Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

The Art Market

By Susan Mansfield, 14.09.2021

.jpg)

There were no murmurs of surprise in the saleroom when a 14th-century gothic ivory casket sold for nearly £1.5million after a dramatic ten minutes of bidding, no ripple of shock across the assembled crowd. There was no sound at all because there was no crowd; the only person in the saleroom was the auctioneer.

The casket broke the record for the highest price ever achieved by an object at auction in Scotland (£1,455,000, including buyers’ premium) at an online sale at Lyon & Turnbull in Edinburgh in May. After a year of online auctions, the record price simply confirmed what managing director Gavin Strang has described as ‘an incredible year for art and antiques’.

When the country went into lockdown in March 2020, Lyon & Turnbull took a decision Strang says felt like ‘a monstrous gamble’. Instead of cancelling the Decorative Arts: Design from 1860 sale they had planned for early April, they decided to go ahead online. The overwhelming success of that sale (which was followed by 28,000 people) gave them the confidence to continue with online sales, and inspired other auction houses to follow suit. After 15 months, they report sell-through rates up by 10 per cent, coupled with ‘the kinds of prices that we haven’t seen for a long time’.

Strang says several things help account for the ‘mini boom’, such as buyers having disposable income they couldn’t spend on luxuries such as travel, and lockdown life inspiring more people to invest in objects for their homes. While pivoting online was a steep learning curve under the strictest lockdown conditions, the company quickly adopted 3D Matterport technology (before lockdown, most widely used by estate agents) to create film and 3D imaging.

Now, this technology is here to stay. ‘We’ve leapt into a digital future and there’s no going back,’ Strang says. ‘In the old days, two or three hundred people came to an auction, now two or three thousand view an object online. Some people will come back to auctions, but I don’t think everyone will. If they trust the technology and trust the brand, they have realised how easy it is to bid on a mobile device wherever you are.’

John Byrne, Me & Him II, 2020, from Byrne's exhibition 'Welcome to My World' at the Fine Art Society in Summer 2020. Works sold between £950 - £20,000. Image courtesy of the Fine Art Society.

John Byrne, Me & Him II, 2020, from Byrne's exhibition 'Welcome to My World' at the Fine Art Society in Summer 2020. Works sold between £950 - £20,000. Image courtesy of the Fine Art Society.

Art dealership the Fine Art Society, based in Edinburgh and London, is also reporting ‘a fantastic year for sales’ despite the pandemic. When it became clear lockdown would not be over quickly, managing director Emily Walsh says she and her team threw themselves into engaging audiences digitally.

‘In Edinburgh, we’ve always had to go out to people, so we are reasonably used to that. I think, due to the fact that people were at home and had expendable income, anything we sent out, whether emails or social media, got immediate responses. And we were able to apply ourselves to the exhibitions instead of being distracted by the day to day life of the gallery.’

She said the amount buyers were prepared to pay for unseen works increased significantly, from a pre-lockdown figure of around £5000 up to £20,000 and even £50,000. ‘As is often the case in extremis, people tend to home in on things they are more familiar with. Our John Byrne show was a great success, and we’re seeing the same pattern with names from the past.’

She says while online marketing will continue, the challenge is to stay focused now the gallery is open again. ‘I’ve noticed a slight distraction with the return to the retail space and the admin that brings. We need to prioritise the picture over everything else, that’s what we were able to do in lockdown.’

Kevin Harman, Synthetic Nature Reserve, 2018, from Harman's exhibition 'Kevin Harman' at Ingleby in Spring 2021. Works sold between £20,000 - £65,000. Image courtesy the Artist and Ingleby, Edinburgh. Photograph: John McKenzie.

Kevin Harman, Synthetic Nature Reserve, 2018, from Harman's exhibition 'Kevin Harman' at Ingleby in Spring 2021. Works sold between £20,000 - £65,000. Image courtesy the Artist and Ingleby, Edinburgh. Photograph: John McKenzie.

When Edinburgh’s Scottish Gallery had to close its doors in March 2020, it was the first period of closure in the gallery’s 179-year history. Managing director Christina Jansen said it was an anxious time, with the Art Newspaper predicting that galleries of their size would find it hardest to survive the pandemic.

‘I decided we had to have a plan,’ she says. ‘I didn’t want to give up on the history and the artists we represent. There was a moment of fear when I thought, “how relevant are we in a pandemic?” But we quickly found out – the feedback was immediate. Art was a release from all the anxiety.’

The gallery team threw themselves into creating online content. A series of films, Great Scots in Isolation, was launched, monthly newsletters became weekly, and they soon realised the potential for virtual studio visits and even virtual private views to engage a wider, more diverse audience. New clients appeared online from North America, Australia and New Zealand, though access to European markets was ‘stuffed by Brexit’.

Jansen says she takes nothing for granted going forward, and believes the economic impact of the pandemic could continue to affect the art market for up to two years. ‘My only thought last year was: “how do we get to 2021?” and we’re very, very grateful to be here. We’ve had great feedback from audiences and artists, but that doesn’t mean we have a formula. We have to continue to be innovative to remain relevant, but we have a better toolkit now.’

