Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

Isolation in Scottish Art: Charles Avery

By Susan Mansfield, 13.05.2020

In 2004, Charles Avery made what felt like a bold decision: to spend the rest of his life working on a single artistic project. That project is the description of an island, its people and topography, flora and fauna, culture and belief systems.

With each drawing, sculpture, text and installation, our sense of the Island grows fuller, richer. When Avery explores new aspects of it, they come into focus. It is as if, in the words of the curator and critic Nicolas Bourriaud, he is discovering it and inventing it at the same time.

Speaking about his decision in March, on the BBC Radio 4 programme 'Only Artists', Avery said: “I just needed somewhere to isolate myself… protect myself from the forces of the art world at large, take that territory of art back for thinking and exploring, rather than just making pieces.”

The Island, then, can be understood as a form of self-isolation. Avery dropped out of art school after six months; he is self-taught. In 2004, the art world was beginning to take an interest in his work. In response, he wanted to create a physical territory in which he could explore his ideas freely, maintain the integrity of his vision. It’s no coincidence that his chosen territory is an island: islands are self-contained, hard to breach.

Avery has said of the Island: “It’s not a fantasy land, it’s just another place.” He talks about it as if its autonomous existence is unquestionable: the city of Onomatopoiea is transforming out of post-industrial gloom in a Bilbao-style renaissance; tourists in the markets are being fleeced by the sellers of eggs pickled in gin (disgusting, but dangerously addictive). Ask him about the Island’s stone mice and he is liable to take one from his pocket to show you (though, once removed from the Island, they are simply stones).

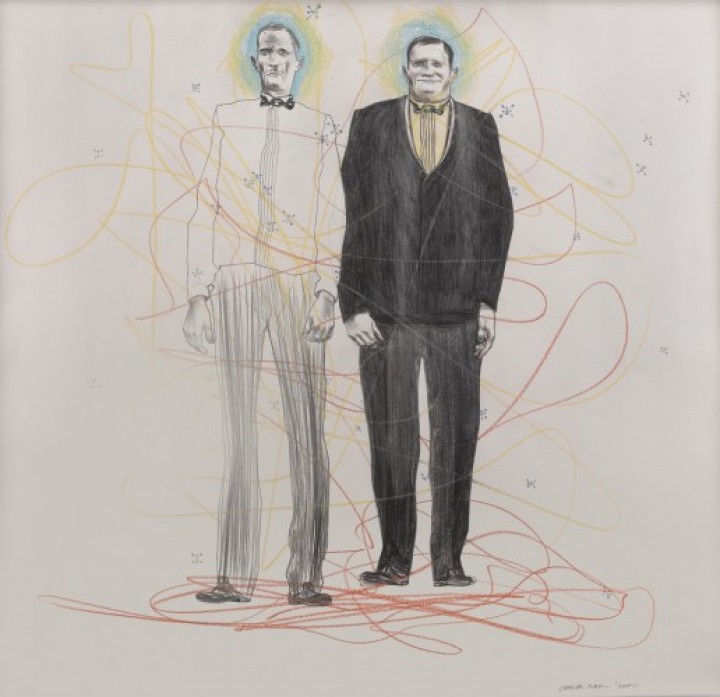

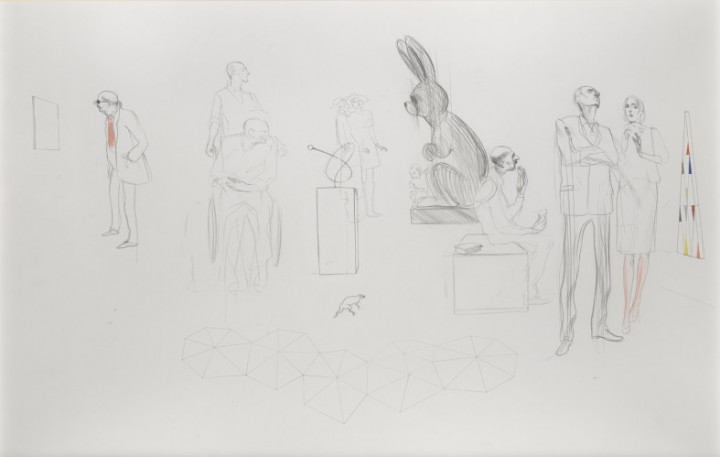

Charles Avery, Gallery, 2000. The Fleming Collection. Ⓒ Charles Avery. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2019.

Charles Avery, Gallery, 2000. The Fleming Collection. Ⓒ Charles Avery. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2019.

In Avery’s 2008 book 'The Islanders: An Introduction', hapless explorer Only McFew lands on the shore and encounters the enigmatic Miss Miss. “This isn’t real,” he says, trying to find a way to understand his new surroundings. “Everything is real,” she replies. As we encounter the Island, we are wont to make the same mistake. The Islanders don’t distinguish between the physical and the imaginary. Words such as “real” and “unreal”, “fiction” and “fantasy” are unhelpful.

It’s a place where ideas take on physical form. A Ridable (canine head, llama body, chicken’s feet), or a perfect pyramidal mountain, begin life in drawings, then take on three dimensions in sculpture. Philosophical and mathematical concepts take form too: Descartes’ Axiom appears on maps; Kant’s Noumenon is a yeti-like creature pursued by bounty hunters. There is a character called Mr Impossible (and he is a proper pain in the ass). Avery has also described the island as a “gymnasium”, an exercise yard for thinking. He hopes it can be such for others as well as himself.

In 2015, ahead of his exhibition for Edinburgh Art Festival, Avery talked about the project with a new sense of anxiety. He had made it his lifework, with the intention that by the end of his life it would be complete. Now, he seemed to be measuring the limitless potential of the Island against the finite span of a human life. It’s a sobering lesson for all who create parameters for the imagination. That, in itself, is a creative act. An island can turn out to be infinite after all.