Scottish Art News

Latest news

Magazine

News & Press

Publications

Night Fever: Designing Club Culture

By Neil Cooper, 10.05.2021

Open Up

Now is an interesting time for V&A Dundee to be opening its doors for the first time in months for this super-club size historical overview of life after dark and the designs that have become key signifiers of club culture’s evolution. With venues still unable to open because of social distancing regulations caused by the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, plague year lockdowns have achieved what encroaching gentrification couldn’t manage.

This gives Night Fever an extra frisson that reflects some of the illegal rave rebellion that has grown throughout the last year prior to this access-all-areas exhibition. Seen in this context, Night Fever’s half-century display of collective memory is itself enough to set assorted synapses twitching with a mix of nostalgic solidarity and yearning.

A version of the show was first seen at the Vitra Design Museum in 2018 in association with ADAM Design Museum Brussels (and, interestingly, Hugo Boss). This makes for an understandable focus on assorted European emporiums, though this Dundee remix attempts to expand and localise the experience.

Before that, we whizz through images of decade-spanning future thinking hangouts, from Space Electronic in Florence to Berlin’s Tresor. Space Electronic was a multi media arts lab opened in 1969 by design collective Gruppo 9999. The group drew inspiration from the New York based Electric Circus, which opened two years earlier, and which also features in Night Fever. Tresor was the newly unified Berlin’s first techno club. Opening in 1991, its original uber-cool home was literally underground in an abandoned bank vault.

While Space Electronic and Tresor are still running, there are images here too of such voguish swinging sixties follies as the self-explanatory Yellow Submarine in Munich, Le Drug in Montreal, and Cerebrum in New York.

An evening at the Space Electronic, Florence, 1971. Courtesy V&A Dundee.

An evening at the Space Electronic, Florence, 1971. Courtesy V&A Dundee.

‘If your name’s not down, you’re not coming in!…’

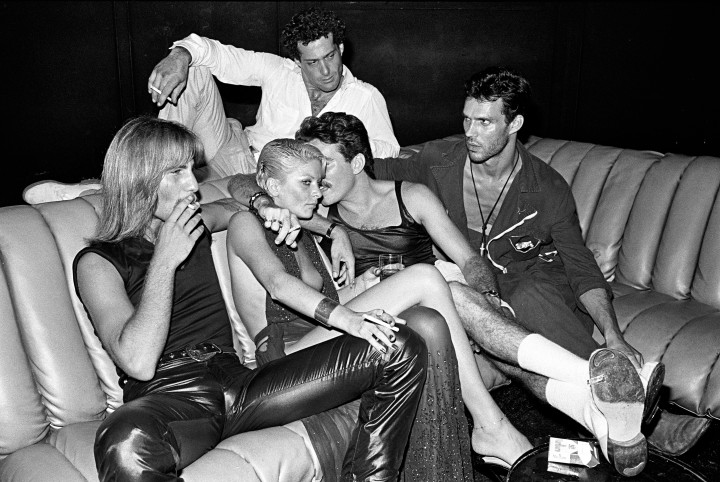

The next generation of an infinitely more rarified New York nightlife is shown off in images of Studio 54. This was the much-mythologised 1970s hedonists playground, where the likes of Andy Warhol rubbed shoulders with the post-punk new wave who really wanted to be part of his Factory a decade before.

Studio 54’s door policy was so legendarily selective that it inspired Nile Rodgers and Bernard Edwards of Chic, angry after being refused entry on New Year’s Eve 1977 following an invitation from Grace Jones, to go home and jam out a new number. While the song’s original refrain of ‘Fuck Off!’ was aimed squarely at the club’s doormen, renamed 'Le Freak', the song is arguably Studio 54’s greatest legacy.

Rodgers and Edwards’ knockback was akin to the experience of a million misfits in the 1970s and 1980s, when smart-but-casual, no-trainers door policies in the UK left anyone of remotely unorthodox appearance out in the cold. The evolution to something infinitely more dressed down is marked in the clips of late night TV show The Hit Man and Her shown in Jeremy Deller’s film, Everybody in the Place: An Incomplete History of Britain 1984-1992 (2018). Running from 1988 to 1992, The Hit Man and Her was broadcast live after midnight from various UK nitespots, and focused on showing footage of real life clubbers at play.