Kate Downie, Still from the Scottish Gallery's series 'Great Scots in Isolation', 2020. Image courtesy of the Scottish Gallery. Image: Michael Wolchover.

Kate Downie, Still from the Scottish Gallery's series 'Great Scots in Isolation', 2020. Image courtesy of the Scottish Gallery. Image: Michael Wolchover.

The pandemic meant big changes to the modus operandi of Edinburgh’s Ingleby Gallery, whose focus is usually on engaging with collectors through international art fairs. However, as director Richard Ingleby says, they were perhaps better prepared for the crisis than some of their competitors.

‘The galleries we compete with are mostly in New York, Berlin, Shanghai, London, Paris, places where there is much more footfall. When everybody’s doors closed in March, we felt, for the first time ever, that we were on a level playing field, and we were a bit further forward. We’ve always had to work really hard to engage people at a distance. We were watching some of the bigger galleries floundering around with online engagement and we were just getting on with it.’

The key, he said, has been to tell stories and provide ‘magazine style’ content for audiences with more time on their hands: ‘It’s all about contact and that, over the course of time, did lead to sales because it led to conversations.’

The gallery decided early on not to mount online exhibitions but to develop projects such as The Unseen Masterpiece, linking works by different artists who have worked with the gallery, and devising other story-based digital content. The success of this was confirmed when the exhibition by Kevin Harman, installed just before the second lockdown in December, led to sales of 12 works, most of them before the gallery reopened.

Richard Ingleby says that, while the appetite for contemporary art worldwide remains strong, collectors are now suffering from digital saturation. ‘All the art fairs have gone online and that worked for a bit, but now collectors are fed up with the idea of online browsing through 150 galleries. The bigger galleries have mostly ditched their virtual gallery spaces.’

While the gallery has weathered the storm in good shape – sales are down but, due to significantly lower overheads, profits are slightly up – the aim is to return to art fairs as travel opens up. ‘The fact is we have sold fewer art works, and because the point of our gallery is to sell the work of living artists, their lives are much more compromised. We want to get back out on the road in order to sell work and send more money to more artists.’

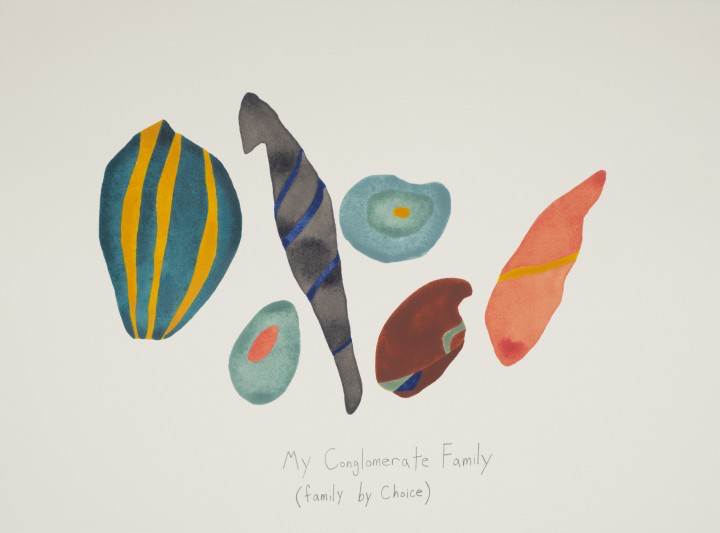

Ilana Halperin, My Conglomerate Family, 2019. Courtesy of the artist and Patricia Fleming, Glasgow 2020.

Ilana Halperin, My Conglomerate Family, 2019. Courtesy of the artist and Patricia Fleming, Glasgow 2020.

The welfare of artists is also a primary concern for Patricia Fleming, director of Glasgow-based contemporary art gallery Patricia Fleming Projects. While several of her artists are engaged in public art projects and commissions, it has been a difficult year: ‘Artists are good at diversifying, but programmes are flatlining, everyone is trying to sandwich two years of shows into 2021.’

Fleming made the difficult decision to move out of her permanent gallery space in lockdown to cut costs, and will now continue her programme in temporary exhibition spaces. She said online sales during the pandemic have not been strong. ‘The sales we made this year were to local collectors in the times when we were able to be open. People were visiting the digital site and enjoying it, but it wasn’t until they got in front of the art that they were making a commitment to buy.’

The pandemic has accentuated the gap between contemporary art galleries which are connecting with international audiences and those who rely more on local markets. Meanwhile, the pressure to maintain online engagement and content puts increasing demands on staff.

‘Moving forward, we’re going to have to accept we’ve had the rug pulled from under us just as we thought the recession might be turning a corner – and then there’s Brexit. I had to choose whether to keep my space on and lose one of my team or move out of my space. I chose to prioritise my team. It’s a struggle, but we want to be optimistic – we’re still here!’

She encouraged the Scottish Government to consider more support for Scotland-based contemporary galleries, citing those forced to close in the last decade including Doggerfisher, Sorcha Dallas and Mary Mary. ‘The Scottish Government needs to make more of the art sector. In order to have a cultural industry where people are able to make a living in a sustainable way, we need more support.

‘If they’re not going to take it seriously and build a market at home, they have to give us funding to access markets elsewhere.’