Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

Artist Interview: Ilana Halperin

By Crystal Bennes, 20.05.2020

llana Halperin’s work explores deep time, the relationship between the slow time of the Earth, connecting geology and the cyclical existence of our daily lives. In February this year Scottish Art News caught up with her as she prepared for two important solo exhibitions at Patricia Fleming Gallery and Mount Stuart. Interviewed by Crystal Bennes.

Q. You’re known for your autobiographical engagement with geology – how did that emerge?

I’d say there are two strands that intersect in terms of my thinking about geology. One is what I call ‘physical geology’ which is materials-based and responds in a corporeal way, trying to make objects using geological or deep-time processes. The other is a more autobiographical way of thinking which revolves around the idea of ‘geological intimacy’. This is where my personal life encounters and overlaps with geologic events in a very particular way. It wasn’t a decision so much as something that happened very naturally.

The first project I did using an autobiographical framework for trying to understand geological time was Nomadic Landmass. When I was about to turn 30, all I wanted to do for my birthday was to visit the Eldfell volcano [in Iceland], formed in 1973, the same year I was born. It was an intuitive desire to visit and from that grew a deep project thinking about family and mortality, as my father was ill and later died, and what it means to grow your family in a geological context.

Ilana Halperin, Sakurajima (October 31st, 2019) I, 2019. Courtesy of the artist and Patricia Fleming, Glasgow.

Ilana Halperin, Sakurajima (October 31st, 2019) I, 2019. Courtesy of the artist and Patricia Fleming, Glasgow.

Q. A truism one often hears is the impossibility of humans being able to comprehend the timescales of geological processes. Given that you work with a field that hinges on these expansive timescales, I wanted to ask your thoughts on this.

It’s tricky because claims about the impossibility of comprehending these things can also become a way of disengaging from challenging ways of thinking about these questions. For me, that’s become a motivating force: what or where are the moments when I can start to feel something in an emotional way that helps me connect to time or place in a more sustained and meaningful way?

Q. Does that contribute to your interest in folding in these personal narratives?

Absolutely. Because I can only really speak for myself, I only know how to make sense of things through personal experience. And different personal experiences have helped me to connect to unexpected ways of thinking about the intersection between a personal, daily sense of time and a geologic sense of time. I also find through being honest about my own experiences and opening up different ways of relating to geological time or our place as human organisms within this very long line of organisms, it allows other people to talk openly about their own experiences as well.

Ilana Halperin, Excerpts from the Library, 2016. Courtesy of the artist and Patricia Fleming, Glasgow 2020.

Ilana Halperin, Excerpts from the Library, 2016. Courtesy of the artist and Patricia Fleming, Glasgow 2020.

Q. You have been working towards two exhibitions, one at Mount Stuart and another at Patricia Fleming Gallery – do they constitute one body of work split across two locations or two distinct shows?

They’re sister exhibitions with interconnected stories, content and materials, but certain questions are teased out more in one or the other. The exhibition at Mount Stuart [on the Isle of Bute] includes four strands of work, actually five, because there’s one performative element. Each of the strands corresponds either to different geological phenomena inside or outside the house or to the geologic context of the island as a whole. One strand is connected to my personal experience of living on the island. Then there’s the geological context of the house, the material reality of the house and all the different immigrant materials it’s composed of.

There are also works connected to certain phenomena in the grounds of the house – for example, a boathouse inside which many stalactites have grown because of an overly lime-rich plaster. After I first visited the boathouse, I tucked it away and later started thinking about it in relation to a former brickworks in Kilchattan Bay near where I live. It produced terracotta roof tiles, drains and bricks and today you often find remnants washed up on the beach. I started collecting eroded bricks and bits of drain three years ago when we first moved to Bute without any set idea of what to do with them. These bricks, along with some historical drains from Mount Stuart, form the basis for one strand.

Q. Will you then send these to the Fontaines Petrifiantes in France to make further artworks – to form slowly from the mineral water and calcium carbonate in the caves – as per previous projects such as Physical Geology?

Yes, I’m thinking particularly about the relationship between local industrial processes, natural geological process and how these interact. I’m also thinking in an anthropocene context, in terms of new geologic categories and evocative objects that mirror the deep-time Earth processes we are situated in.

Ilana Halperin, Textile. Image Courtesy of the Artist and Patricia Fleming, Glasgow.

Ilana Halperin, Textile. Image Courtesy of the Artist and Patricia Fleming, Glasgow.

Q. You’re working on textile pieces as well.

It’s been very exciting for me as I’ve never worked on textiles before. From the 1960s to 80s, my mother was a textile designer specialising in knitwear and I have a number of samples of her textiles which are gorgeous. When I moved to Bute, I started making watercolours after returning from walks. I realised that my palette was almost the same as that of my mother’s textiles, a correlation with Bute’s landscapes. Then Mount Stuart were able to facilitate a collaboration with Bute Fabrics which has been really amazing.