Along with Mark Leckey’s film, Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore (1999), and Vinca Petersen’s ten-year visual diary, A Life of Subversive Joy (2019), Deller’s hour-long film is one of the best things on show in Night Fever. First seen at the Modern Institute in Glasgow, Everybody in the Place shows Deller talking to a class of teenagers. Through archive film footage, he puts club culture in a social and political context, as mass unemployment ravaged working class communities in the 1980s as the factories that provided their livelihood were closed down. A new burst of collective energy that rose up from the debris, however, saw the dole queue generation occupy these now derelict spaces with a reinvigorated form of community by way of the warehouse party scene.

Guests in Conversation on a Sofa, Studio 54, New York, 1979. Courtesy V&A Dundee.

Guests in Conversation on a Sofa, Studio 54, New York, 1979. Courtesy V&A Dundee.

Staying Alive

Given the exhibition’s title, there is the inevitable nod to John Travolta and his appearance in John Badham and Robert Stigwood’s 1977 film, Saturday Night Fever. In the film, Travolta played Tony Manero, a blue collar Italian American Brooklynite, who found salvation ripping up the floor in heroically choreographed displays down at his local basement dive. For all this scenario existed in the same city as Studio 54, in ethos it was a million miles away.

Travolta’s image may have become a winkingly self-parodic cliché, but Saturday Night Fever had a lot more going on than its tight-trousered Bee Gees soundtrack suggested. The film was loosely based on Tribal Rites of the New Saturday Night, a piece of fictionalised reportage by British rock journalist Nik Cohn that appeared in a 1976 edition of New York Magazine. Like its inspiration, the film’s gritty depiction of working class aspiration struck a chord, taking disco into the mainstream, and turning on a million medallion men to don snug-fitting white suits and hit the dancefloor.

Like the black and gay communities that found similar senses of belonging, the working class roots of club culture in the UK at least are a vital part of its social and political history as much as its musical and visual legacy. As well as being at the heart of Deller’s Everybody in the Place, such a narrative is crucial to both Leckey and Petersen’s work.

Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore is Leckey’s willfully old-school fifteen-minute montage, that moves from Tony Palmer’s much seen film of Northern Soul dancers at Wigan Casino to mainly found VHS footage of assorted rave-age tearaways having it large. Those in the film’s later segments are dressed in the sort of expensive street-smart clobber that only a few years earlier would have seen them refused entry at every club in town.

Leckey’s film also makes explicit the umbilical weekender-centric links between the Northern Soul scene and rave culture, both of which, incidentally, have strong scenes in Dundee.

Petersen, meanwhile, epitomises the life-changing epiphanies to come out of club culture by way of A Life of Subversive Joy. This 23-metre installation utilises 600 photographs and assorted ephemera to chart her very personal trip. This sees her move from pure-pleasure-seeking teenage raver to traveling the world with assorted sound systems as part of the free party scene before becoming involved in various humanitarian projects. Spread out along a wall of the gallery, Petersen’s scrapbook style approach documents a much bigger rites-of-passage that transformed an entire generation.

Palladium, New York, 1985. Courtesy V&A Dundee.

Palladium, New York, 1985. Courtesy V&A Dundee.

Mad For It!

