Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

Hidden depths: Edwin Morgan’s scrapbooks

By Greg Thomas, 19.10.2020

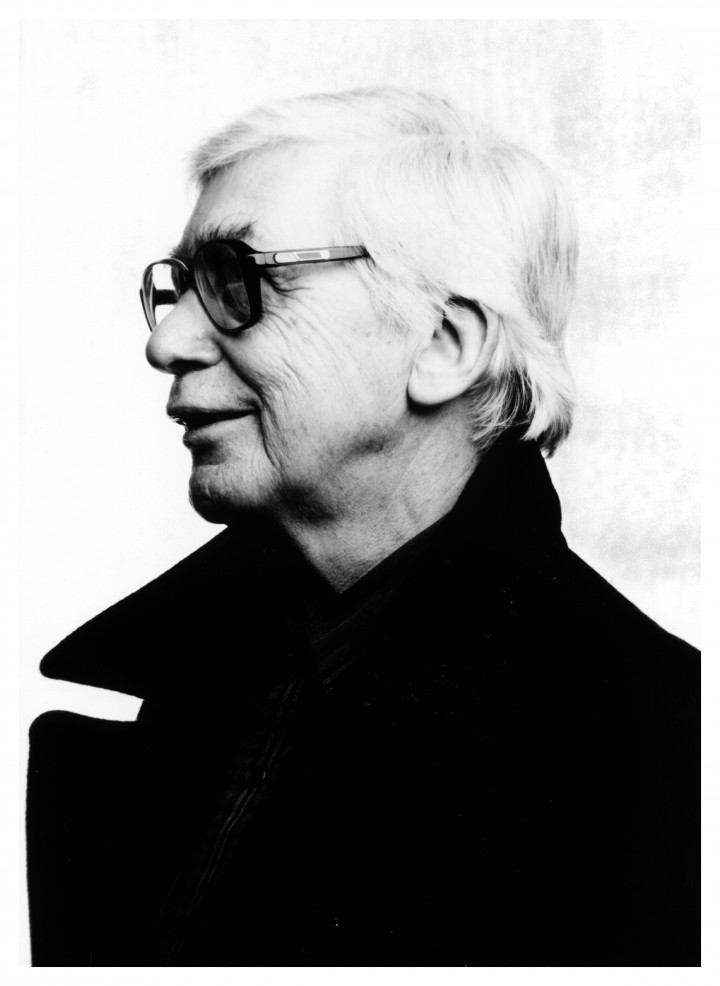

Edwin Morgan remains a difficult poet to categorise. Celebrated as a documenter of social realities, he once proposed the arch-modernist J.H. Prynne as the UK’s Poet Laureate. A lifelong advocate of Scottish nationalism, he spent much of his career rebuffing parochial Scottish exceptionalism. Architect of impersonal concrete poems and escapist sci-fi fantasies, the best-known works in his breakthrough collection The Second Life (1968) were achingly sweet love poems, addressed to an anonymous lover only latterly revealed to be male (Morgan came out in 1990, as a ‘seventieth birthday present to himself’).

One thing that might seem clear is that Morgan was, first and foremost, a poet, and not a visual artist. Yet the contents of his “scrapbooks” – the common term of reference sums up nothing of their Surrealist splendour – troubles even that distinction. Morgan began assembling these huge volumes of collaged word and image in 1931 or 1932, as a bright, somewhat solitary prepubescent boy, living with his middle-class Presbyterian parents in Rutherglen. By the time Morgan stopped working on the scrapbooks, in 1966, the world had changed and so had he: he was a poet and critic living in a new-build flat in Glasgow’s west end, recently embarked on a life-defining romance, and composing the adventurous, genre-traversing work that would make him famous.

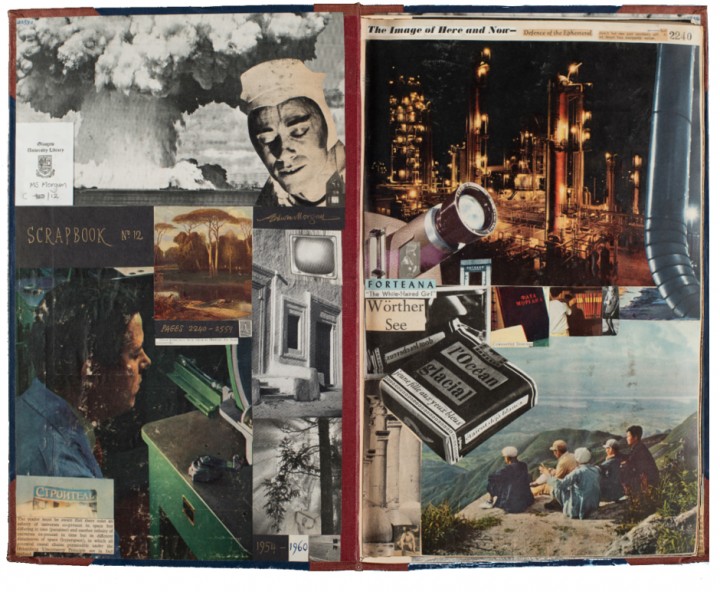

The method of assemblage used for the scrapbooks involved pasting text and image from newspapers, science and nature magazines, and academic textbooks alongside Morgan’s own sketches, abstract designs, and occasional prose entries. There is also a smattering of personal photographs, and endless passages of poetry, many of them ripped directly from books. Morgan described the cumulative effect in a 1953 letter to the literary agents Christy and Moore, whom he hoped would find a publisher for the sprawling and still-growing collection: “partly documentary/historical, partly aesthetic, partly satirical and partly personal . . . a Whitmanian reflecting glass of ‘the world' as refracted through one personality.”[1]

Edwin Morgan, Scrapbook 12. Courtesy R. Deazley, K. Patterson and V. Stobo, Digitising the Edwin Morgan Scrapbooks (2017), www.digitisingmorgan.org.

Edwin Morgan, Scrapbook 12. Courtesy R. Deazley, K. Patterson and V. Stobo, Digitising the Edwin Morgan Scrapbooks (2017), www.digitisingmorgan.org.

As this summary would suggest, if any organising principle can be attributed to the scrapbooks, it is one that fits Tristan Tzara’s description of cut-up logic: “the poem will resemble you.” Morgan gave free rein to the instinctive or compulsive aspects of his imagination in determining the content and structure of the works. As such, they seem to chart an uncertain course between social documentary, gnomic visual collage, and photo diary, while simultaneously tracing the most significant scientific, social, economic, and artistic trends of the mid-twentieth century. They serve no conscious function, but form a protean imprint of the poet’s mind.

The topics broached and compositional methods utilised across the sixteen volumes are too varied to list, but certain themes recur. Animals, architecture, religion, and artificial intelligence will be familiar topics to Morgan’s readers, while the political and ethical animus of his writing is reflected in collages from the post-1945 years reflecting an impending sense of dread about the nuclear arms race.

Influences are as hard to pin down as narrative through-lines, but we know that Morgan loved the Surrealist Art of the 1930s and the New Apocalypse poetry that took inspiration from it, particularly the work of Dylan Thomas and Morgan’s friend W.S. Graham. Much of the scrapbooks’ impression of submerged meaning seems to take its cue from that movement, while the interaction of text and image predicts, without necessarily partaking of, developments in British Pop Art in the 1950s and Concrete Poetry in the 1960s.

In Morgan’s centenary year we continue to celebrate his searching and humane intelligence. His scrapbooks, now stored with his personal papers in Archives & Special Collections at the University of Glasgow Library, provide boundless depths of material for anyone seeking to excavate a singular creative character.

View images of the Scrapbooks at digitisingmorgan.org, which provides additional context for the pages’ composition and a copyright statement. R. Deazley, K. Patterson and V. Stobo, Digitising the Edwin Morgan Scrapbooks (2017).

[1] This quote is from James McGonigal and Sarah Hepworth’s 2012 article “Ana, Morgana, Morganiana: A Poet’s Scrapbooks as Emblems of Identity,” published in issue 2.4 of Scottish Literary Review.