Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

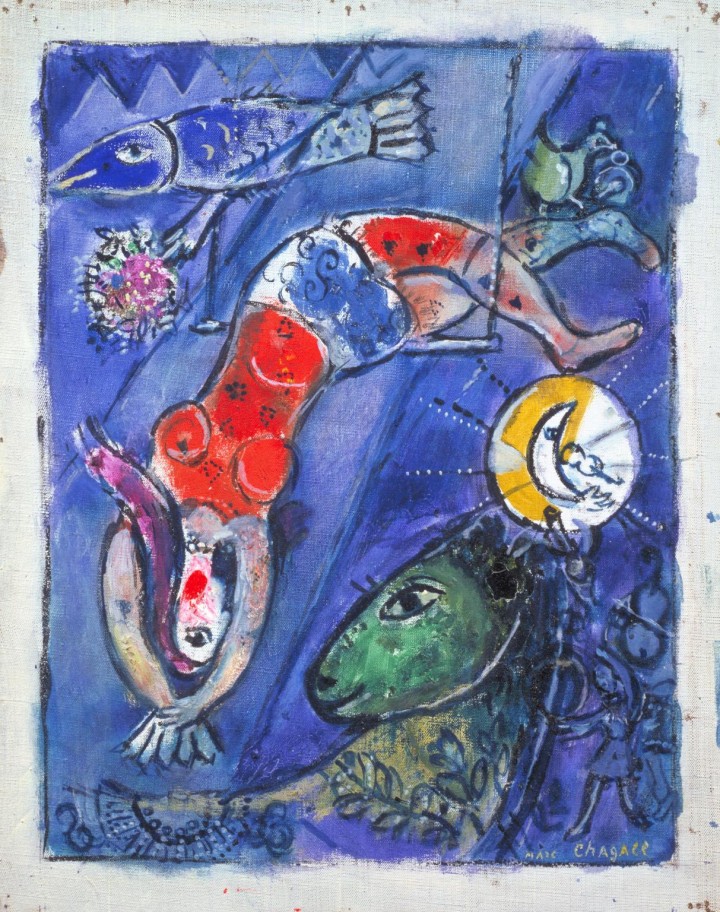

Chagall at the Circus

By Greg Thomas, 25.01.2021

“I would like to go up to that bareback rider who has just reappeared, smiling; her dress, a bouquet of flowers. I would circle her with my flowered and unflowered years. On my knees, I would tell her wishes and dreams, not of this world. I would run after her to ask her how to live, how to escape from myself, from the world, whom to run to, where to go.” This statement, from an essay accompanying Marc Chagall’s 1967 lithograph series Le Cirque, traces a restlessly circling theme in his work with his characteristic combination of emotional intimacy and intellectual recalcitrance.

The circus, and the female horse-rider in particular, appear in works spanning seven decades: from early primitivist pieces like Fair at the Village (1908), which conjures memories of the travelling performers and equestrians who would visit the Jewish Moishe Shagal’s childhood city of Vitebsk, Belarus, to the Gallicised Marc Chagall’s late Old Testament illustrations. “Jacob’s Dream is a circus,” asserts Chagall’s biographer Jackie Wullschläger, perhaps alluding to the acrobatic angels who circle the Jewish patriarch in one of the artist’s 1960s takes on Jacob’s vision of a ladder ascending to heaven.

In-between there are joyful images documenting the artist’s happiest years, in 1920s Paris – like The Circus Rider (1927), one of many inspired by trips to the Cirque D’Hiver with dealer Ambroise Vollard – and others composed in recovery from war, migration, and the traumatic breakup of Chagall’s second significant relationship, with the diplomat’s daughter Virginia Haggard. In Clowns at Night (1957) the circus motifs take on the decidedly gloomy cast of the Beckettian absurd. But the piece acquired by Scotland’s National Galleries is amongst a cluster produced earlier in the 1950s, characterised by the deep, aquatic gouache tones also found in The Blue Circus (1950).

It is a cliché to say that the circus evokes a mood at once comic and tragic. Perhaps more accurately, it is one of simultaneous escape from, and immersion in, real life. Like Chagall’s floating lovers, his animal-human hybrids, the imagery of the circus bears a fantastical naivety that seems somehow vulnerable to the incursion of the adult world: a world in which Chagall witnessed two global wars and narrowly escaped genocide. At the same time, trauma is processed through comic performance: of daring, escape, conflict, humiliation, triumph. Like Samuel Beckett, Chagall also loved the circus-borne slapstick of silent cinema. Whereas Beckett cast Buster Keaton in Film (1965), Chagall professed his admiration for Charlie Chaplin. “Chaplin seeks to do in film what I am trying to do in my paintings”, he declared in 1927. Wullschläger suggests that the artist saw Chaplin as “a sort of secular equivalent of the holy fool of Hasidism.”

Marc Chagall, the Blue Circus, 1950. © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2020.

Marc Chagall, the Blue Circus, 1950. © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2020.

The holy fool – the clown – was in turn a metaphor for the artist, a persona that Chagall cultivated particularly on his return to France in 1948, having fled to North America from Vichy territory in 1941. During the period in which he created L’Écuyère, Chagall enjoyed “play[ing] up the persona of the peasant mystic, at odds with French rationalism” (Wullschläger again). According his friend, the writer Jean Cassou, he “affected to understand nothing which could be reduced to comprehension and played the role of Ivan, the village idiot.”

If Chagall was the fool or Pierrot of the ring – a figure swallowed up here by the flank of the horse, like an infant in the womb – the female rider on horseback takes on the qualities of a saviour, beautiful, upright, brave, leading her steed onwards. Averse to promiscuity, Chagall’s romantic life consisted of a series of faithful, long-term attachments – albeit often characterised by controlling behaviour on one side or the other – and his partners’ qualities found their way into his work. The press release accompanying this acquisition notes that “[t]he dark hair and pale features of this particular horse rider recall those of Chagall’s second wife, Valentina (Vava) Brodsky,” introduced to him by his daughter Ida on the very day Virginia left. It may be that the lengthy composition timeframe reflects the rejuvenating effect of Vava’s appearance on Chagall’s work. Several compositions left dormant were completed shortly after her arrival at his home on the Côte d'Azur.

Other circumstantial influences might include the presence, just down the road from the house in Vence where Chagall settled in 1950, of Matisse’s Rosary Chapel, with its deep blue and yellow stained-glass panels. The nervy, less famous artist had observed its construction from 1949-51 with a mixture of jealous apprehension and wonder. Although he was also near neighbours with Picasso, the presence of a coterie of super-famous artists on the Riviera never sat entirely comfortably with the chronically envious Chagall.

This painting found its way into a public collection from the Edinburgh-based grandchildren of a collector for the Swiss Galerie Rosengart, who purchased it in 1954. It is a striking work, evoking all that is most lovely and mysterious about the oeuvre of a great twentieth-century artist.