Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

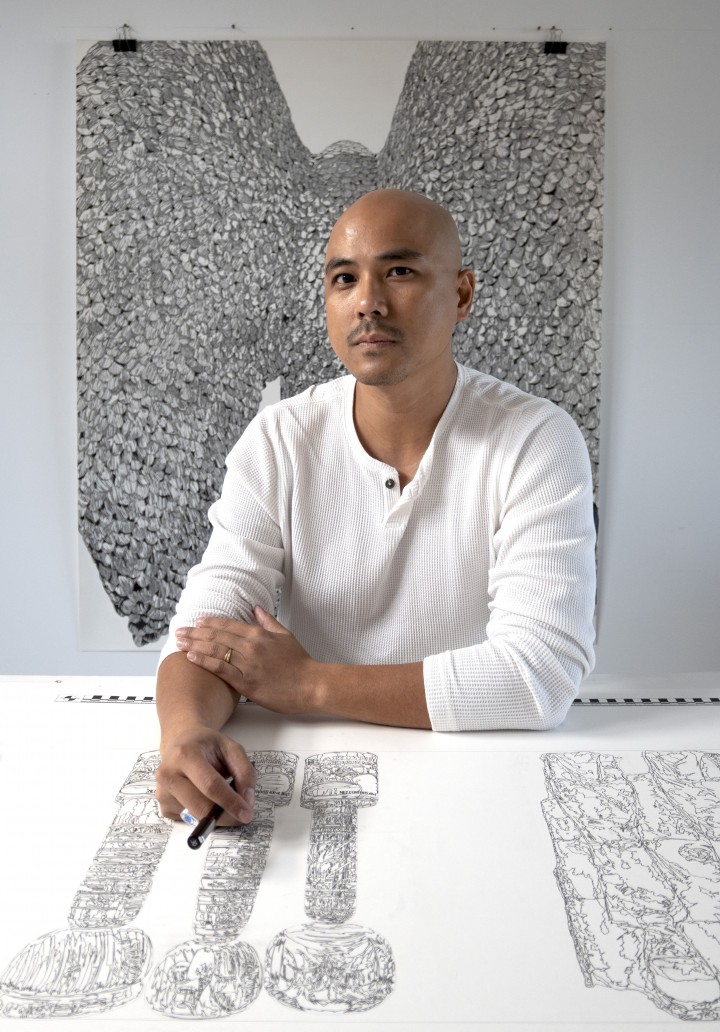

Interview: Pio Abad

By Susan Mansfield, 23.12.2024

If you’re looking for an audience for your work - and what artist isn’t? - there can be no better platform than being shortlisted for the Turner Prize. “It’s a case of being careful what you wish for because you might get it!” says Pio Abad, with a smile. The Manila-born, Glasgow-trained artist is on the 2024 shortlist alongside Delaine Le Bas, Claudette Johnson and fellow Glasgow School of Art graduate Jasleen Kaur, who was named as the winner on 3rd December.

“It’s been incredible,” he says. “I’m always blown away when I go back and see people visiting the exhibition. My work is quite demanding because you have to slow down and read and take in the details, and it’s really heartening to see people do just that.”

Abad was nominated for an exhibition he created for the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, after being given free rein to explore the Ashmolean and Pitt-Rivers collections. Starting by researching the connections to his own Filipino history, he then broadened the work into a larger conversation about colonialism, appropriation and how objects are witnesses to political events.

.jpg) Installation view of Pio Abad, Ashmolean NOW: Pio Abad, 2024. Courtesy the artist. Hannah Pye/Ashmolean, University of Oxford

Installation view of Pio Abad, Ashmolean NOW: Pio Abad, 2024. Courtesy the artist. Hannah Pye/Ashmolean, University of Oxford

“Everything emanates from Filipino history because that’s not just the history I know but the history I am,” he says. “My parents met as activists protesting the corruption and brutality of the Marcos dictatorship. Before I was born (in 1983) they had spent some time on the run, they had been imprisoned, and my eldest sister was incarcerated with them when they were held under campus arrest. On a deeply personal family level, Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos shaped so much of my life.”

In the introductory film accompanying his Turner Prize show, Abad describes Imelda Marcos as “my muse and my monster”. “She’s my monster primarily,” he says. “Coming into consciousness at the end of 1980s and early 1990s, Imelda was this really bizarre global cultural icon for conspicuous consumption. In some ways that trivialised her because you weren’t talking about state sponsored violence, you weren’t talking about how western banking structures enabled corruption on that scale, you were talking about shoes.”

