Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

Ian Hamilton Finlay and Ian Gardner: A Walled Garden

By Greg Thomas, 12.03.2021

One of the less well-known facts about Ian Hamilton Finlay is that, for a short period from 1977 onwards, he was in semi-regular communication with the neoclassical architect and former Nazi Armaments minister Albert Speer. Indeed, it’s a fact that tends to be met with variously inflected forms of silence: silences of pre-emptive disapproval, or silences punctuated by the sound of sweeping. But Finlay’s use of the iconography and maxims of extremist politics, from the French Revolutionary Reign of Terror to the Third Reich, was a vital expression of his sense of conflict as an animating principle of culture. If we are to truly understand the agonistic aesthetics of this most significant of Scottish modernists, holding our silence on the motives for, and products of, his dialogue with Speer – whether or not we approve of it – is a difficult position to justify.

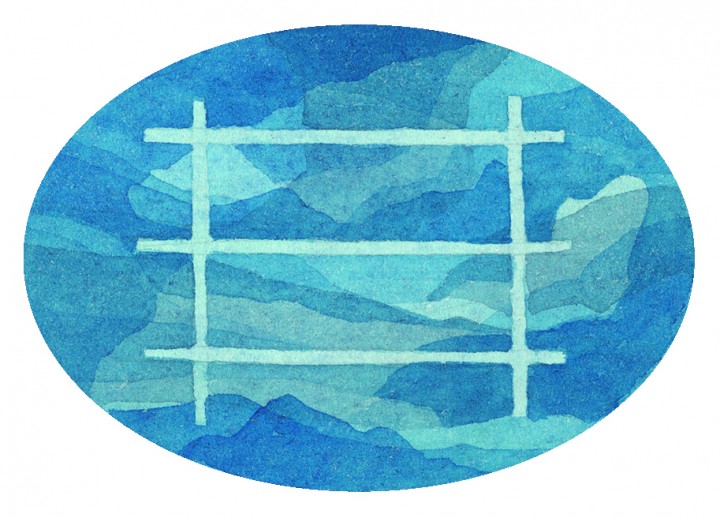

Ian Gardner, watercolour from Section 4, "The Secret Garden," in Ian Hamilton Finlay and Ian Gardner, A Walled Garden, Coracle and St. Paulinus Press, 2019.

Ian Gardner, watercolour from Section 4, "The Secret Garden," in Ian Hamilton Finlay and Ian Gardner, A Walled Garden, Coracle and St. Paulinus Press, 2019.

Coracle Press and St. Paulinas Press have recently taken the bold step of publishing the fruits of Finlay and Speer’s collaboration. A Walled Garden: A History of the Spandau Garden in the Time of the Architect Albert Speer was completed during the early 1980s but never released at the time. Whether this was due to Speer’s death in 1981, the considerable costs involved in realising the project, or the fact that Speer’s ‘Good Nazi’ mask (of which more below) was already beginning to slip in academic circles by this point, is unclear.

The book consists of a set of watercolours by the artist Ian Gardner – who died just prior to publication in November 2019 – depicting the gardens that Speer created in the grounds of Spandau Prison, during his 20-year sentence for war crimes and crimes against humanity. Speer’s gardening work was recorded in his international bestseller Spandau: The Secret Diaries, which Finlay read upon its publication in English in 1976, and which was the initial prompt for, and topic of, their correspondence. The watercolours, based on colour photographs sent with Speer’s letters to Finlay, are accompanied by quotes from the letters, outlining the scope and scale of the gardening project: “I conceived the idea of creating with bricks two sunken stone gardens which would satisfy my longing for architectural expression.” A postscript commentary provided by the literary critic Ross Hair unpacks with patient lucidity the layering of symbolic meaning through Finlay’s curation of text and image: from Heideggerian metaphysics via the linee occulte – dotted lines marking out imaginary volumes – of Renaissance architectural drawings to the philosophy of the Pre-Socratics.

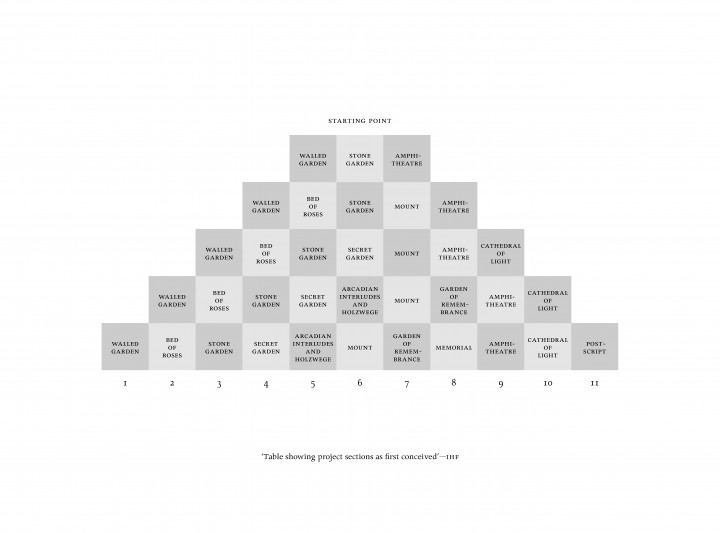

Ian Hamilton Finlay, "Table showing project section as first conceived," in Ian Hamilton Finlay and Ian Gardner, A Walled Garden, Coracle and St. Paulinus Press, 2019.

