Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

Alexander Moffat at 80

By Susan Mansfield, 03.05.2024

On New Year’s Day 1963, barely a mile from the Dunfermline gallery which hosted his 80th birthday exhibition, Alexander (Sandy) Moffat painted a portrait of his grandfather. Now Alexander Lawson joins the throng of famous faces Moffat has painted since.

However, grandfather’s portrait excepted, the 80th birthday show at Fire Station Creative is all recent work. Having spent 60 years as a painter, teacher and chronicler of Scotland’s cultural history, Moffat is showing no signs of slowing down. “You suddenly realise there’s all this work to do,” he says mildly, with an almost- laugh. “This show has been good in the sense that it’s allowed me to pull these more recent things together and think about what I might do next.”

Moffat’s “work” has long had a specific purpose in mind. Art historian Bill Hare, in Facing the Nation, his book on Moffat, wrote that he has “an ongoing mission” to record, through portraiture, the cultural and intellectual heritage of modern Scotland. While there are some more personal pictures here - a thoughtful self-portrait, tributes to his friend John Bellany - the majority are what he calls “public paintings”.

“Just to paint for yourself, that’s fine,” he says. “But to do something a little bigger than that would be my ambition. Picasso once said something like a painting is a bridge between the artist and the viewer. I feel, if it’s good enough, it will speak to other people. That’s what I want.”

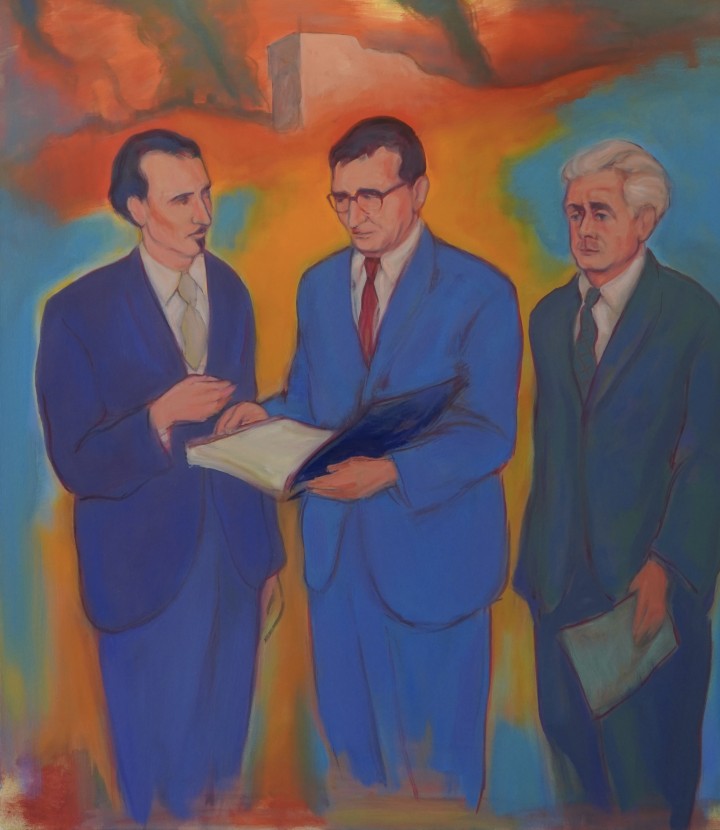

Key works in the Dunfermline show include ‘The Border Guards’, a group portrait of Hugh MacDiarmid, artist William Johnstone and composer Francis George Scott, “the inventors of the Scottish Renaissance in the early 1920s”, and ‘Passacaglia on DSCH’, MacDiarmid and composer Ronald Stevenson meeting Shostakovich at the Edinburgh Festival in 1962. They are paintings which capture, retrospectively, the story of a nation grounded in ideas, reaching out to the wider world.

The Border Guards, Image courtesy of the Artist

The Border Guards, Image courtesy of the Artist

Even as a boy growing up in Cowdenbeath, there was a sense for Moffat of “a big culture out there somewhere”. “I heard my parents talking about the Edinburgh Festival, and the history of Dunfermline itself, being the old capital of Scotland, the Abbey being a centre of learning and music, the ruins of the palace, Robert the Bruce. It all adds up into a sense of something that when you grow up you might join in.”

Then, in 1958, when he was 15, his art teacher took the class to see the Moltzau Collection being exhibited at the Edinburgh Festival. Suddenly, here was modern painting from the Impressionists to the post-war avant- garde; here were Picasso, Cezanne, Matisse. “I never looked back. From that point on it was a question of going to art college.”

From the outset, art college was about more than learning to paint. Moffat and his friends Alan Bold and John Bellany plunged into a broader education in history, philosophy, politics, literature. “We were arguing with ourselves all the time. I think the most important thing was to see beyond painting, to see that there were these other art forms that were equally important and valid, and one could learn from them.”

In 1962, they heard Hugh MacDiarmid read at the Writer’s Conference in the Usher Hall, where he had his much publicised spat with Alexander Trocchi. They also began to seek out the writers and cultural figures who, in those days, frequented the pubs of Rose Street. “I think Alan Bold heard MacDiarmid on the radio and he became interested. Then, once we’d got our teeth into MacDiarmid, we began to discover, there’s a guy called MacCaig, there’s Robert Garioch, there’s a Gaelic poet called Sorley MacLean.

“Edinburgh in my students days and afterwards was a hotbed of artistic and intellectual activity. All sorts of characters would hang out [in Rose Street], lawyers, librarians, jazz musicians, would-be poets. According to the history books, T. S. Eliot visited Milne’s Bar on an early visit to the festival. Dylan Thomas did too, all these people had been there. It had a kind of mythic status.”

Passacaglia on DSCH, image courtesy of the aritst

Passacaglia on DSCH, image courtesy of the aritst

At the same time, both Moffat and Bellany were rejecting the fashionable abstract expressionism of the day and turning to figurative painting, taking a weekly class with Colin Thompson, then director of the National Gallery of Scotland, on the painting techniques of the Old Masters. “I remember John was big on underpainting after that!” he laughs.

“We had been fashionable abstract painters at the beginning, but after that [class] we thought we’ve got to move towards the human figure. It was gradual discovering how we could create a language of figuration which was truly modern. And then, in 1965, John went the RCA in London and there was a huge Beckmann exhibition in the Tate. That was probably a clincher, we thought, ‘We can do this!’”

Painting a portrait of the journalist Neal Ascherson in the mid 1970s, Moffat hit on a way of making a kind of history painting. Ascherson was based in Berlin, and Moffat would go on to paint three ‘Berliners’ paintings, putting the journalist in the frame with key figures from the recent past such as Ulrike Meinhof and Rosa Luxemburg.

He would employ this idea when painting Hugh MacDiarmid, placing him in a Borders landscape surrounded by the writers and thinkers who formed him. And, as well as painting individual portraits of the Rose Street writers, he came up with the idea of a group portrait bringing them all together, ‘Poets’ Pub’. It might be his best known work, and now hangs in National Galleries Scotland: Portrait.

“When I did ‘Poet’s Pub’, they weren’t all that well known in a way, I just thought I’ve got to do this because it’s part of my life as well, it’s a quasi autobiographical painting. I thought they were important and should be recorded in some way. It was only later that people began to want to reproduce it in books, and all those poets were revered.”

Many years later, it was a friend, filmmaker Douglas Eadie, who persuaded him to paint ‘Scotland’s Voices’, an epic group composition celebrating the folk revival of the 1950s with Hamish Henderson at its centre. “He was like a dog with a bone. He wrote me a long letter telling me exactly who should be in the painting, the singers and musicians, and MacDiarmid, Gramsci and Heine. And I thought, ‘I’ve got to do this damn painting!’ It became quite exciting, but it was a struggle as well.”

Scotland's Voices, image courtesy of the artist

Scotland's Voices, image courtesy of the artist

Although ‘Scotland’s Voices’ was first shown in 2017, Moffat is a great reviser of his work and took time to “tweak” it for the Dunfermline show. Now, he says he’s satisfied. “I saw it on the wall in Dunfermline and, for the first time, I thought ‘That looks damn good - I’m proud of that!’”

‘Scotland’s Voices’ lead to a series of works about Hamish Henderson, which lead in turn to a meeting with Henderson’s widow, Kätzel. “And so you get new things coming into your life, even though you’re old and you’re not supposed to meet new people. You keep on meeting people and it keeps on inspiring you.”

Now, he’s planning another major group portrait - “I’m calling it my art school painting” - a group of artists at work in a studio, some of whom will be students he taught in his 25 important years in the painting department at Glasgow School of Art. “It will be a Mackintosh studio, so it’s a homage to the Mackintosh Building as well. But it will have to be big. So that could be my final masterpiece!”

Fire Station Creative Install Shot Photo Ian Moir

Fire Station Creative Install Shot Photo Ian Moir

Alexander Moffat at 80, Fire Station Creative, Carnegie Drive, Dunfermline. Run closed 28th April 2024