Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

From Townhead to Catterline

By Susan Mansfield, 01.09.2016

In the National Galleries of Scotland store, where members of the public can apply to see works of art which are not on display, one artist is requested more than any other. The person who tops the charts is not Claude Monet, or Vincent Van Gogh, but a 20th-century woman artist whose all-too-short career spanned less than 20 years: Joan Eardley (1921 – 1963).

A major new Eardley show, like the one programmed for Modern Two this winter, won’t be short of visitors, but ‘Joan Eardley: A Sense of Place’ aims to do much more than please the fans. Drawing on a treasure trove of largely unseen material, and bringing in paintings rarely exhibited before, curators hope to shed fresh light on Eardley’s artistic practice.

‘Part of the point is to be looking over her shoulder,’ says Patrick Elliott, senior curator at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art. He describes the business of sifting through drawings and photographs gifted by Eardley’s family, poring over her letters and tracking down people who remembered her as the art historical equivalent of ‘sleuthing’. ‘We’re snooping after her, building up a picture of what she did and how.’

Joan Eardley, Children and Chalked Wall, 1963. Abbot Hall Art Gallery, Kendal © Estate of Joan Eardley. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2016.

Joan Eardley, Children and Chalked Wall, 1963. Abbot Hall Art Gallery, Kendal © Estate of Joan Eardley. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2016.

The show concentrates on the two main ‘places’ of Eardley’s work, Townhead in Glasgow, where she painted children in the slums, and the North-East fishing village of Catterline. Throughout her working life, she moved between the two, and how she drew on both places is crucial to any understanding of work.

‘There’s no way of knowing exactly how she divided her time,’ says Elliott. ‘But you get the strong impression, and it’s backed up by everyone you speak to, that in the early days she’s living in Glasgow and taking trips to Catterline, and at the end it’s the other way round. In a letter to a friend (the artist Margot Sandeman) she says that an artist needs an escape route, you need to get away from what’s familiar. I think Catterline was a safety valve from Glasgow and vice versa.’

Eardley began painting in Townhead shortly after finishing post-diploma studies at Glasgow School of Art in 1948. In the material from her studio gifted to the National Galleries by her family, it is possible to see the extent to which she used photography in her work, capturing images of children and the city environment. ‘She was a very good photographer, her pictures are quite informal, very candid,’ says Elliott. ‘It’s interesting how she uses them in her work, she’s not copying them in a slavish way, there’s always a twist.’

In 1950, when Eardley travelled north to exhibit work at the Gaumont Cinema in Aberdeen, she discovered Catterline. ‘On the face of it, the Glasgow works look utterly different,’ says Elliott. ‘It’s a noisy place, dark and smelly, overcrowded. Catterline was half-empty, many people had left to work on deep-sea trawlers in Stonehaven or Aberdeen. But both are close-knit communities under pressure, which I think she sees so clearly.’

Eardley shunned home comforts in both places: her Townhead studio had no electricity, neither did her favourite cottage at No.1 Catterline, though she joked in her letters that she hung a curtain for extra privacy in the outside toilet. She had other priorities, the primary one of which was to paint. ‘It’s extraordinary that almost all the work we have was produced in 15 years,’ says Elliott. ‘She was absolutely fired up, going hell for leather. At the end, she knew her time wasn’t unlimited, but in a way she always worked like that.’

