Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

Border Crossings: Dundee’s McManus Showcases Ten Scottish Masters of 20th-Century Art

13.11.2025

By Beth Williamson.

This year-long exhibition at the McManus celebrates the work of ten Scottish artists in their collection. All chosen for their inclination to travel beyond Scotland, returning intermittently or sometimes permanently, these artists formed a loose network for whom international developments were equally as important as their roots.

‘The Scottishness of Scottish art’, as Professor Murdo Macdonald has explained, requires an appreciation of different strands of influence that facilitate diversity within unity. A national identity in art is not about uniformity but rather about cultural diversity. The artists in this exhibition embody that sentiment, eschewing stereotypes and culturally inward ideas. Instead, they looked outward and opened up new ideas. Art teaching, for the most part at the Central School of Arts and Crafts (Central School) in London, was another common thread with Basic Design, a radical new form of artistic training, a feature during their time as artist-teachers.

William Johnstone, 'Ode to the North Wind' (c. 1928-30). © The Artist’s Estate of William Johnstone.

William Johnstone, 'Ode to the North Wind' (c. 1928-30). © The Artist’s Estate of William Johnstone.

William Johnstone's ‘Ode to the North Wind’ (c. 1928-30) is a landscape of the mind. It does not illustrate a particular time or place and yet it references his anti-war paintings such as A Point in Time (1929/37). It is in such fluid, amorphous and reworked paintings made in the inter-war years that Johnstone explores the time between the First and Second World Wars, something he experienced acutely. Johnstone's travels in Europe and America reinvigorated his sense of place while an unconventional understanding of time saw him pull the past into the present while simultaneously looking to the future. This is something he explored in his reading, especially J.W. Dunne and his book An Experiment in Time (1927) concerned, in part, with the idea of pre-cognitive dreams. These were ideas he shared with staff and students while Principal at Camberwell School of Arts and Crafts (1938–46) and the Central School (1947–60) where he also introduced Basic Design.

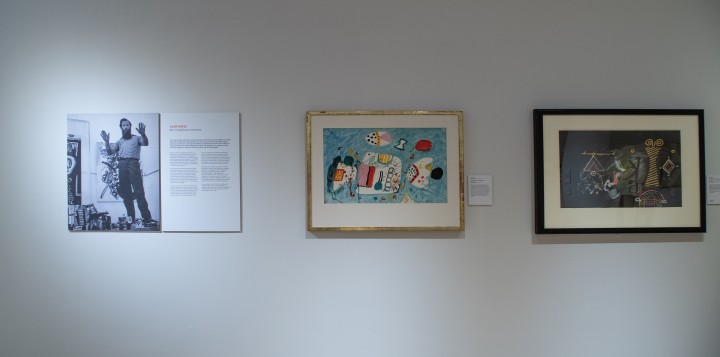

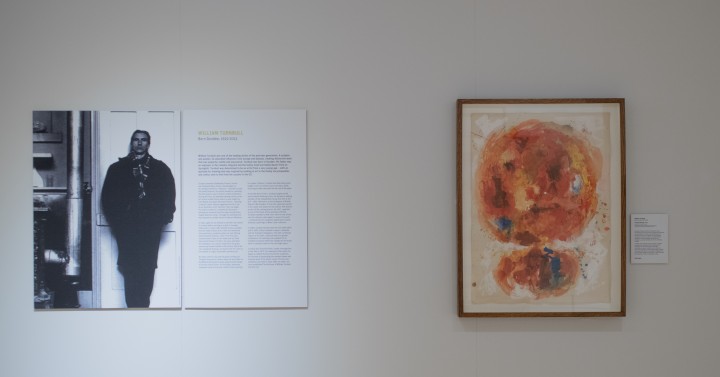

Border Crossing exhibition. William Turnbull, ‘Untitled (Head)’ (1955) © The Artist’s Estate.

Border Crossing exhibition. William Turnbull, ‘Untitled (Head)’ (1955) © The Artist’s Estate.

William Turnbull's ‘Untitled (Head)’ (c. 1955) is one of many heads Turnbull made while working at the Central School (1952–61) where he taught Basic Design. He had spent time in Paris in the 1940s and contributed to the exhibition Growth and Form (1951) at the Institute of Contemporary Arts designing the associated poster, another head. The exhibition was inspired by Richard Hamilton's reading of D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson's On Growth and Form (1917), republished in 1942. With early training through evening classes and work as an illustrator at D.C. Thompson in Dundee, Turnbull soon became a significant figure in post-war British art and education, including exhibiting in New Aspects of British Sculpture in the 1952 Venice Biennale when the 'geometry of fear' captured the post-war mood.

‘mr peanuts (c. 1971). © the artist’s estate..jpg) Eduardo Paolozzi (1924 – 2005) ‘Mr Peanuts (c. 1971). © The Artist’s Estate.

