Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

Alexander Nasmyth: A Castle Conundrum

By Theodore Albano, 12.10.2024

Further research may change and redefine one of the key works in the Fleming Collection, ‘A Stormy Highland Scene (View of Culzean Castle Looking onto Arran)’ (c.1810), by famed Scottish landscape painter, Alexander Nasmyth (1758–1840).

Despite being considered one of the earliest and finest painters of the Scottish landscape, Nasmyth (himself a pupil of the great portraitist Allan Ramsay) had never received a compilation or catalogue raisonné of his works until JCB Cooksey’s crucial 1991 publication, Alexander Nasmyth, HRSA, 1758–1840: A Man of the Scottish Renaissance.

In Cooksey’s book, the castle in ‘A Stormy Highland Scene’ has long been identified as the grand bulwark of Culzean Castle, an imposing fortress-turned-estate which looms over the Firth of Clyde in South Ayrshire. In the painting, the Isle of Arran has been brought closer to the forefront, providing a swooping vista of the mountains as a dramatic background.

Culzean Castle holds a fascinating history, including containing an apartment which was gifted for his lifetime to Dwight D Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Forces in Europe in WWII (and later US president), who referred to Culzean as his ‘Scottish White House’.

Nasmyth was commissioned by the Kennedy family in 1815 to undertake a series of images of the castle and its surroundings after a major renovation had been completed headed by architect Robert Adam, along with views of other family properties, amounting to some 15 paintings in total. Nasmyth thus came to know the area intimately. Nasmyth was also a keen architectural designer who fully understood how to depict buildings in a faithful and engaging manner.

The Fleming Collection painting is almost identical to another contemporary 1810 painted composition, also identified as Culzean Castle, held in a private collection, as well as an 1810 sketch held in the National Gallery of Scotland. It is with these three works that the conversation around the castle, and its location, deepens.

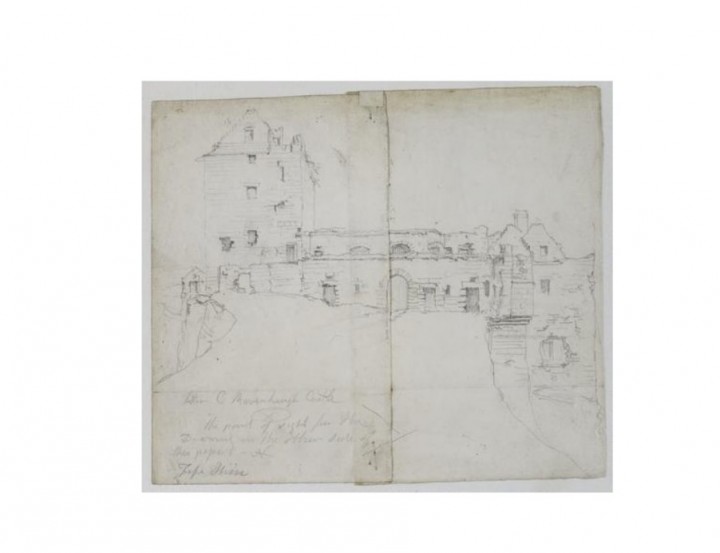

-2.jpg) Alexander Nasmyth, Culzean Castle Looking Across to Arran, c. 1810, image courtesy of the National Gallery of Scotland, graphite on paper.

Alexander Nasmyth, Culzean Castle Looking Across to Arran, c. 1810, image courtesy of the National Gallery of Scotland, graphite on paper.

The 1810 sketch provides the key to the attribution. In this drawing, clearly done on location, the rounded barrel outline of Culzean Castle’s keep can be seen: the landscape setting of the drawing was copied and used for the subsequent paintings. The two paintings from 1810, including ‘A Stormy Highland Scene’, depict a much squarer building with a series of connecting galleried arches, completely lacking the distinctive rounded outline of the real building seen in the sketch.

Archie Kennedy, Earl of Cassillis, and descendant of the Kennedy family who completely rebuilt the castle and commissioned Nasmyth’s other works, says: ‘To me, what really precludes the castle in the painting from being Culzean is that the perimeter wall is so tight to the castle and that there are no courtyards or gardens... By Nasmyth’s time, the barmkin wall was already breached on the landward side by Sir Archibald Kennedy’s 17th century terraces.’

We know Nasmyth completed these two paintings, as well as the sketch, five years before he was commissioned by the Kennedy family to paint the building and surroundings. The question is, why did Nasmyth depict a completely different castle on the site of Culzean? Is it a real castle, or merely an imagined, romantic view?

The argument could be made that the castle is simply a capriccio, an Italian painting term usually used to describe an imaginary topographical scene, sometimes drawn from actual sites and recombined in inventive relationships for decorative effect. It is known that Nasmyth indulged in capriccios, but when it came to real, actual sites, his architectural sensibilities usually won out and real buildings were almost always depicted.

Discussing the painting with Archie Cassillis, the works of some other contemporary artists emerged, including the prints of the 18th and early 19th-century naval officer and architectural enthusiast, John Clerk of Eldin. Clerk spent his later years traveling around Scotland creating scenes of famous castles and other points of geographical interest.

Alexander Nasmyth, Sketch of Ravenscraig Castle, c.1813, graphite on paper, image courtesy of Historic Environment Scotland

Alexander Nasmyth, Sketch of Ravenscraig Castle, c.1813, graphite on paper, image courtesy of Historic Environment Scotland

One of these etchings, of Ravenscraig Castle in Kirkcaldy, bears a striking resemblance to the castle in ‘Stormy Highland Scene.’ From here, further investigation discovered that Nasmyth himself created at least one painting and several drawings of Ravenscraig in 1810–13. His 1813 drawing is even more similar to ‘Stormy Highland Scene’, and convincing enough to possibly be the actual castle in the work. The partner painting to ‘Stormy Highland Scene’ is even more convincing, with the depiction of lower galleried arches nearly identical to the Ravenscraig sketch.

It can be proposed that these two c.1810 works have long been misattributed as Culzean Castle, when in fact they depict a cross-coastally switched Ravenscraig. Nasmyth combines the faithful landscape around Culzean Castle, while swapping the castles. While seemingly a small detail, this switch speaks to Nasmyth’s interest in depicting actual, real places even when he allowed for artistic license of location and environment. While he received commission for the real Culzean Castle years later, he allowed his artistic sensibility to take over in the earlier works.

Alexander Nasmyth’s ‘A Stormy Highland Scene’ is exhibited in Romance to Realities: The Northern Landscape and Shifing Identities at Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle, until 26th April 2025