Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

Germany Calling! - How Strategy: Get Arts Enlightened Edinburgh

By Neil Cooper, 06.10.2021

Action! Time! Vision!

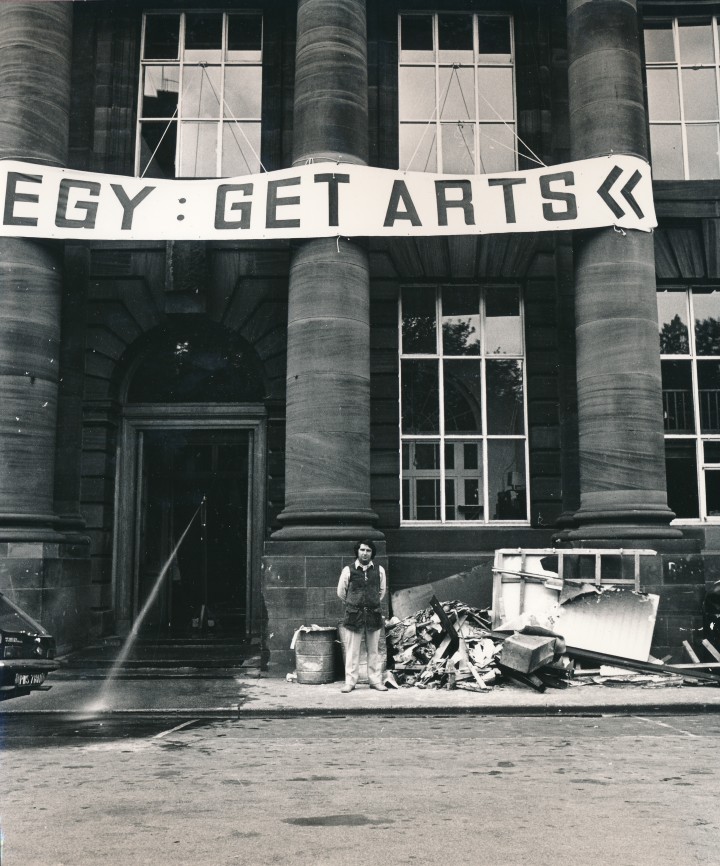

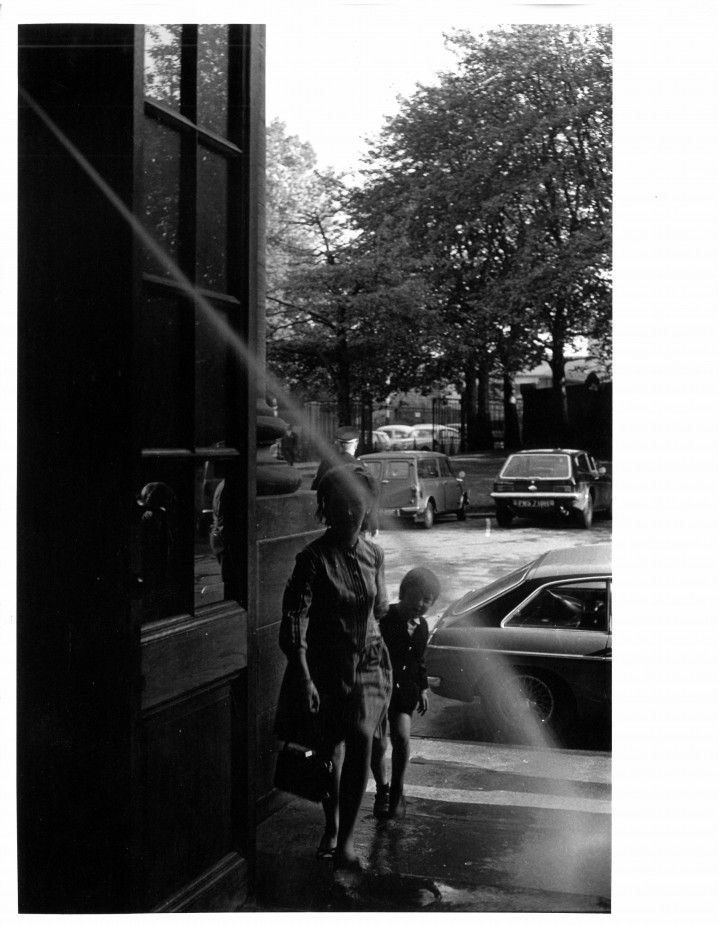

It was fifty-one years and a little bit more ago today that 'Strategy: Get Arts' (SGA) opened its doors at Edinburgh College of Art with a splash. The latter came care of Klaus Rinke’s water installation hosing people down as they entered ECA’s main building during the exhibition’s three-week run during Edinburgh International Festival from late August to mid September 1970. Since then, the ripples of this now legendary conceptualist infiltration of ECA’s historically staid environs by 35 Düsseldorf based artists has arguably helped open up, not just its host city, but the entire world it turned upside down.

Just how much the palindromically named extravaganza left its mark is clear from Christian Weikop’s forensically researched new book, Strategy: Get Arts – 35 Artists Who Broke the Rules. The book was launched in August at the 2021 Edinburgh International Book Festival, at an event in ECA’s Sculpture Court. It was here and in the rooms around it that work by Joseph Beuys, Gerhard Richter and 33 others once held court, only to have their presence all but erased from official history shortly afterwards.

As a senior lecturer in modern and contemporary German art at ECA, now part of the University of Edinburgh, Weikop does much to reclaim SGA's seismic impact. This is realised through a series of essays that chart the before, during and after of the exhibition. These are set alongside an evocative series of photographs by Monika Baumgartl, Ute Klophaus, George Oliver and Richard Demarco that capture the energised whirl of activity around the show. The only person who seems to be standing still in the images is Beuys, who maintains a beatific calm as the world appears to revolve around him.

Richard Demarco certainly seemed to think so. It was the questing arts impresario on the frontline of Edinburgh’s 1960s avant-garde, after all, who instigated what would become SGA, presented by his gallery in association with Kunsthalle Düsseldorf. Demarco’s tireless mix of chutzpah, hustling and international networking a-go-go were instrumental in pulling the event together. The practical navigations of his administrator, artist and writer Jennifer Gough-Cooper, were just as vital. Gough-Cooper has provided a text for Weikop’s book, and photographs from her archives appear in it.

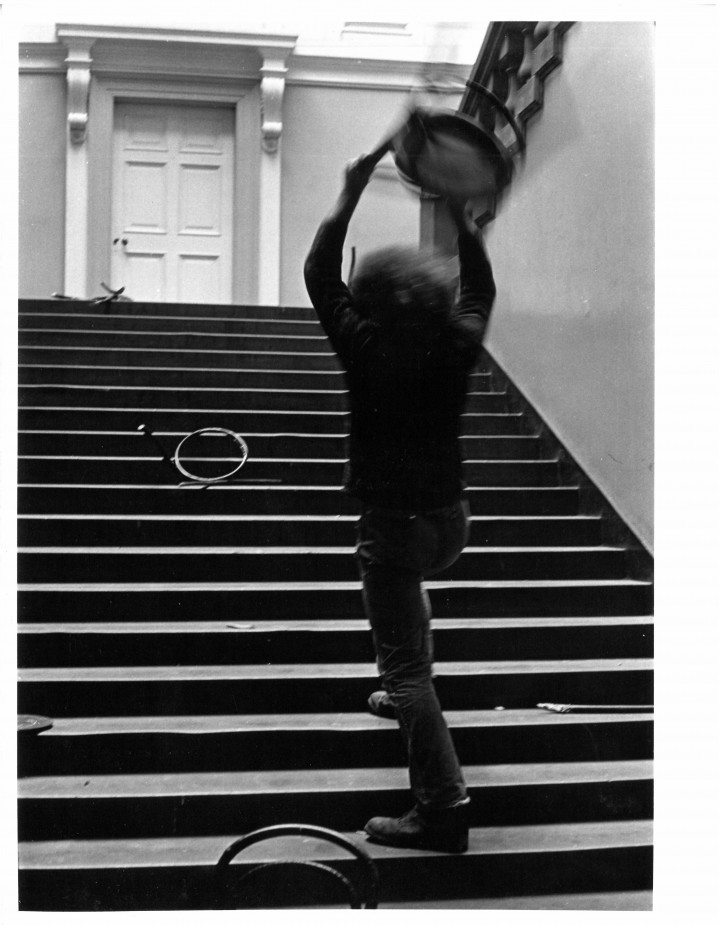

Weikop’s discourse charts SGA’s rapid-fire journey, from Demarco’s initial idea, to the wing and a prayer chaos of bringing it to fruition mere months later. Perhaps most significant of all are the intangible life-changing effect of the exhibition on those who either witnessed it or helped make it happen, which Weikop and others point towards. If a picture paints a thousand words, then Oliver’s front cover image of Rinke in the throes of smashing a chair on ECA’s main building steps as part of Stefan Wewerkas’s Bentwood Chairs Action speaks volumes. It also sets the frame-busting tone of things to come.

Klaus Rinke’s water jet at the entrance to ECA Main Building (August 1970). Photo © George Oliver.

Klaus Rinke’s water jet at the entrance to ECA Main Building (August 1970). Photo © George Oliver.

Edinburgh: So Much to Answer For

‘Dada for the seventies’ read the headline to an article on SGA by Edinburgh-based art critic Cordelia Oliver. ‘More impact than the Venice Biennale’ declaimed her counterpart at the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (FAZ), Georg Jappe. Both are quoted by Weikop, as are the opening lines from a group discussion between SGA’s contributing artists that took place in the Düsseldorfstudio of Gunther Ueker a month before the exhibition opened.

Ueker, along with Gerhard Richter, had been tasked with rounding up Düsseldorf’s finest with a view to taking part in SGA. The dialogue between Karl Gerstner and Wewerka opened the full transcript of a conversation originally published in John Martin’s groovily designed large-size exhibition brochure/catalogue, latterly republished by Demarco as a facsimile edition in 2005. The laddish banter between the two artists in this predominantly male affair shows just how moribund Edinburgh in 1970 was perceived to be.

‘Gerstner: I have no idea of Edinburgh except that every year there is a terribly boring Festival there. Wewerka: Weren’t we going to de-bore it a bit?’

On reflection, Gerstner and Wewerka’s cocksure bravado was probably a tad unfair. By the time their comments were recorded, the Traverse Theatre had been presenting the European avant-garde and homegrown fare to adventurous theatre audiences in a former brothel off the High Street for more than half a decade.

The Traverse had been set up following a meeting of minds after American ex GI Jim Haynes had started selling previously off-limits literature from his Paperback Bookshop, on Charles Street, later demolished by the University of Edinburgh. Haynes’ sense of cultural internationalism was aligned with Demarco’s own, and both were key players in the founding of the Traverse.

Meanwhile, Allan Kaprow had livened up the 1963 International Drama Conference at the McEwan Hall with a 'Happening', while Scotland’s burgeoning folk music revival had gradually taken a psychedelic turn by way of The Incredible String Band.

Even so, SGA was still a shock to a system that indulged such things for a couple of weeks in August, before Edinburgh’s presbyterian gloom washed over the city once more. In this sense, there is the feeling that SGA represented those trying to break on through existing orthodoxies, and who were doing their thing in part to cock a snook at the old order rather than being absorbed by it.