Abad left the Philippines to study at Glasgow School of Art in 2004 on the advice of aunt, the artist Pacita Abad, and says the five years he spent in the city were crucial to his development. It was at GSA that he began to make the intricate ink drawings which are still an important part of his practice. It was also where he met his wife, jewellery designer Frances Wadsworth Jones, who is also his artistic collaborator. Their first child was born this summer.

“Any sense of possibility I had as an artist was shaped by those years at GSA,” he says. “At that time in Glasgow, in the remaining days of the Labour government, there was still a fair amount of cultural funding, so people were just making stuff. I did a little bit of assisting for Jim Lambie for a show he had at GoMA. I remember seeing an exhibition by Karla Black in a flat in Buchanan Street, and a few years later she was nominated for the Turner Prize.”

Studying for a Masters at the Royal Academy in 2010-2012, he began to research in depth the “loot” acquired by Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos, from rare jewellery to Old Master paintings and (at one point) the largest collection of Regency silverware in the world. The jewellery, in particular, became a source of fascination.

This evolved into a long-term project called The Collection of Jane Ryan and William Sanders - the false names under which the Marcoses opened Swiss bank accounts - which included remaking the missing jewels in collaboration with Frances, through digital 3-d printing. The jewellery, worth a reputed $21million, was smuggled out of the Philippines by the Marcoses when they fled in 1986 (to a safe house in Hawaii provided by the Reagan administration), but was seized by customs and returned to the Philippines. Now its whereabouts are unknown.

Abad’s collection of replicas was shown in the Philippines in 2022 at the time of the election which saw Ferdinand Marcos Jnr, the son of Ferdinand and Imelda, elected as President. “It’s been quite a journey, would be the understatement,” Abad says. “I think it was incredibly meaningful because this is a history that people know about but have never seen. A few days after the elections, the exhibition became a site for people to grieve, I think, and process what happened to the country. It was quite painful but quite beautiful. “I think people’s relationship to the work has shifted quite considerably. In a way, my profile as a Filipino artist has risen alongside the return of the Marcoses. So the very thing I guess I was trying to warn people about in my work has happened. In some ways the practice has been an abject political failure - but that’s okay!

“When Imelda Marcos was on trial in New York in the early 1990s, there was another figure who was a source of fascination: Donald Trump. They occupied the same space in popular culture where they were both symbols of extravagance, and that didn’t seem that menacing because they were just so crazy. And look where we are now!”

Abad seeks out much of his raw material in the back rooms of museums, from the Carnegie Collection in Pittsburgh to the Ronald Reagan Residential Archive in Simi Valley, California. He unfolds the stories objects tell, describing those in the Turner Prize show as “icons of loss, of personal grief, of colonial grief”. In the Ashmolean, he found a 17th-century etching of the “Painted Prince”, a young tattooed man taken as a slave from the Philippines and displayed in England as a curiosity. Then there’s diamond tiara once owned by the Russian Tsars, bought by Gladys Deacon, Duchess of Marlborough, in the 1920s, then later by Imelda Marcos.

.jpg) Pio Abad, I am singing a song that can only be borne after

losing a country, 2023. Red coloured pencil and carbon transfer on heritage wood free paper, 2400 x 1750 mm. Courtesy the artist© Pio Abad

Pio Abad, I am singing a song that can only be borne after

losing a country, 2023. Red coloured pencil and carbon transfer on heritage wood free paper, 2400 x 1750 mm. Courtesy the artist© Pio Abad

By reproducing and reimagining them, he makes the larger stories visible, not only about the Philippines but also the larger story of colonialism. “I think the history of the Marcoses and their cultural legacy will always be present in my work, but the Ashmolean show and now the Turner Prize show feels like a really fitting way to retain parts of that history that still feel relevant and find a way of weaving them with larger stories.” It’s a story which is never far from home, as Abad learned, quite literally, when he discovered that the building in which his apartment is located was once part of the Royal Arsenal Stores where the infamous British raid on Benin in 1897 - in which the Benin bronzes were looted - was planned and resourced. This inspired a series of detailed ink drawings juxtaposing images of the bronzes with ordinary objects from his home which also have uncomfortable histories: a rubber plant, a pile of books, a bag of sugar.

“To have my home implicated in that history was really powerful, and that became the catalyst to think about how the things, places and stories we contend with on a mundane level are deeply interwoven with larger histories of conquest, of violence. I look out of my window and see the first Tate & Lyle sugar factory: even the idea of sugar and where it comes from has shaped the view of the Thames and the city of London and the Turner Prize. It’s all woven in together.”

The Turner Prize Exhibition 2024 at Tate Britain runs until 16th February 2025. Tickets £14