Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

Bodily Traces

By Greg Thomas, 31.01.2023

The title of one photograph in Matthew Arthur Williams’s current show at DCA, ‘The Six Towns,’ put me briefly in mind of Arnold Bennett’s classic of post-Victorian naturalist prose ‘Anna of the Five Towns’ (1902), set in the same collection of industrial villages – known collectively as The Potteries or The Six Towns, amalgamated to create Stoke-on-Trent in 1920 – captured in Williams’s image. It was often said that Bennett ‘forgot’ to include the sixth town, Fenton, when naming his book. In fact, he just liked the flow of the title better with the word “five” in it. The anecdote speaks to the erasures that can be achieved all too easily through authorial or artistic sleight of hand when recording the cultural history of a place.

Speaking to the British Journal of Photography this month, Williams spoke about the other forms of erasure he had encountered when exploring various archives trying to unearth information about his grandparents and cousins’ lives in Stoke, after their relocation from Jamaica around 1960. “Something was amiss,” he stated, recalling the three days he spent looking through photographs of pottery workers in one social anthropologist’s papers before he came across a black face. Between such institutional blind-spots and a popular conception of the industrial Midlands still informed, consciously or not, by a canon of white modernist writers such as Bennett and D.H. Lawrence, it is perhaps unsurprising that Williams’s experience of research towards this show was partly of “things being lost and rewritten or covered up.”

Born in London but now based in Glasgow, Matthew Arthur Williams is amongst a number of Black British artists variously using film, photography, and performance to retrace the cross-Atlantic journeys made by their families during the twentieth century, or more generally to reconcile various senses of ‘home.’ Dancer and film-maker Zinzi Minott’s ‘Fi Dem’ film series, shown at Glasgow’s Transmission Gallery last year as part of her exhibition Bloodsound, echoes Williams’s work in its collage-like splicing of personal and family footage recounting a 1950s emigration from Jamaica with snippets of plummy period newsreel and a soundtrack tending towards musical accompaniment or conversation with the visual element.

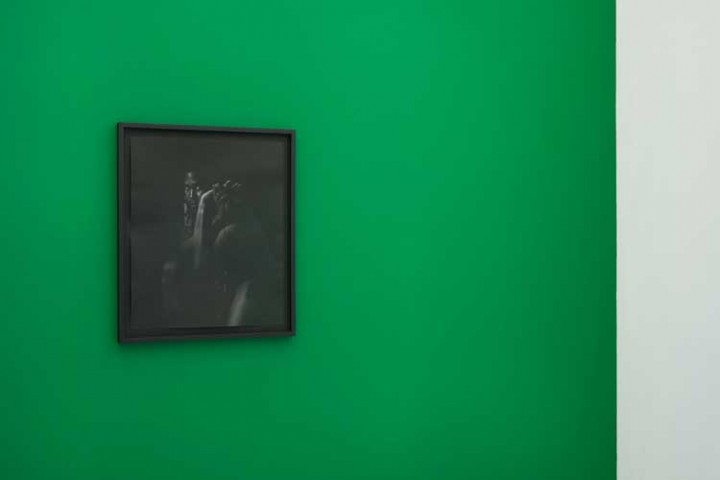

Matthew Arthur Williams: Soon Come. Photo: Ruth Clark.

Matthew Arthur Williams: Soon Come. Photo: Ruth Clark.

What is perhaps most unique about the artist’s approach to his subject-matter – broadly speaking, the Black British diaspora in Britain, which has rightly been the subject of much artistic attention over the last few years – is a certain phenomenological impulse. Whether his photographs are of the semi- urban skyline, a boat, a bank of grass, or a coffin being lowered into the ground, the point of focus often seems to be somewhere in the middle of what is being observed – the stomach or bowels, as it were – as if the camera were shying away from eyelines or panoramas, trying instead to enact a more sensory, tactile encounter. A complementary, fleshy softness to the images is achieved through the use of analogue equipment and darkroom exposure on fibre-based archival paper.

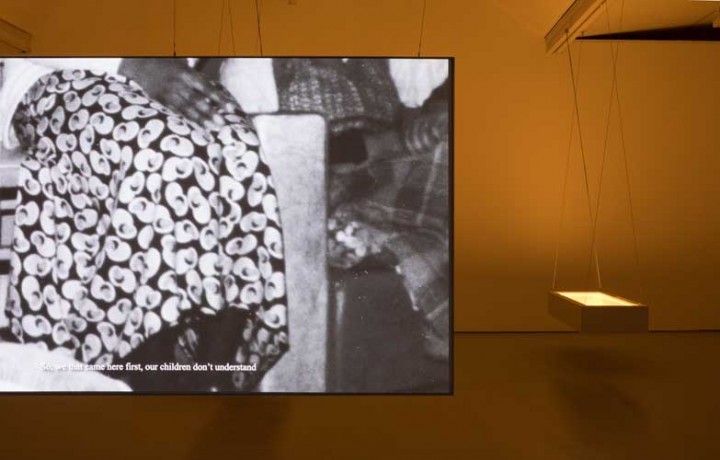

Alongside the shots of chimneys, pot-bellied ovens, and terraced roofs is a 20-minute, twin-channel 4K/16mm film, ‘Soon Come’, which lends the exhibition its name. This work offers itself up with a certain softness, too, through a gauze of smoky Midlands sunset, with a floaty woodwind soundtrack that the exhibition notes nicely describe as “injecting further breath.” Traces of the body seem to be everywhere. On one screen, as the artist explains in an accompanying video-interview, the moving images are sourced from public archives, while the other includes footage recorded by Williams himself, not only in the English Midlands but also in Clarendon, Jamaica, from where his family emigrated. Through the recollections of older relatives we are transported gradually forwards in time, through Williams’s grandfather’s working life in the pits of Staffordshire (he couldn’t find work in the building industry because of the “colour bar”) and the tough but fondly recollected early lives of their children.

Placed between the viewer and the narrative is the figure of the artist himself, always there by implication, but inserted directly at various points. One performed sequence in ‘Soon Come’ shows Williams’s arm embracing another, in a gesture of affection that gradually becomes more like a grapple. Nude self-portraits are placed at the entrance and exit to each gallery: “you enter with me and you leave with me,” to paraphrase William’s video-interview. Like his other subject-matter, the artist is framed with attention to midriff, limbs, and flank as much as face, as if to suggest that what we are seeing has been made with the whole body. This sense of the body as recording instrument, the body as archive, is perhaps what comes across most strongly in this show. Cultural history is presented as focalised through individual memory, thought, and feeling: both as a corrective to the false neutrality of the institutional record and in fond homage to the kind of story it has too often allowed to be discarded.

Soon Come by Matthew Arthur Williams is exhibited at DCA until 26th March.