This notion that anything was possible runs throughout Strategy: Get Arts – 35 Artists Who Broke the Rules. Weikop quotes Edward Lucie-Smith’s Sunday Times review of SGA, which was published under the heading ‘A great subversive’. Lucie-Smith wrote that ‘The Demarco-Düsseldorf show is shock tactics; it makes most English artists look provincial. It even makes the New York avant-grade look tame…’

Klaus Rinke participating in Stefan Wewerka’s bentwood chairs action on the staircase of ECA Main Building (August 1970). Photo © George Oliver.

Klaus Rinke participating in Stefan Wewerka’s bentwood chairs action on the staircase of ECA Main Building (August 1970). Photo © George Oliver.

Beuys, Beuys, Beuys… And More?

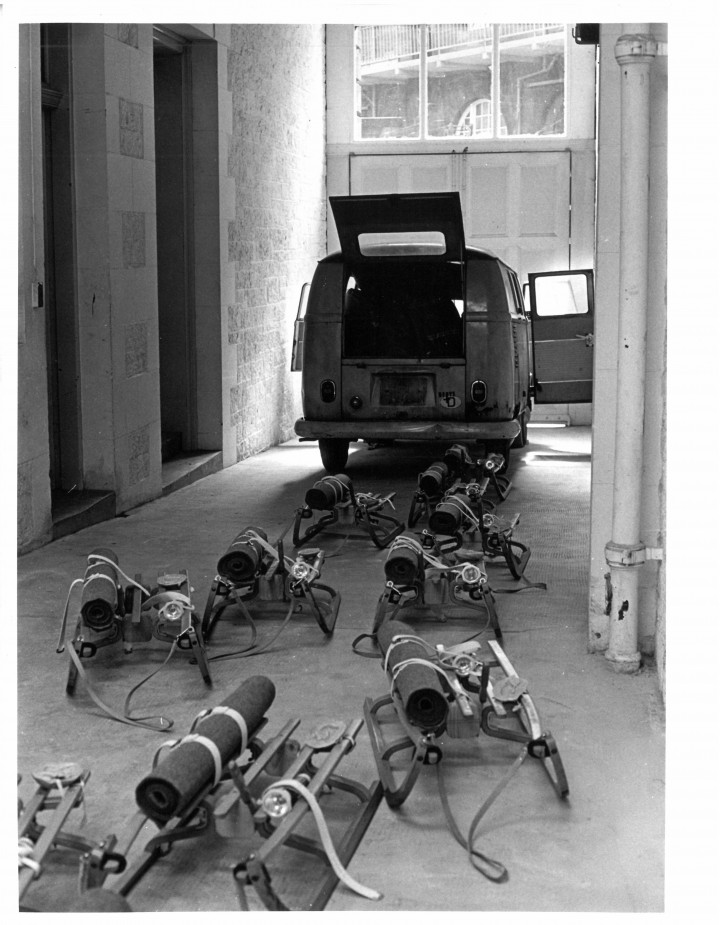

According to legend, it was Joseph Beuys who was the star of SGA. Beuys’ undoubted charismatic presence is immortalised in situ in some of the images contained in Weikop’s book. His now seminal SGA works, The Pack (1969) – a VW van with sledges attached to the back – and Celtic (Kinloch Rannoch) Scottish Symphony (1970) - an action in collaboration with Danish Fluxus composer Henning Christianson - led to several return visits to Edinburgh throughout the 1970s. These came care of Demarco’s long-term lionisation of the artist and his work. As the title of Weikop’s book makes clear, however, the exhibition was about much more than Beuys alone.

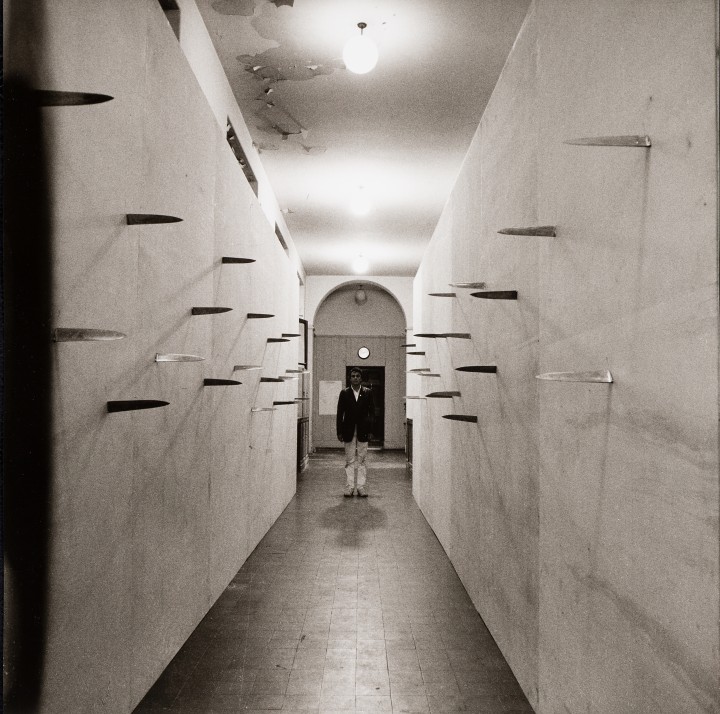

With SGA’s opening salvo coming from Rinke’s water installation on the way in to ECA, the various rooms contained works that might have similarly been drawn from a fun fair freakout. If Wewerker’s smashed up chairs on the stairs weren’t enough, there was Uecker’s corridor of knives, a series of butchers knives sticking out from the walls of the corridor leading to ECA’s Sculpture department. As Weikop recounts, the police insisted on the knives being covered up, which Uecker responded to with a self-mythologising banner declaring ‘SHARP CORRIDOR BLUNTED BY POLICE’.

These days, Gotthard Graubner’s Mist Room (Homage to Turner) might be dubbed ‘immersive’ or ‘experiential’. At SGA, however, it almost caused the collapse of the entire exhibition after the local fire service was called in to put out an accidental blaze caused by the work. The firemen captured in action in Weikop’s book saved the day, but between the Mist Room fire and Rinke’s water installation, the elemental forces powering SGA were great, however unintended they might have been.

Joseph Beuys, The Pack, installed for Strategy: Get Arts (August 1970).

Photo © George Oliver, © DACS 2021.

Joseph Beuys, The Pack, installed for Strategy: Get Arts (August 1970).

Photo © George Oliver, © DACS 2021.

Those Were the Days, My Friend

One other element of SGA was a noticeable dearth of women artists. Out of the exhibition’s 35 participants, only two were women. One of these, Hilla Becher, was showing work as part of a dual practice with her husband, Bernd Becher. The other, Dorothy Iannone, flew solo, though it may or may not be significant that the American born artist was at the time living with Dieter Roth, whose work was also included in SGA.

The Bechers’ contribution to SGA was two versions of typological grids of pitheads the couple dubbed Anonymous Sculptures. George Oliver’s images of them are referred to in Weikop’s book as Pitheads. The two photographs presented don’t exactly do the pair’s images justice, with them being either hidden or else overshadowed by other works in the pictures.

Weikop quotes historian and curator Karen Barber’s observation that all photographs of Anonymous Sculptures taken at SGA are ‘obscured in every instance’, and that ‘the work that would be the most consequential for contemporary photography seems to have elicited the least attention’.

If the stately quietude of the Bechers’ images didn’t sit as excitingly for those documenting SGA as the sturm und drang of much else on show, a distinctly local resonance seems to have been missed. The Scottish office of the National Coal Board was a stone’s throw from ECA on the corner of Lauriston Place, and the organisation’s head did the honours at the exhibition’s opening. With this in mind, perhaps Berndt and Hilla Bechers’ fascination with industrial architecture within the British coal industry was too close to its own doorstep. Given that the structures pictured by them are likely to be long gone now, history has given them a monumental depth perhaps not recognised at SGA.

