 20th century. Also, he was little inclined to play what Soussi calls “the establishment game”, courting the right galleries or membership of the right societies. When he heard that his name was being put forward for membership of the Royal Academy, he asked for it to be withdrawn.

Soussi says: “One of the things I admire most about him is that he was his own man. When a lot of his contemporaries were being knighted, he didn’t care for that, he ploughed his own furrow in life. It made him selfish too. I think he was a difficult man to live with, which many of the women in his life might have attested.

“One of my biggest hopes is that the book helps propel him into the public consciousness and gives him his rightful place in history as an international Scot. A lot of Scots punched above their weight in terms of their achievements, and he definitely fits that mould.”

'Shadows and Light: The Extraordinary Life of James McBey', by Alasdair Soussi, is out now, published by Scotland Street Press. 'The Wonderful World of James McBey', at The Fine Art Society, can still be viewed online. An exhibition of McBey’s work and archive material, Shadows and Light, will be at Aberdeen Art Gallery, 11 February to 28 May.