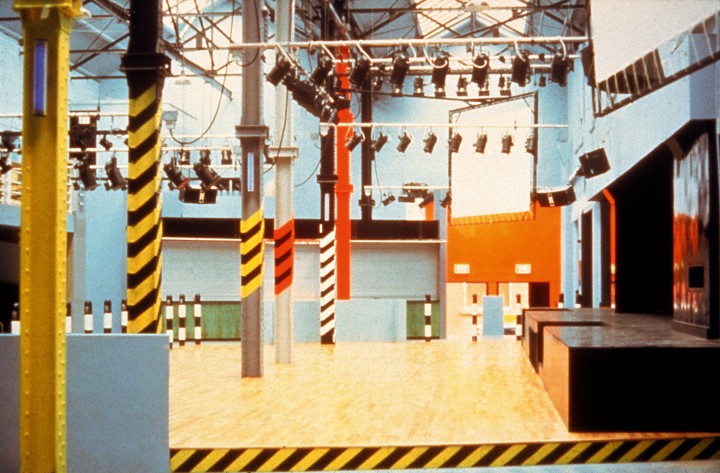

A similar sense of working class emancipation was at the heart of The Hacienda. Built in an old yacht showroom, Factory Records’ Ben Kelly designed industrial styled fun palace opened in 1982, and was inspired by New York nightclubs such as Hurrah and Danceteria. It took its name from a line in Situationist inspired French theorist Ivan Chtcheglov’s 1953 manifesto, Formula for a New Urbanism, which stated how ‘the hacienda must be built’.

The club’s early money-losing years as a gig venue were undermined even more by rubbish acoustics, a draughty interior and a stage perceived to have been built in the wrong place. All of which was in keeping with the shambolically utopian spirit of Factory’s previous venture, a night at the Hulme based Russell Club simply called The Factory. This became immortalised after Peter Saville’s immaculately designed poster for the opening night was delivered after the gig had finished.

Saville’s poster sits in Night Fever alongside a bollard and a brick from The Hacienda, which went on to help reinvent nightlife as we now know it. As Madchester turned to Gunchester, alas, the club closed in 1997 after losing its entertainment licence, and was eventually demolished. A block of flats called Hacienda Apartments was subsequently built on the site. One way or another, it seems, Chtcheglov got his wish.

Interior view of Haçienda, Manchester. Courtesy V&A Dundee.

Interior view of Haçienda, Manchester. Courtesy V&A Dundee.

One More Tune!

Currently under threat from developers is Glasgow’s Sub Club, which also features in Night Fever. The city centre venue opened in 1987 in a space given extra street cred by its checkered past as a 1940s speakeasy where Louis Armstrong once played. It is probably best known today for Optimo, the Sunday night counter cultural institution that brought Glasgow’s DIY art and music crowds into the same room.

Sub Club is a stone’s throw from where The Arches used to be. The Arches was a multi-art form venue created in a cavernous interior in old railway sidings next to Glasgow’s Central Station. After opening in 1991, initially as a theatre space, as its programme expanded, the venue’s club nights became its bread and butter, so it became akin to a Glasgow version of Space Electronic. In 2015, alas, The Arches was forced to close after Glasgow Licensing Board turned down a late licence request on advice of Police Scotland.

One section of Night Fever is called The First Big Weekend, after Arab Strap’s debut 1996 single that referenced the venue where Kieran Hurley’s rave based solo play, Beats, would premiere prior to it being adapted into a successful film.

There are more than enough stories like this to support stand-alone exhibitions for individual clubs. If it ever happened, likely candidates might include the likes of Thunderball, Going Places and other 1980s and 1990s Edinburgh nights co-promoted by Fred Deakin. Deakin’s nights were architectural interventions as much as club nights, reimagining the interiors of old cinemas and other spaces, with a memorable late ‘80s edition of Devil Mountain taking over the Fruitmarket Gallery.

Deakin’s distinctive ticket and poster designs gave each night a striking visual identity before he went on to music success with Nick Franglen as Lemon Jelly, whose gigs similarly became club-like environments. Highlighting some of that in the context of Deakin’s later tenure as Professor of Digital Arts at the University of the Arts London would work a treat.

But even Night Fever’s guest list can’t house all that. For now, it’s worth making the most of these physical invocations of the most willfully transient of artforms. As social sculpture and collective euphoria combine for what hopefully isn’t a last gasp hurrah, best keep the faith, and rave on.

Vinca Petersen, A Life of Subversive Joy [install shot], 2019. Image: Mick McGurk. Courtesy V&A Dundee.

Vinca Petersen, A Life of Subversive Joy [install shot], 2019. Image: Mick McGurk. Courtesy V&A Dundee.

Night Fever: Designing Club Culture runs at V&A Dundee until January 9th 2022