Where the Bechers’ work went largely unnoticed at the time, Iannone’s contribution to SGA failed to attract the headlines for different reasons. Given her track record, this wasn’t what those behind the exhibition might have expected. As outlined by Weikop, Iannone’s work was inspired by Japanese woodcuts, Tibetan Buddhism and Indian Tantrism. Often autobiographical in tone, her paintings, drawings and texts could be sexually explicit, complete with depictions of male and female genitals on show.

A year before, Kunsthalle Bern had asked Iannone to cover up the vital parts of images shown in an exhibition also featuring work by Roth. Daniel Spoerri, Andre Thomkins and Karl Gerstner all took part as well. All of these went on to feature in SGA, with Thomkins gifting the show its title. Back in Bern, Roth threatened to withdraw if Iannone was censored. Protests, unrest and resignations ensued.

As Weikop recounts, Iannone’s contribution to SGA included The Story of Bern (1970), an artist book telling the story of what had transpired through sixty-nine drawings. Many of these laid bare the very things the authorities had objected to in the first place. Artists and students at SGA girded their loins for a protest similar to that in Bern if the police or anyone else attempted to remove, ban or cancel Iannone’s drawings. Any potential for scandal was something of an anti-climax, alas, as the authorities either failed to notice or else didn’t mind Iannone’s images, and went for the jugular of Uecker’s wall of knives instead.

Becher and Iannone’s presence at SGA was nevertheless significant in terms of breaking through the Beuys club that reflected much of the era’s displays of counter cultural activity. Those really were the days, my friend.

Günther Uecker in his Sharp Corridor at ECA (August 1970). Photo © Monika Baumgartl. © Günther Uecker. All rights reserved. DACS 2021.

Günther Uecker in his Sharp Corridor at ECA (August 1970). Photo © Monika Baumgartl. © Günther Uecker. All rights reserved. DACS 2021.

Messing Up the Paintwork

Arguably the biggest cause celebre of SGA was Blau/Gelb/Weiss/Rot (1970), by Blinky Palermo. This multicoloured architrave intervention saw Palermo precariously perched at the top of a ladder in ECA’s main building as he painted each side blue (north), yellow (east), white (south) and red (west). As ECA’s Professor of Visual Culture Andrew Patrizio puts it in his contribution to Weikop’s book, ‘The performative heroism of Palermo’s effort in August 1970 marks a lost world - one that existed after the fall of the classical gods yet before the rise of the health and safety officer’.

Such heroism, alas, couldn’t prevent Palermo’s efforts being literally and metaphorically whitewashed out of existence by the powers that be once Palermo and his band of hippy anarchist vandals had left the building.

Patrizio documents his and others efforts to restore what he calls ‘a great lost work of the neo-avant-garde’ by way of Palermo Restore (2005). As Patrizio recalls, this initiative led to an archival Palermo exhibition at the University of Edinburgh’s Talbot Rice Gallery, a conference, and what Patrizio describes as a painted ‘homage’ to the original Blau/Gelb/Weiss/Rot. An accompanying exhibition, Strategy: Get Arts Revisited (2005), was held at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art.

A decade on, a small archive of documents, letters, photographs and other ephemera relating to SGA was shown in the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art’s Keiller Library in the gallery’s Modern Two building. As National Galleries of Scotland archivist of modern and contemporary art Kirstie Meehan recounts in her contribution to Weikop’s book, this coincided with two other exhibitions. The first, 'ARTIST ROOMS: Joseph Beuys – A Language of Drawing', occupied the whole of the building’s top floor. The second, 'Richard Demarco and Joseph Beuys – A Unique Partnership', took over the Penrose Gallery on the ground floor. Institutional acceptance for SGA, it seemed, had come at last.

Blinky Palermo making his wall painting Blue/Yellow/White/Red (August 1970). Photo © Monika Baumgartl. © DACS 2021.

Blinky Palermo making his wall painting Blue/Yellow/White/Red (August 1970). Photo © Monika Baumgartl. © DACS 2021.

Shock of the Neu!

While each artist taking part in SGA brought their own disparate individual practice to bear, there was something about its collective whole pushing beyond the boundaries of regular group show narratives that captured the spirit of the times. Weikop touches on this in his mention of the 1968 anti establishment global uprisings that caught the political and artistic imaginations. With this in mind, beyond Weikop’s necessary focus on the story of SGA itself, there existed a synchronicity of sorts with parallel activities in other art forms that seemed to come from the same place spiritually as much as geographic proximity.

In terms of a physical manifestation of this, Düsseldorf was clearly where it was at, art-wise. As with any other city’s various scenes, there existed an intangible synergy, and an unspoken mutual desire to push boundaries and move ever forward. If something more holistic and harder to pin down was at play, any sense of taboo-busting iconoclasm at SGA likely emanated from the ruins of Germany’s recent past. As Weikop notes in the introduction to his book, SGA was the first exhibition of German contemporary art to be seen in Britain since 1938.

During the decades leading up to SGA, post-World War Two Germany was in the throes of attempting to reinvent itself beyond the shame of its Nazi past into something more progressive and enlightened. The country had become a hotbed of radical protest, even more so after the Berlin Wall divided it. The generations of artists who either lived through the war as children or adults, as with most SGA contributors, or else were born into its aftermath, were at the vanguard of the push forward.

In Düsseldorf and elsewhere, experimental musicians were breaking the mould just as SGA artists were doing visually and conceptually. The first version of Kraftwerk had formed in the city in 1969, before guitarist Michael Rother and drummer Klaus Dinger broke away in 1971 to form the tellingly named Neu! Dinger went on to lead his own breakaway group, La Düsseldorf. In Cologne, Can had joined forces in 1968 to create their sonic collages of freeform avant psych-funk. In West Berlin, Amon Düül II grew out of the city’s commune that also included key figures of the militant and soon to be notorious terrorist cell, the Red Army Faction. In film, a new wave of German auteurs, included Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Werner Herzog and Düsseldorf born Wim Wenders, were each developing their own particular expressions of disaffection.

While one probably shouldn’t overstate any connections in what were generationally polarised times distanced further by geography, it is likely that some or all of those mentioned would at least be aware of the pockets of activity in other art forms. Just as everybody in Edinburgh doing interesting things knew everybody else doing something similar, chances are that was the case in Düsseldorf as well. Either way, as with the SGA 35, all those named had a huge cultural influence on the generations that followed.

