Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

A Shared Journey - but a different vocabulary?

By Susan Mansfield, 04.11.2024

It’s quite rare to find a marriage of two artists in which both parties flourish, but the 52-year partnership of Elizabeth Blackadder and John Houston is an exception. A Journey Shared, the exhibition created by the Royal Scottish Academy (RSA) in Edinburgh last summer is a celebration of two long and significant careers, drawing on the considerable holding of artworks left to the RSA on Blackadder’s death in 2021.

Seeing their work side by side presents an opportunity to see how each pursued their own distinctive path, fed by the shared journeys they made all over the world. Between the lines, we see their support of one another’s work, most notably Houston’s support for Blackadder’s independent career from the 1950s onwards, when many women artists still faced significant challenges.

However, when the bodies of work are shown together, some compare and contrast is inevitable. Language used to describe Houston’s practice has meant that a particular vocabulary has evolved to describe Blackadder’s work in relation to it. Houston’s “expressive painterly style” is compared to Blackadder’s “finely observed still lifes and botanical studies”. Painter Alexander Moffat writes that Houston’s paintings have “a grandeur and authority placing him firmly in the larger story of Scottish art,” and does not mention Blackadder.

Anyone with half an inkling of feminist theory will notice that this language is gendered. In his obituary of Blackadder, art critic Charles Darwent went further, describing her work as “old fashioned” and adding that “Blackadder’s watercolour irises might have been painted by an unusually adept aunt”. The picture he paints is of a reserved older woman who liked cats and flowers and would not talk about her work. And this is true, but it’s not the whole story.

Too easily, that becomes the lens through which we view Blackadder’s work, not helped by the ubiquitous images of cats and flowers which were so readily turned into cards and tea towels. Too easily she starts to be dismissed as highly competent but a bit outdated, or to be appreciated rather patronisingly, like Darwent’s sweet old aunt

I remember asking Blackadder, in an interview in the noughties, what work of art in the world she would most like to own. She talked about Uccello’s ‘The Battle of San Romano’ and the 13th-century Italian artist Cimabue as well as modern Italian painters such as Mario Seroni, and others whose work she had seen in the 1950s. My sense was of an artist immersed in art history (which she studied, in an early version of Edinburgh College of Art’s Fine Art degree), who also had an acute awareness of modern developments in painting. If Houston was one of the first Scottish artists to engage with Abstract Expressionism, one must not forget that Blackadder was looking at the pictures alongside him.

A brief consideration of her still lifes reveals rigour and experimentation. For one thing, she did not set up an arrangement of objects and then paint it, she let each object suggest the next in a free association, often picking out colourful things she had acquired while travelling. She said she was as interested in the relationship between objects - the spaces between them - as much as in the objects themselves.

.jpg) Elizabeth Blackadder, Still Life with Fan (1977)

Elizabeth Blackadder, Still Life with Fan (1977)

From early on, she played with perspective: some paintings look from the side, some from above, some both. Often, as in paintings like ‘Still Life With Fan’ (1977), the edges of the table seem almost to disappear leaving objects floating, in Duncan Macmillan’s words, “more an illuminated space than a solid surface”. She experimented with bold fields of colour, in works such as ‘Dark Still Life With Tulips’ (c.1965) and pattern in ‘Portuguese Still Life’ (1966).

