Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

At the Threshold

By Greg Thomas, 16.04.2021

Confined to our domestic spaces, we are perhaps all a little more attuned to the solitary routine and worldview of Ian Hamilton Finlay, who famously remained within the grounds of his garden at Little Sparta for four decades. This is certainly the case for Alastair Noble, a text and environmental artist who currently splits his time between his native Scotland and the Catskills in upstate New York.

Noble’s practice has for the last few decades converged again and again on a concern with the relationship between reality and its symbolic interpretation, and in particular the transposition of phonetic language into visual signs and vice versa. His text-based sculptures and installations include giant diagrammatic renderings of books placed at thematically resonant locations, such as his Mayakovsky (2003) at Brooklyn Bridge, and illuminated three-dimensional visual translations of Marinetti’s sound poem Zang Tumb Tumb (1912) for a series of installations at Arizona State University and elsewhere during 2004-07.

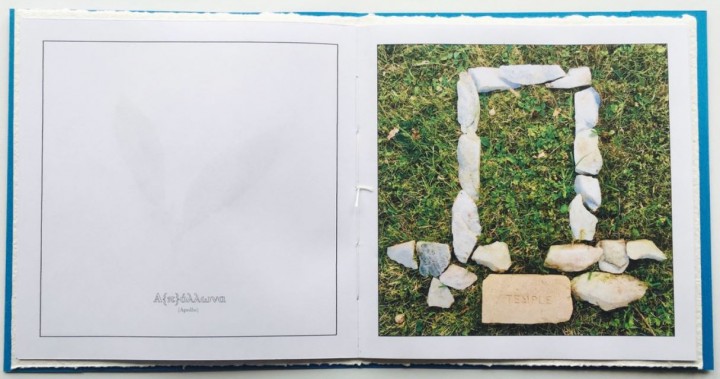

For any contemporary artist exploring the intersection of text and image, Ian Hamilton Finlay’s legacy of course looms large—and when Noble found a brick embossed with the word “Temple” buried in his back garden, it seemed a sign from the gods to gather together the threads of Finlayan and Neoclassical influence on his work. Shortly after this discovery, Noble visited Little Sparta for the second time in twenty years, and on his return to the US created a small shrine in his garden referencing the Portara, the huge lintel which stands as the final remnant of Apollo’s temple at Naxos, beckoning the eye through to the coastline beyond. White marble fragments were repurposed from an earlier, textual earthwork project of Noble’s referencing Wittgenstein to create the miniature sculpture—suitably enough, given the theme of linguistically enmeshed reality that unfolds across the booklet.

Alastair Noble, In Memoriam, 2021. 12 pages, inkjet printed on archival paper 100 gsm, 205 x210mm. Courtesy the artist.

Alastair Noble, In Memoriam, 2021. 12 pages, inkjet printed on archival paper 100 gsm, 205 x210mm. Courtesy the artist.

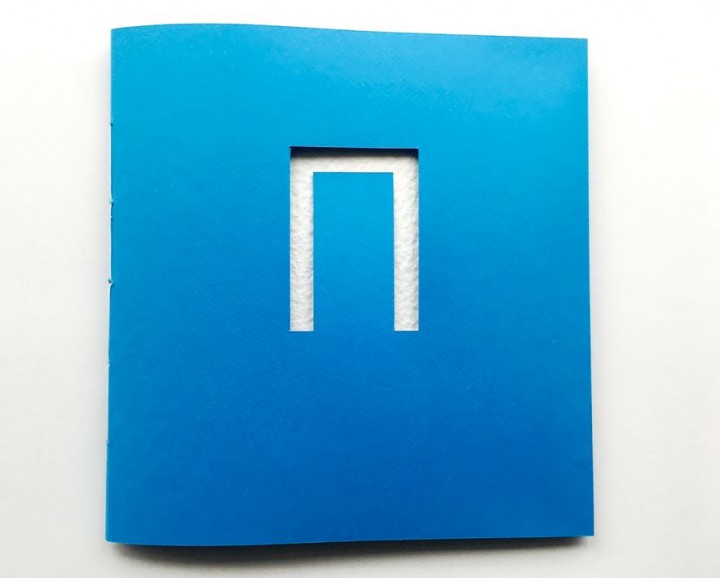

Noble’s central conceit involves a visual echo between the giant marble doorway at Naxos – eerily framing the vast blue blank of sea and sky, alluded to by the booklet’s bright azure cover – and the letter Π (Pi), the first symbol in the Greek transliteration of Portara, Πορτάρα. Emphasised by curly brackets – themselves subtly reminiscent of Apollo’s bow – this motif stamps its presence across the text, and is also cut away from the cover to reveal a marble-like layer of textured white paper beneath.

Around this edifice, whose connotations linger at the doorway between sheer materiality and semantic symbolism, Noble has strewn an array of graphic and textual offerings, including visual poems, photographed sprigs of laurel leaf, and of course an image of the mini-shrine in the Catskills which prompted the project. Heraclitean fragments are also scattered throughout, the most arresting of which, “we exist and we do not exist,” plays off the diametric connotations of the Greek term βίος (life), which, differently accented becomes βιός (bow), the bringer of death—as referenced in another maxim of Heraclitus’s cited earlier in the booklet.

In the spirit of Finlay’s kinetic booklet poems, Noble’s little pamphlet enfolds linguistic, visual, sonic and sensory symbolism to create a mini gesamtkunstwerk. However, the central themes he evokes – the capacity of language to enclose and transubstantiate reality, while at the same time containing fathomless depths of contradiction and incoherence – reveal a concern with the limits and blanks of linguistic sense that deviates from Finlay’s Jacobin moral absolutism, and is testament to Noble’s own, unique vision.

More of Alastair Noble’s work can be found at Arnoble. For sales visit Gnobilis Press.