Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

Isolation in Scottish Art: Richard Walker

By Susan Mansfield, 15.06.2020

In the closing decade of the 18th century, Xavier de Maistre, a young French aristocrat, was confined to his room in Turin for 42 days after taking part in a duel (one assumes he was victorious and, duelling being illegal, had to lie low). He passed the time, in part, by writing a book called 'A Journey Around My Room', an investigation into how far one can travel, imaginatively and philosophically, while confined by four walls.

As we live in Covid-19 lockdown, most of us becoming increasingly familiar with our own walls, de Maistre’s book takes on a new resonance. As does the work of Scottish artist Richard Walker, whose paintings of dimly lit interiors - often of his own studio - show us just how much an artist can do in (albeit self-imposed) confinement.

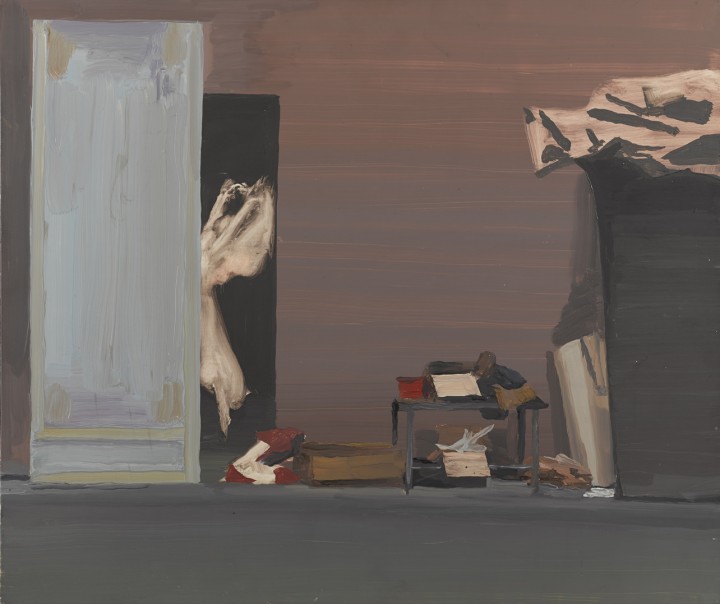

Walker studied at Glasgow School of Art in the 1970s, when the figurative painting wave was building (it would crest a few years later with the New Glasgow Boys). But he took a different path, “slowly removing the figures” from his paintings, “focusing on what were essentially backgrounds”. Working as a scene painter at Scottish Opera, he learned the power of the background. He also painted pictures in the empty workshops where the charge of past performances seemed to linger among the curtains, props and fake walls.

Richard Walker. Cloths and Door, 2002. Ⓒ The Artist.

Richard Walker. Cloths and Door, 2002. Ⓒ The Artist.

In this way, Walker sits within the tradition of artists who painted behind the scenes at theatres, or painted their own studios, or painted the world as if it was a stage set. His paintings of the 1990s and early 2000s have something of Edward Hopper about them: windows open to the night sky, rooms the inhabitants have just vacated, objects - a rubbish bin, a pile of crumpled dust sheets - evoking human absence.

His concerns are the concerns of centuries of painters: the alchemy of capturing light, the illusion which can be created on the painted surface. He complicates the task further by working in near darkness, then manipulating light using spotlights, mirrors and projectors. He takes photographs on his mobile phone and projects them onto white sheets, and the workings - the projector, the laptop, the sheets balanced on poles - are laid bare within the paintings. Yet we are made to question what we see. As well we might, for the eye is no camera. We see from different angles, apply our own filters, see what we want to see, what we saw last week or last year. All this he explores.

In 2011, Walker made a series of paintings at The Haining, a country house near Selkirk. In its shabbily grand interior, he let sunlight seep round the edges of the closed shutters, and used projection to bring echoes of one room into another. The results are atmospheric, unsettling. In the half-lit stillness, it is difficult to distinguish the reality from the reflection, the living world from its ghostly echo.

Richard Walker. Wall and Scenery, 2002. Ⓒ The Artist.

Richard Walker. Wall and Scenery, 2002. Ⓒ The Artist.

More recent work has brought the focus back to the studio, fragmenting the field of vision with increasing ambition, even sawing up and collaging the sheets of plywood he paints on. There are shades of cubism, surrealism, abstraction in some of these works, but the root of them all is still observation, the difficult business of seeing what is really there, which one critic described as his “systematic encounter with reality”.

It is also a systematic encounter with painting itself. By imposing limits - low lighting, a dark palette, the limits of a single physical space - he explores what paint is capable of. He makes a case for contemporary painting, which is in danger of being trapped in ironic, self-conscious dialogue what has gone before. Walker works within painting’s traditions but is not bound by them. He is energised by paint, its potential, its materiality, and by the questions it asks us about how we see the world.