Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

Hill-walking for the Eyes

By Greg Thomas, 02.03.2022

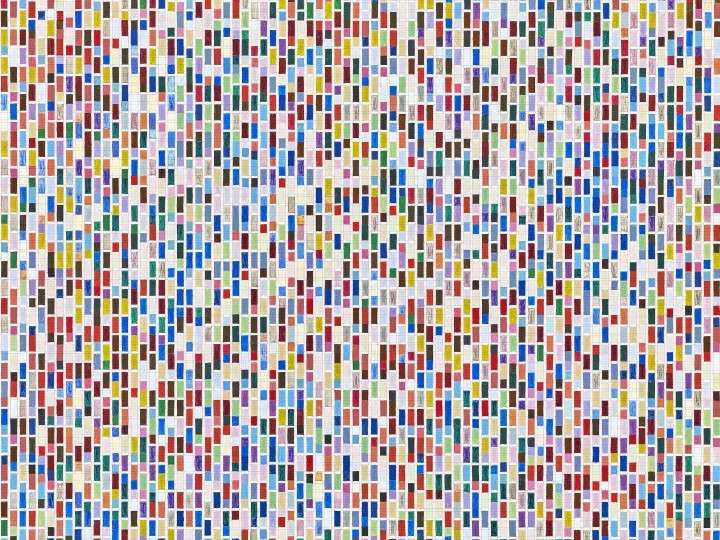

James Hugonin (b. 1950) has spent the last four decades perfecting a process of minimalist mark-making, applying tiny squares or rectangles of wax-thinned oil paint over large canvas grids. The set of seven paintings now on show at Edinburgh’s Ingleby Gallery marks the culmination of his latest series Fluctuations in Elliptical Form. These works are created on the largest scale so far attempted in the artist’s career, with each a little over two metres in height.

Hugonin and his partner, artist Sarah Bray, live in the Cheviot Hills just below the Scottish border, and the light of the Northumbrian landscape has seeped into Hugonin’s palette over the years, with works from the 1980s-2000s achieving a rhapsodic translucency in which the viewer gently relaxes into the recognition of minute colour increments. More recently, as the Ingleby notes, “tonally weighty marks of more solid colour” have made their mark, with the current series divided into four pairs, each comprising a ‘warmer’ and ‘cooler’ sibling. This effect is achieved through swapping the colours – blue and pink – used to form the vertical and horizontal lines of the underlying grid. Like so much about Hugonin’s practice, its effects impress themselves slowly but certainly on the mind and eye.

A beautiful essay by neuroscientist Anya Hurlbert has been produced to accompany the Fluctuations series, outlining the complex system by which the colour and placement of each minute quadrilateral was determined. Simply put, this involves applying colours from one of eight groups of six (with 41 additional tones also used) using an elliptical template moved according to one of a set of pre-determined patterns – think chess moves – across the canvas. Eventually, towards the end of each composition process – which takes a year on average – intuition comes to dominate, and the artist foregoes the system for muscle memory or subconscious instinct, ensuring that the colours cluster and dazzle in a consistent or pleasing manner across the picture-surface.

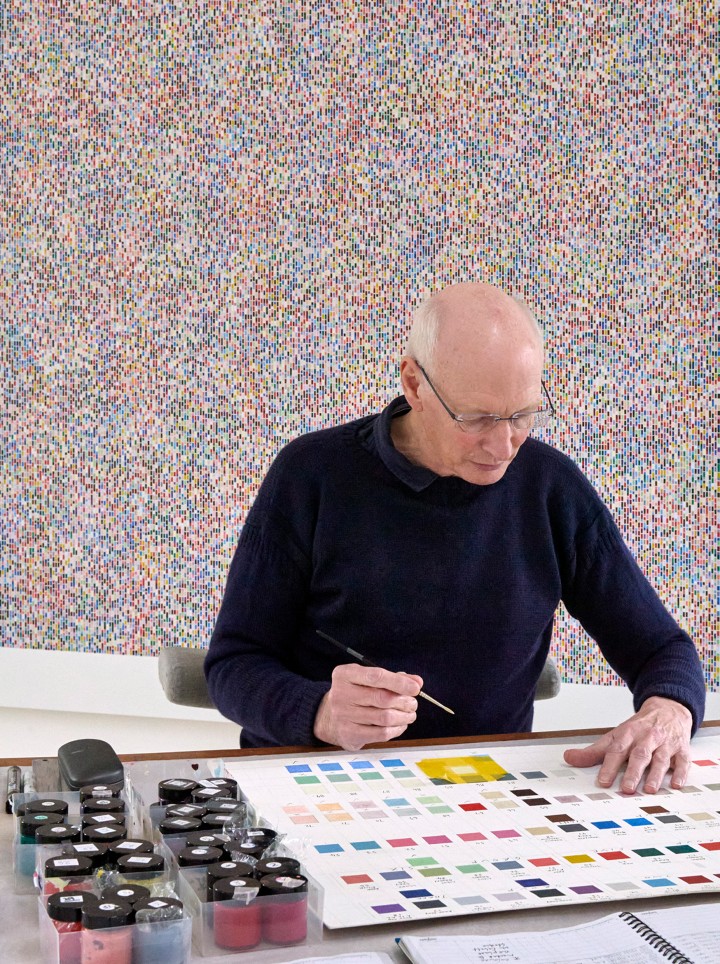

James Hugonin in the studio, 2021. Photograph: John McKenzie.

James Hugonin in the studio, 2021. Photograph: John McKenzie.

At the root of this decision to intercede in the formula is, ironically, Hugonin’s desire that no figurative form should appear in the finished product: “I don’t want there to be any Christmas trees or swastikas in the paintings, no dogs or cats”, Hurlbert quotes him as saying. Yet as she herself adds, “that does not stop people from seeing whatever else they want.”

My own encounter with these works is as gently, generously mesmerising. The influence of Pointillism – whereby the visual cortex is invited to reconcile a series of dots, strokes, or marks into solid blocks of colour – gently brushes against the effects of Op Art, where static forms are experienced as motile, colours as impacted by the spectral range around them. We are at once encouraged to draw simplifying patterns and cognisant of a complicating, hallucinatory impulse. An initial sense of the whole as a topographical terrain, of an aerial landscape of falling and rising hillsides, gives way to a backlit scattering of scorch-lines, like subtle retinal disturbance. Each piece briefly seems to resemble a four panelled window or even a crucifix—though here I veer too close, perhaps, to the illustrative suggestions the artist seeks to avoid.

Hugonin is a minimalist artist of the first order. More invested in detail than Agnes Martin, less with the brilliantly extravagant optical trickery of Bridget Riley or Victor Vasarely, his work plies a consistent furrow with quiet certainty. The results are mind expending. Yet, with the differences of scale that they involve, it is imperative that they are viewed in person for their impact to be appreciated.

Installation view of James Hugonin's solo exhibition, Fluctuations in Elliptical Form, at Ingleby. Photograph: John McKenzie.

Installation view of James Hugonin's solo exhibition, Fluctuations in Elliptical Form, at Ingleby. Photograph: John McKenzie.

James Hugonin’s exhibition Fluctuations in Elliptical Form is showing at Ingleby until Saturday 26th March.