Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

Always in Paradise

By Greg Thomas, 16.08.2021

'I have very little of Mr. Blake’s company,' the romantic poet’s wife Catherine once remarked. 'He is always in paradise.' Would companions of Frank Walter’s have said the same of him? Just as Blake happily conversed with the denizens of the spirit worlds he invoked, so Walter’s art was rooted in a grandiose cosmology uniting the infinite and the infinitesimal, the material and the supernatural, whose emissaries seemed to populate his waking life.

Here is a diary entry recording a visitation Walter experienced aboard the Tu Ascania, a ship returning him to the Caribbean in near-penal conditions after a failed attempt to enter Britain:

'I can raise the winds, I can disturb the seas and the oceans, I can sink the ship!' I shouted tearing at my hairs, holding my head close to the glass....When I stared through the glass...I could see I imagine a great green Dolphin being ridden by a man dressed in an armour of scaly green material bearing a trident. The figure rose twice to the level of my face looking into the sea through the glass of the porthole, as if it was policing the vessel to safety in the pancake ocean.

Frank Walter, Untitled (Four persimmons). Photograph: Kenneth Milton. Courtesy of the artist’s family and Ingleby, Edinburgh.

Frank Walter, Untitled (Four persimmons). Photograph: Kenneth Milton. Courtesy of the artist’s family and Ingleby, Edinburgh.

This Neptune-like apparition distils a fascination with Greco-Roman mythology – Walter named the small parcel of land he secured in Dominica in the early 1960s Mount Olympus – which reflected his sense of his kingly, white European heritage (sociologist Paget Henry has called the bi-racial artist’s self-image 'a classic case of Fanon’s black skin, white mask'.) But the relative ease with which he welcomed the figure onto the plane of material consciousness is what is of interest here, suggesting a spirit, like Blake, that found ways to experience theophany where others might have seen the symptoms of mental illness.

Like Blake, Walter’s vision of a wider reality was bound by an overarching logic, in his case a Pythagorean model of the universe as a set of concentric, spherical paths. The form of his 'spool' paintings reflects both the visual significance of the circle within this system, and the porthole as an optical frame that shaped many of his most potent memories (as above). Walter spent much of his life on boats, first travelling to the UK, including Scotland, in 1953, to learn about new technologies that could assist his management of a sugar plantation back home—instead, the endemic racism of British society meant that he was forced to take a number of menial jobs.

It is not necessary to understand or concur with the finer details of Walter’s worldview to draw pleasure from the works on display at the Ingleby, which line the four walls of the gallery space at eye level like a dotted golden thread. Indeed, there is such instinctive pleasure to be drawn from their use of colour, abstract formal harmony, and sublimated physical and natural detail that it would almost seem advisable to explore the show first, read the biography second. At the same time, these pieces convey the unmistakable sense of a vast network of esoteric coherences and connections stirring beneath the surface of the visible, a sentiment sharpened by brushing up on some of the basic details of the artist’s life.

Installation view of 'Frank Walter: Music of the Spheres', Ingleby, Edinburgh (July – September 2021). Courtesy of the artist’s family and Ingleby, Edinburgh.

Installation view of 'Frank Walter: Music of the Spheres', Ingleby, Edinburgh (July – September 2021). Courtesy of the artist’s family and Ingleby, Edinburgh.

Immediately on entry, to our left, we encounter a strange, sci-fi self-portrait, a white-suited figure with pale featureless head resting on the rocky surface of an alien planet, while rainbow strips of light shoot across the sky behind. 'Here is Frank Walter...welcoming us to the Fourth Dimension,' Mary-Elisabeth Moore notes in the publication accompanying the exhibition. From there it is a journey through fragments of urban and rural landscape – much of it apparently parsed from memories of foreign travel – to emotion-saturated close-up studies of leaves, flowers and fruit. A second grouping of work consists of minimal seascapes – pink skies and green waves, with deep vibrant undertones, punctuated by the occasional sail or oracle-like chevron of wings – which gradually intermingles with more distinctively Caribbean vignettes, and finally, a set of works depicting animals and people, some of which, as Moore notes, again recall travels abroad—such as the curious twisted visages of a set of Austrian choirboys from a Christmas tour of Europe in the late 1950s. (This cursory walk-through conveys little of that sense, cultivated throughout the show, that what we are seeing rests on the threshold of the intangible.)

In the centre of the room is a set of talismanic little sculptures of birds and aeroplanes. More organic in form on the lower platforms of the display unit, the sharper, more futurist constructions occupy the higher plinths, as if enacting an ascent into cosmic or spiritual space. These pieces give a hint of the range of Walter’s work – as well as being a painter and sculptor he was also a poet and musician – and cap off a thoroughly absorbing journey through the mindscape of a singularly engrossing artist.

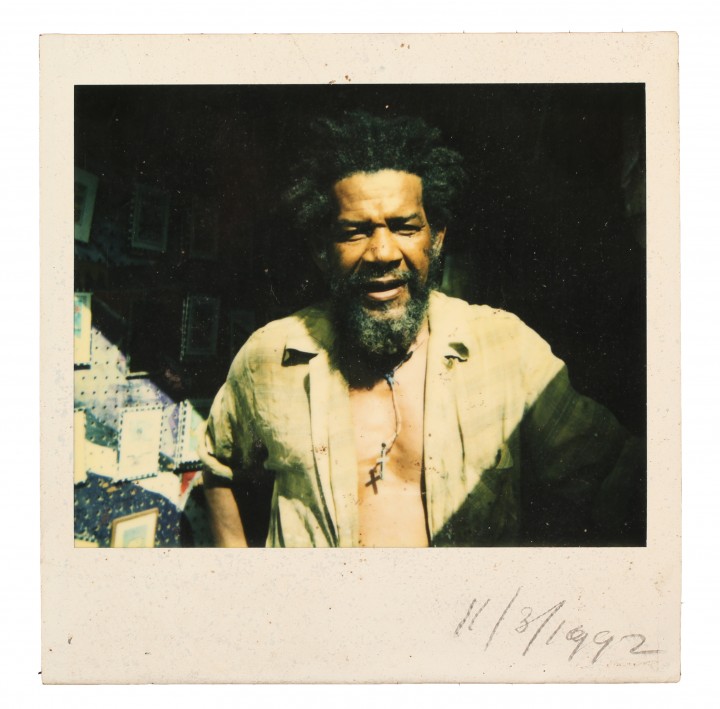

Frank Walter, Polaroid Photograph, 1992. Photograph: Jennifer Merranto. Courtesy of the artist’s family and Ingleby, Edinburgh.

Frank Walter, Polaroid Photograph, 1992. Photograph: Jennifer Merranto. Courtesy of the artist’s family and Ingleby, Edinburgh.

'Frank Walter: Music of the Spheres' is on at Ingleby Gallery, Edinburgh, until 25th September, part of Edinburgh Art Festival