Eduardo Paolozzi (1924 – 2005) ‘Mr Peanuts (c. 1971). © The Artist’s Estate.

When Johnstone appointed Eduardo Paolozzi to teach Textile Design at the Central School (1949–55) the Austrian art theorist Anton Ehrenzweig was already employed there as a dye technician and screen printer. Photographer Nigel Henderson (1951–4) and architects Alison and Peter Smithson (1951–3) were also employed there. Ehrenzweig had previously worked at Donald Brothers in Dundee as a colour mixed and worked closely with Paolozzi to teach him silk-screen printing. Typical of their collaborations was the printed ceiling paper installed in the office of Ove Arup and Partners in London in 1952 while other works were printed then cut up and collaged. In later works such as ‘Mr Peanuts’ (c. 1971) the origins of Paolozzi's earlier print making and collage remains, while augment by a degree playfulness akin to that found in the art of children, something that also interested Ehrenzweig and Johnstone.

Anna Robertson, Fine and Applied Art Manager at McManus Galleries, with ‘The Man That Lived in an Egg’ (c. 1963) by Alan Davie (1920-2014). © The Artist’s Estate.

Anna Robertson, Fine and Applied Art Manager at McManus Galleries, with ‘The Man That Lived in an Egg’ (c. 1963) by Alan Davie (1920-2014). © The Artist’s Estate.

It was while Alan Davie taught in the Jewellery Department at the Central School (1953–6) that he first became interested in African and Pacific Art. As an artist and a jazz musician, he was deeply committed to intuitive and improvisatory modes of working. This kind of intuitive approach was akin to Johnstone's own way of working. Davie adopted a Jungian view of the unconscious at that time, something that is evident in the architypes included in works such as ‘The Man That Lived in an Egg’ (c. 1963). It was Johnstone's close friend Charles Robert Aldrich, who he met in America in the 1920s, who published on Jung's ideas in his book The Primitive Mind and Modern Civilization (1931).

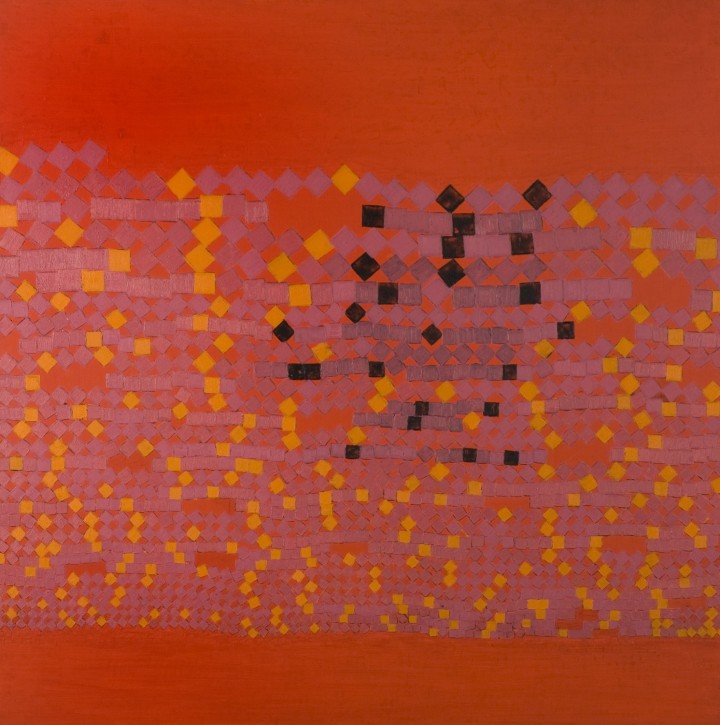

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham, 'Orange, Black and Lilac Squares on Vermilion', (c. 1968). © Wilhelmina Barns-Graham Trust.

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham, 'Orange, Black and Lilac Squares on Vermilion', (c. 1968). © Wilhelmina Barns-Graham Trust.

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham is the only one of the five artists selected here who did not teach at the Central School. She did, however, teach briefly at Leeds College of Art in the 1956–7 academic year. There she was employed by Harry Thubron, an important artist-teacher who advanced the teaching of Basic Design. Exploring the basic tenets of space, form and colour through painting, drawing, carving, modelling and construction was key. Trained at Edinburgh College of Art but by now based in St Ives and, from 1960, between St Ives and St Andrews, Barns-Graham's later works such as ‘Orange, Black and Lilac Squares on Vermilion’ (c. 1968) convey something of the pedagogical principles of Basic Design as she explores the possibilities of geometric shape and colour.

Border Crossings: Ten Scottish Masters of Modern Art is exhibited at McManus, Dundee's Art Gallery and Museum until 14 June 2026