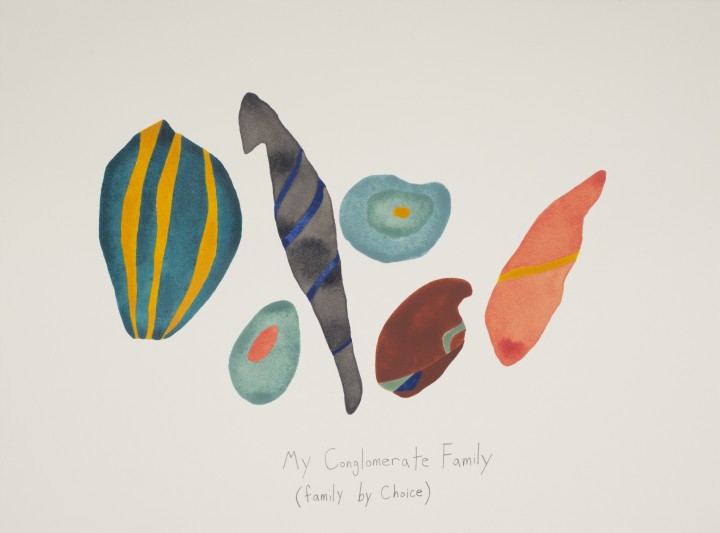

My textile works are also informed by the formation of the island and ideas of international conglomerates. Bute is crossed by the Highland boundary fault line, so Scotland is itself an international conglomerate made of two places that have smashed together. I’m interested in breaking expectations around how we think about the places we’re in.

Ilana Halperin, Excerpts from the Library (detail), 2016. Detail from a selection of an etched ‘book’ of 800 million year old mica. Courtesy of the artist and Patricia Fleming, Glasgow 2020.

Ilana Halperin, Excerpts from the Library (detail), 2016. Detail from a selection of an etched ‘book’ of 800 million year old mica. Courtesy of the artist and Patricia Fleming, Glasgow 2020.

Q. Do the works you’re showing with Patricia Fleming Gallery in Glasgow fall more within the framework of geologic intimacy?

Yes, and there’s a bridge between them that’s linked with mica. One of the major works on Bute is a new series of laser engraved books of mica. My interest in mica stems from being a New Yorker; the city sparkles, and it sparkles because of mica. I started working with mica for the first time in 2012 when I was an artist fellow at National Museums Scotland. I found out that because mica forms in layers, it’s called a book, which was exciting to me because geology is often talked about as a narrative science, but also because geologists often speak of reading landscapes. I also learned mica doesn’t conduct heat. As this was when DCA Print Studio had just gotten their first laser etcher, I talked to them about whether they’d let me try laser etching mica. What’s interesting is that the mica melts and then recrystallises, so the drawings become embedded into each mineral ‘volume’.

The other work I’m developing is connected to reading encountered landscapes, particularly volcanic landscapes. I recently made a field trip to Kagoshima in Japan to make a series of photographs of a volcano there called Sakurajima. One of the interesting things about Kagoshima is that its twin city is Naples because Vesuvius and Sakurajima are very similar, not in terms of eruptive activity but in terms of both looking like a big triangle coming out of water on a bay. In the archives of Mount Stuart, I found a series of travel diaries from the Earl and Marquess during their grand tours when they encountered Vesuvius and Etna. This forms the basis for a performative lecture I’ll be doing at St Blane’s Chapel [currently postponed]. It’s in a volcanic basin overlooking other volcanoes and is on a remarkable site, somehow linking backwards and forwards through time.

Ilana Halperin, Yamaguchi, Japan, Autumn 2019. Photo credit: Alison Stirling

Ilana Halperin, Yamaguchi, Japan, Autumn 2019. Photo credit: Alison Stirling

Crystal Bennes is a visual artist and architecture and design writer based in Edinburgh.

Ilana Halperin’s is an artist originally from New York, now based between Glasgow and the Isle of Bute. Her work has featured in solo exhibitions worldwide including Berliner Medizinhistorisches Museum der Charité, Artists Space in New York and the Manchester Museum. She was the Inaugural Artist Fellow at National Museums Scotland. Ilana Halperin is represented by Patricia Fleming, Glasgow.

Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, ‘Excerpts From the Library’, an exhibition by Patricia Fleming Gallery, is now available to view online.

‘There is a Volcano Behind My House’, Halperin’s major new commission with Mount Stuart Trust on the Isle of Bute has been postponed until 2021. You can follow Mount Stuart’s work on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook.