Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

Isolation in Scottish Art: Carol Rhodes

By Susan Mansfield, 07.07.2020

Had the festival not been cancelled, this year’s Glasgow International would have featured a retrospective of work by the Glasgow-based artist Carol Rhodes, who died in 2018. The festival’s theme was Attention, which is interesting in regards to Rhodes, whose quietly distinctive paintings do the opposite of grabbing our attention. As the late Tom Lubbock wrote: “They wait for your close attention. When they get it, they unfold into an experience that’s large in resonance and complexity.”

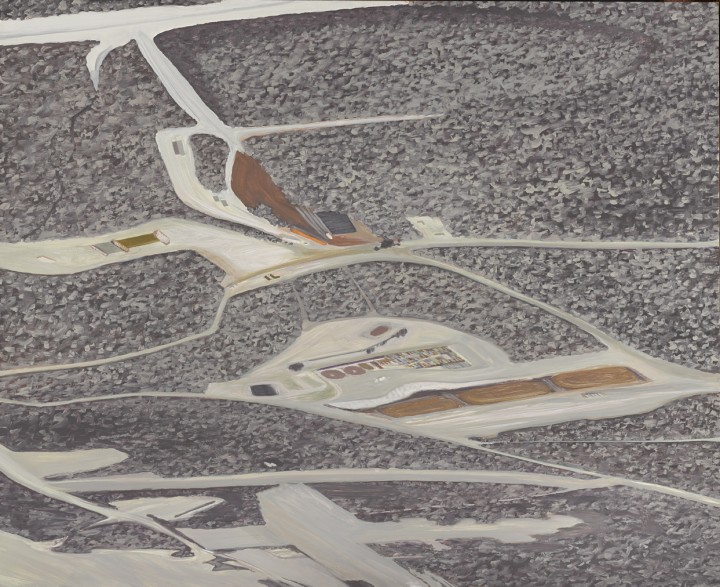

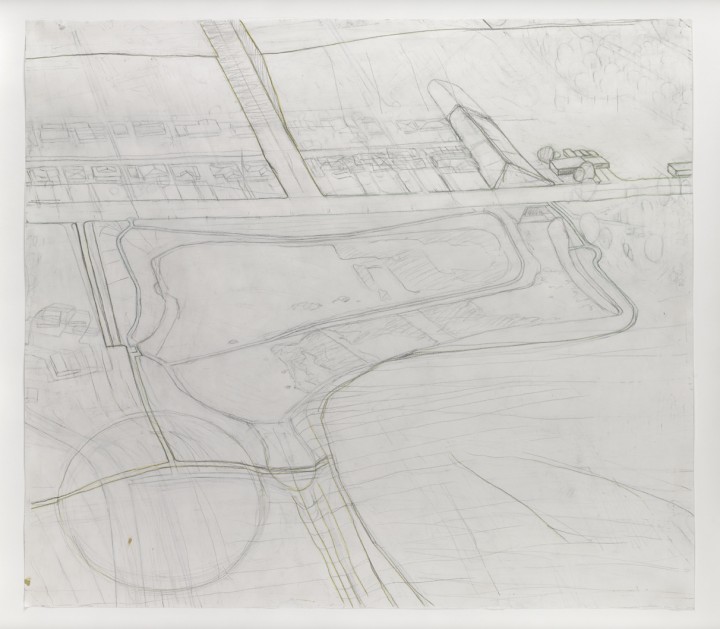

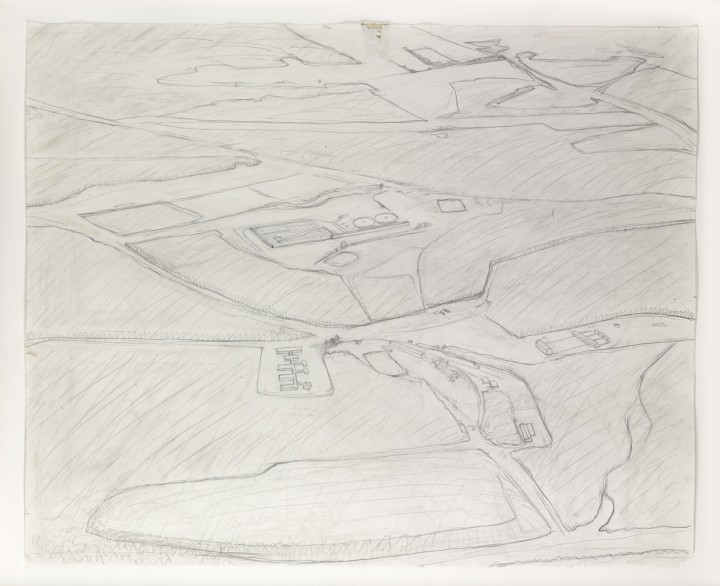

Rhodes’ paintings are landscapes. They are fictional compositions, sometimes drawing on books and photographs, often depicting the edgelands of modern life - motorway flyovers, industrial estates, car parks, airports, factories. They are seen from a distance, often from the air, like the non-places glimpsed from the windows of a descending plane.

They are also unpeopled. Writing on Rhodes’ work, New York Times art critic Ken Johnson described “a mood of numbed lonesomeness”. There are no vehicles crawling, ant-like along these motorways. The car parks are car-free. This is a landscape shaped by the hands of human beings, but from which people have retreated. Viewed from the perspective of the present moment, she might have been painting the lockdown world.

Carol Rhodes, Pond Area, 2008. © The Estate of Carol Rhodes

Carol Rhodes, Pond Area, 2008. © The Estate of Carol Rhodes

Rhodes’ paintings seem to grow increasingly resonant with time. She was painting from an aerial perspective long before Googlemaps became part of our lives, or drone footage became ubiquitous. She paints the overlooked but essential mechanisms of the post-industrial world, the reservoirs, sub-stations, warehouses and transport hubs which keep modernity in motion. And she captures what those places often make us feel: disorientated, isolated, part of a vast machine we don’t quite understand.

However, while writing of the Prozac-inducing emptiness of the pictures, Ken Johnson also describes how “the caressing feathery touch of the artist’s brush” gives the landscape “a feeling of soulful tenderness”. Reading about Rhodes’ practice, the word which comes up time and again is “meticulous”: the drawing, composing, the preparation of the panels, the painting, sanding back, repainting. These works testify to an intense engagement of hand and mind. A vision which at first seems dehumanised is re-humanised by the act of painting.

Carol Rhodes, Trees and Works, 2001. © The Estate of Carol Rhodes

Carol Rhodes, Trees and Works, 2001. © The Estate of Carol Rhodes

In ‘Earth/Body/Painting’, an insightful essay written in 2007, Rhodes’ partner, the artist Merlin James, cautions against the view that these works are simply ‘about’ landscape. They are intense conversations about the process of painting when painting is itself isolated in an ocean of conceptual practice. He also refers to the “wide-ranging associative meanings” in the works, one of which is a depiction of the body. “Organs, muscles, veins, skin and bones are continually suggested. The beautiful, strange, even fascinatingly repugnant forms and colours and textures in the work evoke those of our own bodies.”

Thus a landscape which might appear devoid of humanity is also full of references to the viscerally human; a perspective which appears to be distant or disorientating is also a close-up, literally, gets under the skin. While meditating on the large-scale mechanisms of which we are a tiny part, the works also suggest the tiny parts of the mechanisms inside us. And each aspect of this transformation is attended to with the artist’s characteristically meticulous care.