Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

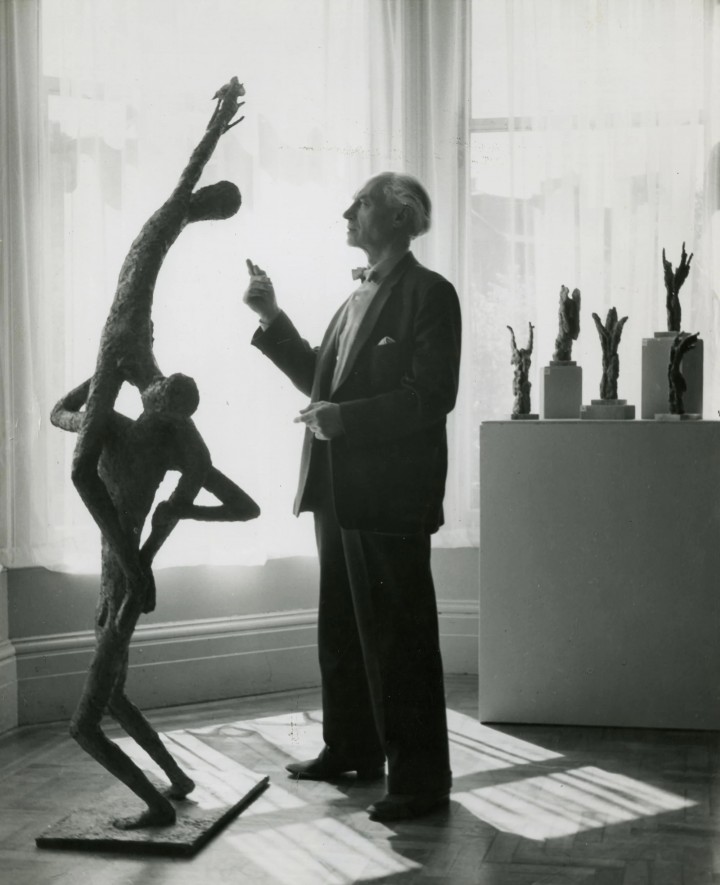

Benno Schotz – Bronze in His Blood

By Neil Cooper, 12.01.2025

When Benno Schotz (1891-1984) visited his brother in Glasgow in 1912, the Estonian sculptor never really left. The then twenty-one year-old returned to his homeland once before settling in Scotland for good. The result of Schotz’s self imposed exile was an artistic and personal journey that saw him become one of twentieth century Scotland’s greatest sculptors.

As a member of the Royal Scottish Academy and Head of Sculpture and Ceramics at Glasgow School of Art, Schotz would also be an inspirational teacher and champion of other artists. At the heart of his work was a network of family and friends, with his wife Milly, daughter Cherna and son Amiel influencing his figurative work prior to him taking a more abstract path inspired by trees in Kelvingrove Park.

Schotz’s migration to Scotland is the drive behind Benno Schotz and A Scots Miscellany, the current exhibition at the Royal Scottish Academy that puts some of Schotz’s key works alongside twelve other first generation migrant artists who made their home in Scotland. Those featured include, from Ireland, Phoebe Anna Traquair (1852-1936), and Fanindra Nath Bose (1888-1926), the first Asian artist to be elected to the RSA. Livng artists in the exhibition include, from Palestine, Leena Nammari (b. 1970), who writes a powerful essay in the exhibition catalogue; and, from America, Ilana Halperin (b.1973). Seen together, this shows off an international diaspora with umbilical links across continents and generations.

Scotland not only made Schotz an artist beyond his engineering diploma from the Royal Technical College and his nine-year stint in the drawing office of shipbuilders John Brown & Company. While he took evening classes in sculpture at Glasgow School of Art during that period, Schotz also drew inspiration from closer to home.

“When he met his wife to be, Milly, in Scotland, she became his soulmate and his fiercest critic at the same time,” explains the exhibition’s curator and RSA’s Head of Collections, Sandy Wood. “He bounced all his ideas off her, and if she didn't think it was worth it, then he tended to listen to what she said.

“I think Benno saw his family as being entwined with his work. Then when his children came along, it was a natural progression that his family would become his muses. This was particularly the case with Cherna, who he modelled from when she was two days old, and at different points throughout her life, until just a few years before he died.

Becoming a full time sculptor in 1923, Schotz and his family lived on West Campbell Street and later Kirklee Road in Kelvinside. Elected to the RSA in 1937, Schotz immersed himself into Glasgow’s lively cultural life.

Benno Schotz, Sir William MacTaggart PPRSA 1970 RSA

Benno Schotz, Sir William MacTaggart PPRSA 1970 RSA

“Schotz was a very social character,” says Wood. “His house was a meeting point for like minded people, artists, friends and students. It was very convivial, and he got to know a great number of artists. There’s a social aspect that comes with being a sculptor in a similar way to being a printmaker, which is perhaps slightly different from being a painter, in that you're often working with other people to realise your ideas. In Benno’s practice as well, the social aspect of modelling and conversation was intrinsic to his busts and to his sculpting from the portrait perspective. It was through that conversation with his models that he brought out what he described as the inner soul, that part of a person that effectively gave his sculptures a feeling of life.”

Schotz’s entire artistic practice was rooted in a holistic, instinctive approach that put his subjects at its centre.

“He wasn't actually looking at what he was doing with the clay,” says Wood of Schotz’s sculptural process. “His hands were so connected to the material and to what he was working with that he didn’t need to look at what he was doing. That meant that he could engage with the person and get them to relax, and get them to be themselves, so they all look absolutely natural.

Of the many artists he supported, Schotz was key to the election of the RSA’s first female Academician, Phyllis Bone. The pinnacle of public recognition came in 1963, when he was appointed the Queen’s Sculptor in Ordinary for Scotland. All this is documented in Schotz’s now hard to find memoir, 'Bronze in my Blood' (1981).

“In his book, he proclaims himself as the first modern Scottish sculptor,” says Wood. “He was a very modest man, but he was also very proud of his abilities. In being recognised as Queen’s Sculptor in Ordinary for Scotland, he was one of the first sculptors not to be Scottish, and to be an immigrant, since the office was made permanent in 1921.

Benno Schotz and A Scots Miscellany installation view, courtesy of the RSA

Benno Schotz and A Scots Miscellany installation view, courtesy of the RSA

“I think that in terms of bringing sculpture in Scotland from a more traditional realm into something more modern, a huge amount of credit should go to Schotz. There were others who also worked in a modern way, but the way that Schotz’s sculpture moved from traditional portraiture into a more abstract approach really formed a marker for the evolution of sculpture in Scotland in the twentieth century. I think certain things would certainly have happened with other artists - you can never credit one artist as being the only reason - but if it wasn't for Schotz, I think sculpture in Scotland would have been very different.”

Benno Schotz and A Scots Miscellany, Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh until 19th January 2025