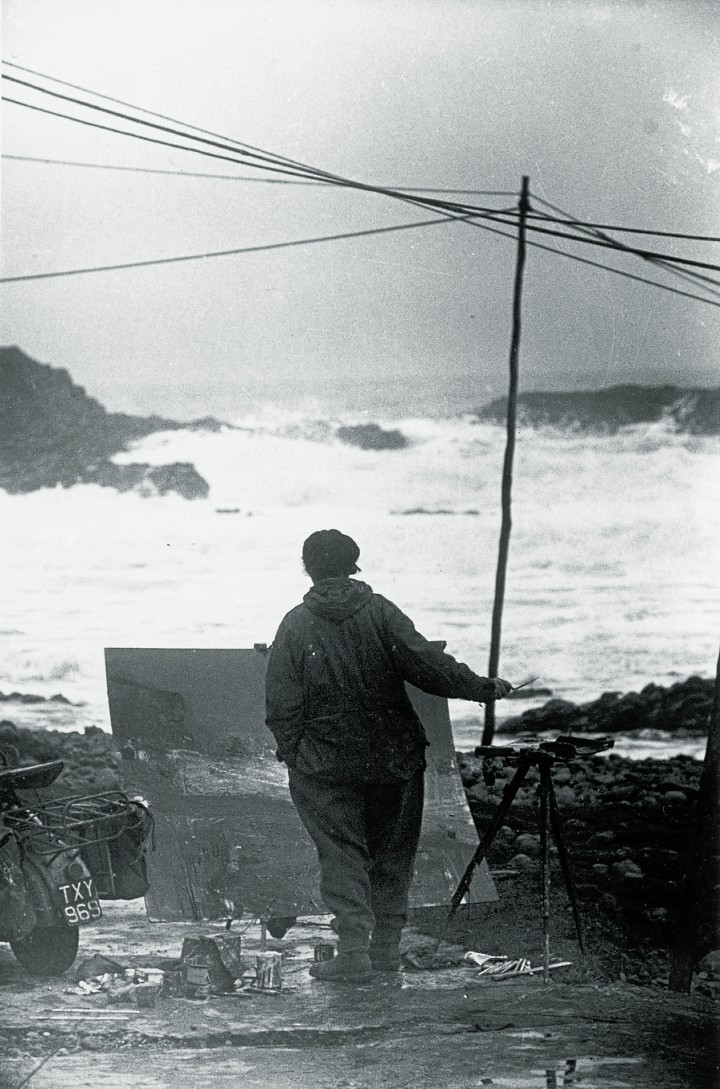

Joan Eardley Painting the Sea at Catterline, 1960 by Audrey Walker. Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art. Ⓒ Jane Walker

Joan Eardley Painting the Sea at Catterline, 1960 by Audrey Walker. Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art. Ⓒ Jane Walker

Her modus operandi varied between her two locations. In Townhead, where her child subjects were unlikely to sit still for long, she used photography and detailed sketches, including evocative gouache and pastel studies. In Catterline, she sketched too, but more ‘as an exercise, almost in the way that dancers or actors get limbered up’. Here, she would work on a dozen paintings at once, waiting for the right light and weather conditions to finish each one.

Unlike Townhead, which was demolished shortly after Eardley’s death, Catterline remains much as it was and it is possible to map - as the curators have done for this show - the exact locations where many major works were painted. ‘They were rarely more than 500m from where she lived,’ says Elliott. ‘A lot of them are literally painted from her doorstep.’

A little ‘sleuthing’ also uncovered the surprising fact that, in her first five years in Catterline, Eardley never painted the ocean. ‘She’s almost continuing something she began in Glasgow which is to paint the buildings, although the sea is just over her shoulder. It was rather amazing and striking that the sea wasn’t something she felt comfortable about, until about 1956 when she starts painting it.’

From then on, however, Eardley didn’t looked back, going on to produce some of her finest works, seascapes which hover on the border of abstraction, and which - she would happily tell admirers - were influenced more by American abstractionist Jackson Pollock than the British traditions of JMW Turner or William McTaggart. These works of experimentation and confidence cemented her reputation among the top British artists of the 20th century, a position she still holds today.

1962. copyright estate of joan ea.jpg) The Wave, 1961 by Joan Eardley. Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Purchased (Gulbenkian UK Trust Fund) 1962. © Estate of Joan Eardley.

The Wave, 1961 by Joan Eardley. Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Purchased (Gulbenkian UK Trust Fund) 1962. © Estate of Joan Eardley.

Susan Mansfield is an arts journalist based in Scotland. This article was published by Scottish Art News in 2016 in response to the National Galleries of Scotland exhibition Joan Eardley: A Sense of Place. The Scottish Gallery of Modern Art (Modern One) will open Joan Eardley & Catterline on the 16th May (closing date tbc).