Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

Helen Flockhart: Beasts

By Susan Mansfield, 02.12.2020

Start talking to Helen Flockhart about her latest exhibition and it’s not long before she hauls up a pile of books from the floor beside her desk. She holds them up one by one: Mary Beard’s Women and Power, Madeleine Miller’s highly acclaimed retelling of the Circe myth, Gerda Stevenson’s poetry collection Quines. To make ‘Beasts’, which recently opened at the Arusha Gallery in Edinburgh, Flockhart dived deep into a world of myths and stories.

In these depths, an image or a line of description might surface and inspire a painting. As with her acclaimed exhibition about Mary Queen of Scots, ‘Linger Awhile’, which was shown at Arusha and Linlithgow Burgh Halls in 2018, she doesn’t focus on the main events of the story. Her finely wrought paintings capture moments which have a life of their own.

‘It’s not an illustration of a myth or a story, it’s really just a germ of an idea which leads into its own story,’ she says. ‘It starts when an image suggests itself from the side of your brain. It might just be a memory of a story which I’ve known a fragment about. You take that and it goes off on its own track, becomes its own little world.’

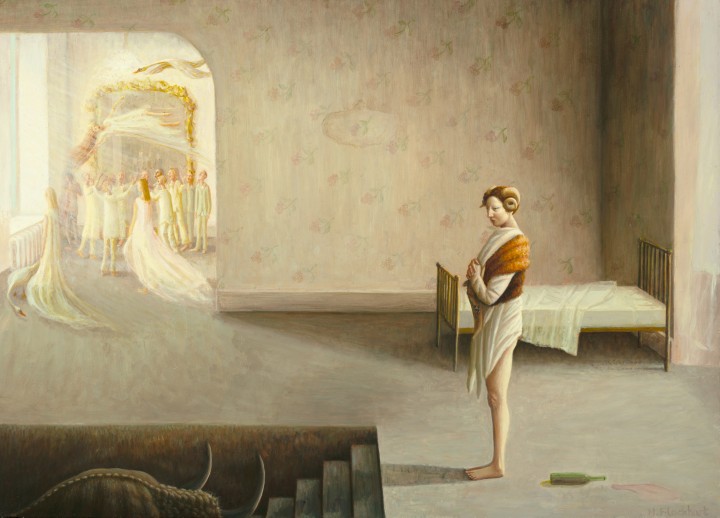

Helen Flockhart, Reckoning, 2020, Oil on panel, 26 x 40 cm. © the Artist.

Helen Flockhart, Reckoning, 2020, Oil on panel, 26 x 40 cm. © the Artist.

Her dramas, which often take place against a backdrop of richly patterned foliage (Flockhart loves the paintings of Henri Rousseau), are often populated by women and animals. Minotaurs recur in this show, but they are figures of pathos rather than menace. ‘I really empathise with the minotaur, his tale was quite poignant. He didn’t ask to be born, but he was born with an insatiable lust for human flesh and was incarcerated for his whole life.’

The character of Circe, the island-bound enchantress of Greek mythology, captured Flockhart’s imagination right away. ‘She used her craft to sustain herself and defend herself, used the powers she had. I empathise with her because she was such an outsider, she wasn’t particularly beautiful, she didn’t have a lovely voice and she had eyes the colour of piss. She was jealous and turned her love rival into a sea monster. I related to the fact that she’s flawed.’

Flockhart says she doesn’t set out to offer a feminist reworking of myths. ‘But looking back on the paintings, a lot of them are dealing with how people have interpreted stories, and maybe I’m turning them round so that the women don’t appear so much like victims, but are fighting back a little bit.’ And there is often an eye on the present, too: women still vulnerable to violence, or easily demonised, like Hillary Clinton caricatured as Medusa.

Helen Flockhart, Eve, 2019, Oil on board, 28.5 x 36 cm. © the Artist.

Helen Flockhart, Eve, 2019, Oil on board, 28.5 x 36 cm. © the Artist.

In her painting of Eve, the protagonist is stretched out languidly on the back of a zebra, gazing up at the sky. ‘It was quite a playful idea, that she’s cutting about the garden not too burdened by what’s going to become an onerous legacy of hers. Eve has got a bit of a raw deal, there’s an awful lot put on her shoulders, so I was letting her have a bit of fun. She’s thumbing her nose a bit, in that painting.’

Flockhart grew up in Ayrshire and studied at Glasgow School of Art, just as the New Glasgow Boys - Peter Howson, Adrian Wiszniewski, Ken Currie and Steven Campbell - were emerging stars. The energy in figurative painting at the time would be described as large-scale and macho, but women were part of it too. Flockhart began painting symbolist landscapes in which figures gradually gained importance. Over the years, her work has become smaller, tighter, more decorative, more consciously feminine.

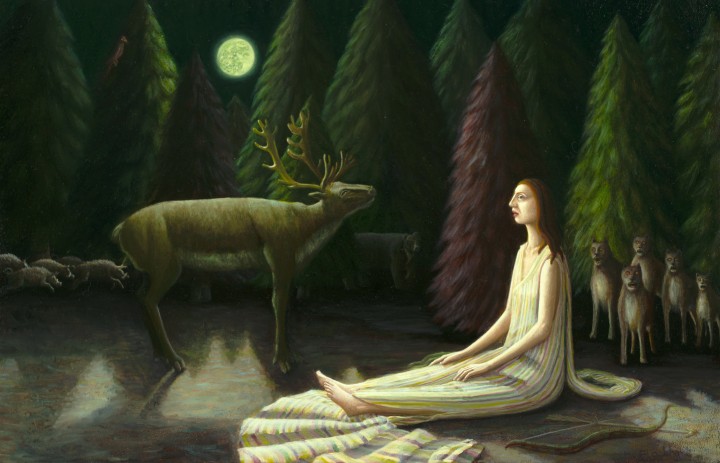

Helen Flockhart, Lady of the Beasts, 2020, Oil on panel, 26 x 40 cm. © the Artist.

Helen Flockhart, Lady of the Beasts, 2020, Oil on panel, 26 x 40 cm. © the Artist.

Each work begins with a tiny pencil sketch of abstract shapes, with the finished painting built up slowly in layers. A larger work can take several months to complete. ‘I’m trying to keep the immediacy of that little sketch, the essence of whatever that flash was in my brain. You’re trying to pay attention and at the same time not pay attention to that flickering image you have at the back of your head.’

‘It’s a very instinctive process, and it’s a bit like pulling teeth. It doesn’t really get any easier. I’ll resolve what I know how to resolve, and then those bits will suggest what should be in the other areas. There’s always a point where you think it looks awful, you’ve got to have faith in the energy of that little sketch and remember there was a reason why you thought this was worth doing.’

She says if she had not been invited to show in Linlithgow Burgh Halls, she might never have explored the story of Mary Queen of Scots, in which she quickly became immersed. Like Eve, or Circe, Mary is a woman trapped by the myths which grew up around her. ‘It’s the way she’s perceived, and the way her myth has been manipulated, in the way that a lot of myths are. The way these stories are remembered and how people use these tropes and stereotypes tell me a lot about attitudes now.’

Helen Flockhart: Beasts is at Arusha Gallery, 26 November - 20 December