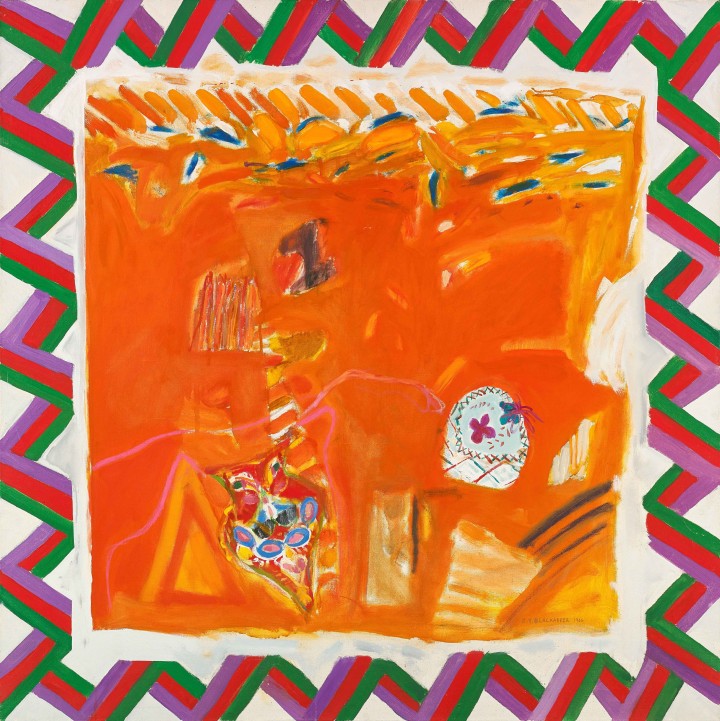

Elizabeth Blackadder, Portuguese Still Life, 1966

Elizabeth Blackadder, Portuguese Still Life, 1966

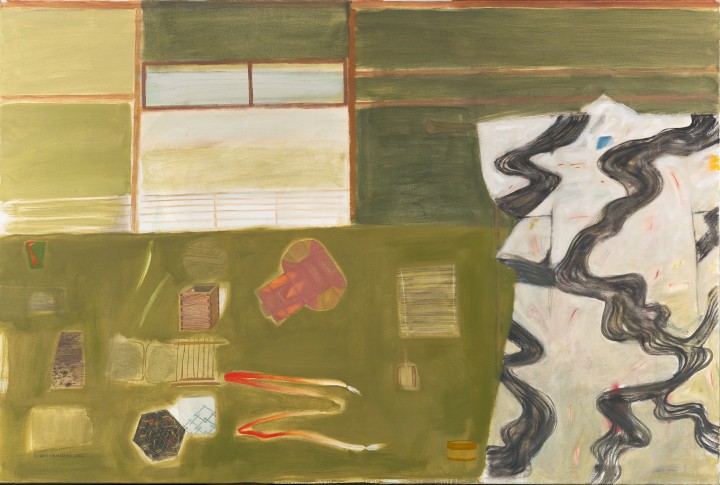

‘In Flowers and Red Table ‘(1969, Fleming Collection) and ‘The Red Bouquet’ (1975), the objects seem almost incidental: let them fall away and you’re left with abstract colour, practically Barnett Newman. Travels to Japan led to more experimentation in works like ‘Still Life with Kimono, Kyoto’ (2002), and this vivid free- flowing painting continued in, for example, ‘Fruit on a Red Table’ (2010).

Meanwhile, Darwent’s description of her flower painting, “not so much meticulous as engineered... botanical painting rather than flower painting” is at odds with how the work was produced. One former student described how she painted flowers, working on a flat surface and letting the paper almost flood with water and pigment. This is painting on the edge of danger: one drop of water too far and the piece is ruined. It is the opposite of the botanical artist’s precision. If the results look precise, it is more likely because of her intuitive ability to express form on paper.

Elizabeth Blackadder, Still Life with Kimono, Kyoto, (2002)

Elizabeth Blackadder, Still Life with Kimono, Kyoto, (2002)

And what of that difficult word “domestic” which has been used down the years to describe the work of women artists (and writers), with its loaded implications of a lesser realm concerned with everyday things, a place of limitations? Yes, Blackadder painted at home, in two studios created for the purpose, one for oils and one for watercolour. She found many of her subjects in her home and garden where she grew her own irises and orchids, and where she and Houston created an ornamental Japanese-style fish pond and tea house inspired by their travels. It was a home which - as homes do - encompassed a whole world.

Once, when I visited, Blackadder was painting a still life which included a butternut squash, one of many squashes, pumpkins and melons which found their way into paintings down the years because she loved their shape and colour. She admitted, a little shamefacedly, that she had never cooked one. By the time the painting was done, the squash was always past its best. Her first priority was always the work.

The RSA now holds a remarkable study resource, not only in its collection of artwork but also the personal archives and contents of the Blackadder and Houston house and studios. I hope that future students of that material will be conscious of the lens through which they might be looking, and be free to see the unexpected. I hope they will not be afraid to do as Blackadder herself wanted and let the work speak for itself.

You can view A Journey Shared online: