Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

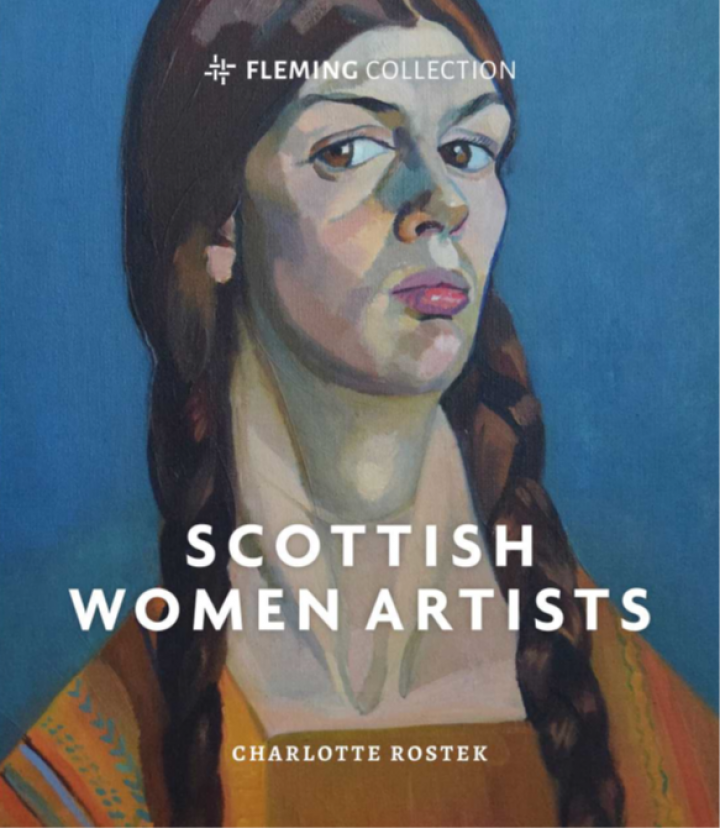

Scottish Women Artists

By Charlotte Rostek, 06.07.2022

Today women are a big part of our nation’s artistic identity. Names easily spring to mind, like Katie Paterson, Alberta Whittle and Christine Borland; leading Scottish women artists internationally recognised in the world of contemporary visual arts. Others from the recent past have become almost household names, such as Joan Eardley or Anne Redpath. But, further back, names like Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh and the Glasgow Girls have only been popularised by a determined effort since the 1980s.

My book – Scottish Women Artists – continues what we could call a retrospective corrective to the traditional, male-dominated story of Scotland’s art. This is not to inadvertently perpetuate prejudice through considering women separately, but to help make visible those often obscured, overlooked and forgotten through male- dominated writing, a male dominated art market, legislation and educational disadvantages. Women have won the future; this is about winning the past.

It’s exhilarating to see the growing popular interest as well as thriving scholarship in this field. Collaborative networks such as the Scottish Women and the Arts Research Network (SWARN), exhibitions and publications such as Glasgow Girls: Women in Art and Design 1880–1920, curated by Jude Burkhauser at Kelvingrove in 1990 and Modern Scottish Women: Painters and Sculptors 1885–1965, curated by Alice Strang in 2016 for the National Galleries of Scotland, are all superb examples of how a re-focus can bring a very fresh and much more complete perspective to our understanding of Scottish art. I also see a dynamic symmetry between the ascendancy of contemporary Scottish women artists from the 1980s onwards and the steadily growing interest in historic female artists. They each feed off each other in a way that highlights the need for legacy and context to bring broader awareness to women’s artistic identity and their place in the artistic fabric of the nation.

Writing this book has been a process of discovery. The analogy of looking up to a clear night sky came to mind – the longer you look the more stars you see and things aren’t at all as obvious as you might have thought at first glance. While male- domineered critical writing and history has ‘foregrounded’ men for the longest time, and a largely male-made educational system and society have relegated women to the shadows, there is much evidence that women in their time, and often against the odds, were incredibly active and exhibited with artworks sold at home and abroad. It was interesting to see that the process was so gradual: a good marker is that although Dorothy Carleton Smyth was appointed the first female director of Glasgow School of Art (GSA) in 1933, her unexpected death just before she could take up office meant that it was 1999 before a first woman was to occupy this important role.

Yet it is worth spelling out that there have been very positive male characters operating within the context of systemic inequality. I found it reassuring to see leading male characters who have been pivotal in supporting and promoting female artists, not because they were women but because they were good artists. A few make an appearance in the book including Peter ‘Abbe’ Grant who helped Katharine Read to obtain commissions from the Italian nobility; Francis Newbery, who alongside his wife Jessie, revolutionised GSA into one of the most progressive co- educational institutions; right up to the Fleming Collection itself which collected Scottish work by women from the 1960s onwards.

Selecting which artists to include in the book presented the greatest challenge. The brief was that 60% of the Scottish women artists should be represented in the Fleming Collection. Identifying the other 40% was dictated by the book’s overall purpose: to provide a broad overview for readers who do not necessarily know anything about Scottish women artists. There were many artists who I would have liked to include or expand on; in some cases they were at least given a name check, in others they will have to await a future project.

I approached the project quite methodically, dividing my time into phases for research, writing, revision and editing.I created thematic folders and files for nearly 80 artists and pulled together the research in tables of data listing exhibitions, key works and artistic partnerships. My laptop was creaking under the weight of the material! The book was not meant to be a catalogue, but a story with a flow. Choosing to do this chronologically made me realise quickly that not all the artists could be packed into a straight line: there are cross-cutting connections which ignore the neat categories of style, geography, schools and, for example, artists with very long lives who continue to develop artistically reaching into our own time. Where do you place them? Another challenge was to switch off and move on. I had to be ruthlessly concise.

If I were to revisit the book in, say, 20 years’ time, the acknowledged canon of female Scottish artists will have grown, and it might have changed too. As research in this field is ever more vigorous, we will be able to choose from an even greater pool. Art history is a story of survival; of those who have made it into the books, catalogues, private and public collections, public space and the internet. Through claiming the stage exclusively for Scottish women artists in the shape of books and exhibitions, and weaving a thread across the centuries, we are able to acknowledge a tradition, create context, and confirm their existence and enduring legacy.

Charlotte Rostek is an art and heritage curator, lecturer and writer, currently working as project consultant at Dalkeith Palace, Midlothian. Her book, Scottish Women Artists, is available to purchase through the Scottish Gallery.

The Fleming Collection's exhibition, Scottish Women Artists: Transforming Tradition at The Sainsbury Centre is showing until the 4th September 2022.