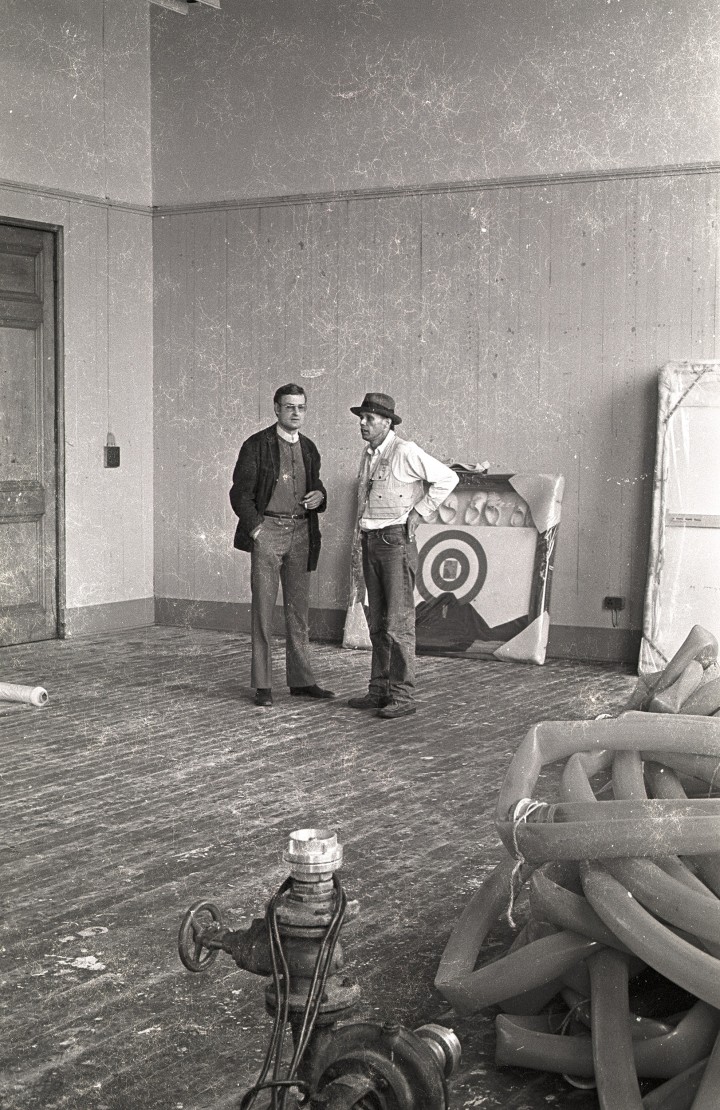

Joseph Beuys and Jürgen Harten in an ECA studio (August 1970). Photo © George Oliver.

Joseph Beuys and Jürgen Harten in an ECA studio (August 1970). Photo © George Oliver.

Long-Term Side Effect

In terms of SGA’s influence, Weikop points to Jon Schueler, the American artist who became friends with Beuys, Rinke and others from the SGA set after seeing Beuys perform Celtic (Kinloch Rannoch) Scottish Symphony at ECA. Schueler lived in the Highland port of Mallaig for several years, and, as outlined by Weikop, his life and work were profoundly affected by his experience of SGA.

Closer to home, a sense of the broader scale of SGA’s reach is captured by Alexander Hamilton’s contribution to Weikop’s book. This comes not just through his role as series editor of the Studies in Photography imprint Strategy Get Arts: 35 Artists Who Broke the Rules is published under. In his short essay, Hamilton brings his first hand experience of SGA to bear, both as a former ECA student, and as a gallery assistant on the exhibition.

The images of the gallery assistants by George Oliver are some of the most striking on show. Their sense of movement, and of people coming together, reveals a participatory experience rather than a passive one. In this sense, SGA was about making connections - between people, art forms and the real life that existed both within and beyond the exhibition. It was a Happening, a social scene made up of misfits and provocateurs. Ultimately, SGA was itself an idea that explored and reflected other ideas – abstract, playful and disarming - about, and of the world.

At this level, the gallery assistants might be recognised in Oliver’s photographs as attempting to carve out a rough-hewn post-war utopia alongside the artists, with their rites of passage pointing the way for an ever evolving landscape where life and art meet. While the day-to-day reality was no doubt much more mundane, as the assistants and artists co-existed, a different form of education to that normally received at that time in institutions such as Edinburgh College of Art emerged.

From this unmediated fusion of art, environment and influence, there followed a sense of self-determination, power and a socially engaged sense of DIY autonomy that a few years later would filter outwards and find its voice through punk and everything that came after. SGA inspired at least one independent record label to be set up. One of the label’s co-founders went on to dress up as Joseph Beuys in a pop video.

Today, SGA’s influence runs on apace, whether those in the thick of things realise it or not. See the assorted new, new waves of conceptual/environmental/performance/community/activist artists (delete where applicable) sired from ECA and elsewhere currently at play. For them, few boundaries exist in terms of crossing disciplines, forms and contexts. It is all part of their own idea of a cultural revolution. And so it goes. The desire to participate remains.

Through its words and images, Strategy: Get Arts – 35 Artists Who Broke the Rules marks a moment when Edinburgh fleetingly opened itself up to the world beyond. Half a century on, the force of nature it hosted resonates still.

Strategy: Get Arts – 35 Artists Who Broke the Rules, Christian Weikop, 2021. Published by Studies in Photography and Edinburgh University Press. £40.