Ian Hamilton Finlay, "Table showing project section as first conceived," in Ian Hamilton Finlay and Ian Gardner, A Walled Garden, Coracle and St. Paulinus Press, 2019.

Knitting together all of these allusions is what Finlay called his ‘neo-Pre-Socratic’ or ‘Heraclitean’ sense of culture, aesthetics, and politics as animated by sets of mutually dependent opposing forces, most significantly in this case Classicism and Romanticism and War and Peace. By this reckoning, the miniature, organic architecture of Speer’s gardens becomes an expression of a redemptive Romantic aesthetic, realised on a human scale, which redefines the militaristic, Neo-classical gigantism of Speer’s Nazi-era projects. (Speer was, from 1934 until his appointment as Armaments Minister in 1942, Hitler’s favoured court architect, best-known for the “Cathedral of Light” effect which he conceived for the 1930s Nuremberg Rallies, using rows of upward-facing anti-aircraft lights.) The central visual metaphor involves a series of allusions between the miniature brick enclosures of Speer’s sunken stone gardens and the columns of the vast Zeppelintribune, which Speer constructed to enclose one end of the Nazi rally grounds at Nuremberg in 1934.

What were Finlay’s motives here? He was interested in gardens, was a gardener, and was also a chronic agoraphobic, bound to the grounds of his own garden at Little Sparta for over thirty years as Speer was imprisoned, more literally, at Spandau. Finlay was also a staunch critic of the politics and aesthetics of the post-war secular democratic consensus, a position on his part whose origins might reasonably be dated to 1966, the year he moved to Stonypath and Speer was released from Spandau. For all these reasons, there was perhaps some improbable sense of empathy at play in his relationship with Speer. Finlay was also interested in placing images of contemporary technological warfare in the redemptive light of classical and historical analogy: as if such analogy might grant some quality of narrative clarity or meaning to the bloodshed and genocide which had defined the era he had lived through.

Ian Gardner, watercolour from Section 11, "Postscript," in Ian Hamilton Finlay and Ian Gardner, A Walled Garden, Coracle and St. Paulinus Press, 2019.

Ian Gardner, watercolour from Section 11, "Postscript," in Ian Hamilton Finlay and Ian Gardner, A Walled Garden, Coracle and St. Paulinus Press, 2019.

Nonetheless, it is worth acknowledging at this point that the presentation of Speer’s gardens as symbols of aesthetic, political, even ethical redemption seems to let their architect off the hook all too easily for the grotesque crimes in which he was implicated. Gardner’s watercolours seem, to us, in 2020, sinister precisely in their sweet evocation of a Romantic idyll shielded from the context of its realisation (bar a few images of the guard tower in Section 11, “The Mount”, which make more of Speer’s imprisonment than the reasons for it). On that note, it is worth recalling, on the one hand, Finlay’s justified sinner interest in incurring the wrath of liberal secular audiences, and on the other, Speer’s remarkable and entirely mendacious post-war reinvention of himself, through his Spandau diaries and another bestselling memoir, Inside The Third Reich, as an apolitical technocrat. By this reading, little questioned at the time outside academic circles despite Speer’s obvious motives for lying, he remained largely oblivious of the crimes the Nazi regime was perpetrating even as one of its lead ministers, and would rather have remained a simple exponent of the international neo-classical architectural revival of the 1920s-30s (that this revival accompanied the era of the International Style worldwide, and was not simply an aberration of Nazi aesthetics, is often forgotten.) The myth of ‘The Good Nazi’, as Speer came to be known, was remarkably tenacious, and was at the height of its power when Finlay first contacted him.

Ian Gardner, watercolour in Ian Hamilton Finlay and Ian Gardner, A Walled Garden, Coracle and St. Paulinus Press, 2019.

Ian Gardner, watercolour in Ian Hamilton Finlay and Ian Gardner, A Walled Garden, Coracle and St. Paulinus Press, 2019.

Even at the time, of course, the myth had its sceptics, and many might have questioned Finlay’s willingness to communicate with a figure such as Speer to gather material for his art. It is, in part, precisely to keep questions like this alive that this book deserves attention, regardless of its undoubted merits as a work of fine art publishing, and the gorgeous clarity of Gardner’s watercolours. A Walled Garden is an expression of a complex, trenchant worldview, and Finlay’s burgeoning ‘national treasure’ status should not silence discussion on the thornier aspects of his legacy: which, after all, he left his audiences open invitations to consider. For this reason and many more, this work deserves our attention.

'A Walled Garden' is published by Coracle and Saint Paulinas Press, 2019