Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

E. A. Hornel: From Camera to Canvas

By Susan Mansfield, 13.01.2021

In any exhibition of late 19th- and early 20th-century Scottish art, you can always spot the Hornel. That’s the painting in which the subjects, often children, almost disappear into backgrounds of sun-dappled foliage and dancing patterns. It has a prettiness which conceals as much as it reveals. What, we might ask with cynical 21st-century eyes, is it concealing?

This exhibition, the first on Edward Atkinson Hornel for over 35 years, casts fresh light on his practice by exhibiting paintings from the City Art Centre’s collection next to images from Hornel’s own library of some 1700 photographs, held at his former home, Broughton House, in Kirkcudbright. It becomes absolutely clear the extent to which he drew on photography both for the details of his subjects and for overall compositions.

A Kirkcudbright girl in a black dress facing away from the camera, attributed to E. A. Hornel, c.1906–07, glass plate negative, National Trust for Scotland.

A Kirkcudbright girl in a black dress facing away from the camera, attributed to E. A. Hornel, c.1906–07, glass plate negative, National Trust for Scotland.

Seashore Roses, E. A. Hornel, c.1907, oil on canvas, image courtesy of City Art Centre, Museums & Galleries Edinburgh.

Seashore Roses, E. A. Hornel, c.1907, oil on canvas, image courtesy of City Art Centre, Museums & Galleries Edinburgh.

Local girls (his subjects were invariably girls and young women) would attend the Kirkcudbright studio where Hornel would photograph them in the exact poses he wanted for his paintings. They were chaperoned and paid for their time. However, the young model for ‘Sea Blossoms’ - a sun-kissed scene of children smelling flowers on a clifftop - looks a good deal less rosy-cheeked and cherubic awkwardly stretched on his studio floor in her shabby dress.

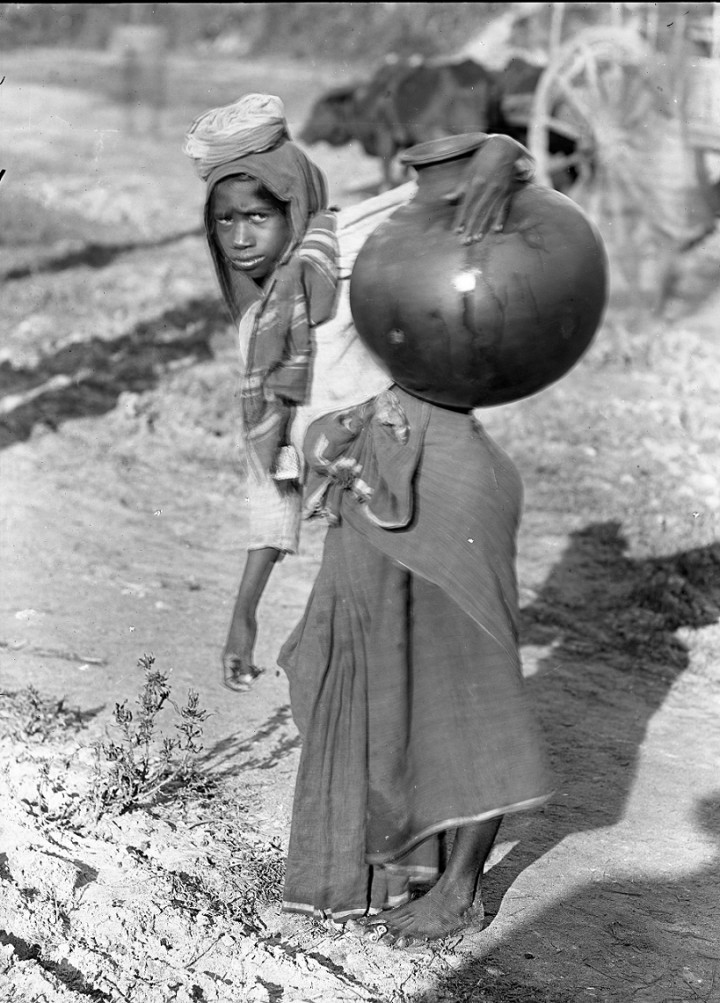

On his travels to Japan, Sri Lanka and Myanmar, Hornel both took his own photographs and collected the hand-coloured images sold to tourists. The show reveals how, in the paintings which followed, the women were made to look more child-like and happier, their tasks less arduous. The titles of the works offer a further clue to what he was doing. In paintings like ‘Burmese Maidens’ and ‘Three Japanese Peasants’, Hornel was looking to capture generic exotica to appeal to the current fascination for these things back home. He did it well, and became very successful.

A girl in Sri Lanka carrying a water jar, attributed to E. A. Hornel, 1907, glass plate negative, National Trust for Scotland.

A girl in Sri Lanka carrying a water jar, attributed to E. A. Hornel, 1907, glass plate negative, National Trust for Scotland.

Ceylon Water Pots, E. A. Hornel, 1907–09, oil on canvas, National Trust for Scotland.

Ceylon Water Pots, E. A. Hornel, 1907–09, oil on canvas, National Trust for Scotland.

Plenty of artists used photography as source material and still do. This new perspective on Hornel does not diminish his skills as a painter, particularly the way he evoked light and mood. He wasn’t concerned with portraying social realism, or with questioning the power dynamics of his time, and perhaps it isn’t fair to suggest that he should have been.

However, what is most interesting is the way this exhibition reveals to us Hornel’s gaze, its unthinking, patrician, Victorian quality, power taken for granted which was so easily abused by the rich white men of his generation. And now, for the first time, we see the answering gaze in the eyes of his photographed subjects, before they were turned into idealised versions of themselves: anxious, resigned, even, in a few cases, silently defiant.

City Art Centre, until 14 March 2021. Free but pre-booking essential. Currently closed due to government regulations. For a virtual taster of the exhibition visit Art UK's Curation here.